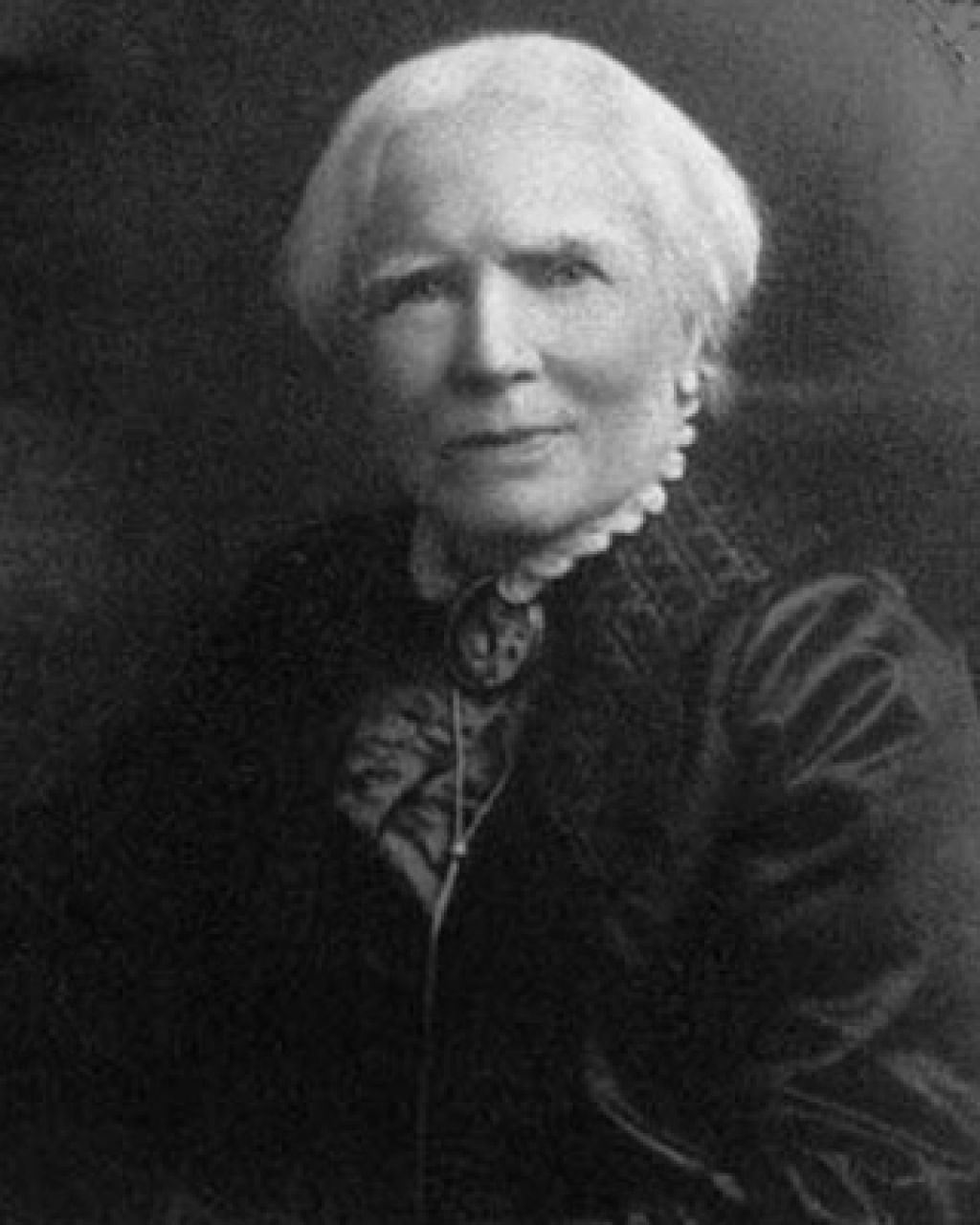

I thought a post on the early history of bookmobiles would be of interest to our readers. I quickly found when beginning my research a couple of weeks ago, however, that it is a longer and more complex history than I ever thought. After digging and digging (and digging!) I decided that my favorite aspect of this history is the role that progressive women played in the establishment of mobile libraries to serve rural families in the early 1900s. One of these women was Mary Titcomb, a woman who left a legacy of books, community service, and is credited with being the inventor of the bookmobile.

A pioneering librarian

Born in 1852, Mary Titcomb came from a family full of people who loved learning and education. Her father was so concerned that his sons receive a better education than he did that the family moved from Farmington, New Hampshire to Exeter, New Hampshire so they could attend the well-respected Phillips Exeter Academy. As the story goes, Mary and her sister also had a deep desire for education and would be enrolled in and graduate from Robinson Female Seminary, also in Exeter.

Mary didn’t just want an education, she wanted a career and to dedicate herself to something great. When she saw an advertisement for a library internship in a church program, she had found her cause. I love thinking of her being so excited about the ad as I know the feeling of hearing about something that automatically lights you up in that way. After her internship, she took a job as a librarian in Vermont, where she would happily remain for 12 years.

Mary entered the field of library work at just the right time to make a flourishing career out of it despite formal education in the topic. A few years prior (she began library work in the 1870s) and a professional occupation would have been closed to her as a woman. A few years later, the role would require advanced degrees and certifications, thanks to the pioneering efforts of Melvil Duey himself to professionalize library work.

This lack of training per the Dewey system would hinder Mary’s efforts, but not enough to derail her. In 1893 she applied to work as a librarian at the Woman’s Building Library at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and was denied as Dewey felt she wasn’t established enough. This would go on to be a famous story of early rejection in the career of someone who would become famous in their field.

“The book goes to the man, not waiting for the man to come to the book.”

After serving her local Vermont community for 12 years Mary took a role as a librarian at the Washington County Library in Washington County, Maryland. The library was only the second county library in the United States and had a lot of potential for shaping the world of libraries into how we know it today.

One of the goals that Mary and the board shared was making books more accessible to rural citizens. “Book stations” were set up in community areas such as general stores and post offices, growing from 22 stations within two years of Mary’s arrival to 66 stations within five years. She was also known for setting up a separate children’s room in the library and creating colorful bulletin boards to promote reading and certain books, something that I am sure everyone associates with libraries still today.

Although the reach of the library had expanded, Mary still noticed that it was primarily townspeople who were using it, not people from the greater county. Given the lifestyle and demands of working land that these people were faced with, Mary decided that the books would need to go to them and not the other way around.

And with that, funding was secured to build and begin operating the first mobile library.

The bookmobile set out on its first trip in 1905, pulled originally by horse and buggy and driven by Joshua Thomas, a man from the rural area, and a janitor at the library. It is said that Mary’s instructions included allowing families ample time to browse the book selection and to enjoy the arrival of the library on wheels. Thomas reveled in the role and would refer to himself as “The Book Prophet.” The project was so beloved that when the cart was destroyed by a train in 1912 funding allowed it to be replaced by a motorized cart.

Legacy

Mary’s ingenuity had a ripple effect around the world and saw her career skyrocket. In 1914 she was elected Vice President of the American Library Association, the very organization that Melvil Dewey himself had helped found. Apparently, he had been forced to leave the organization years earlier due to repeated allegations of sexual harassment.

Additionally, the bookmobile movement would spread, with carts springing up not only around the country but around the world. They would even become an important part of the morale efforts in World War I, with mobile units being used to bring books to soldiers around Europe.

Mary’s colleagues had once described her as “alert in manner, effective in results, her belief in whatever she undertakes stimulates all about her into hardy cooperation. And this everywhere is the secret to her success.” This glowing review certainly makes sense for someone who started a book revolution.

Oddly, when Mary passed in 1932 she was buried next to her sister in an unmarked grave in Sleepy Hallow Cemetry. Even though she was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame in 1990, the graves would remain that way until 2015 when author Sharlee Glenn raised funds to have headstones created and placed for both women.

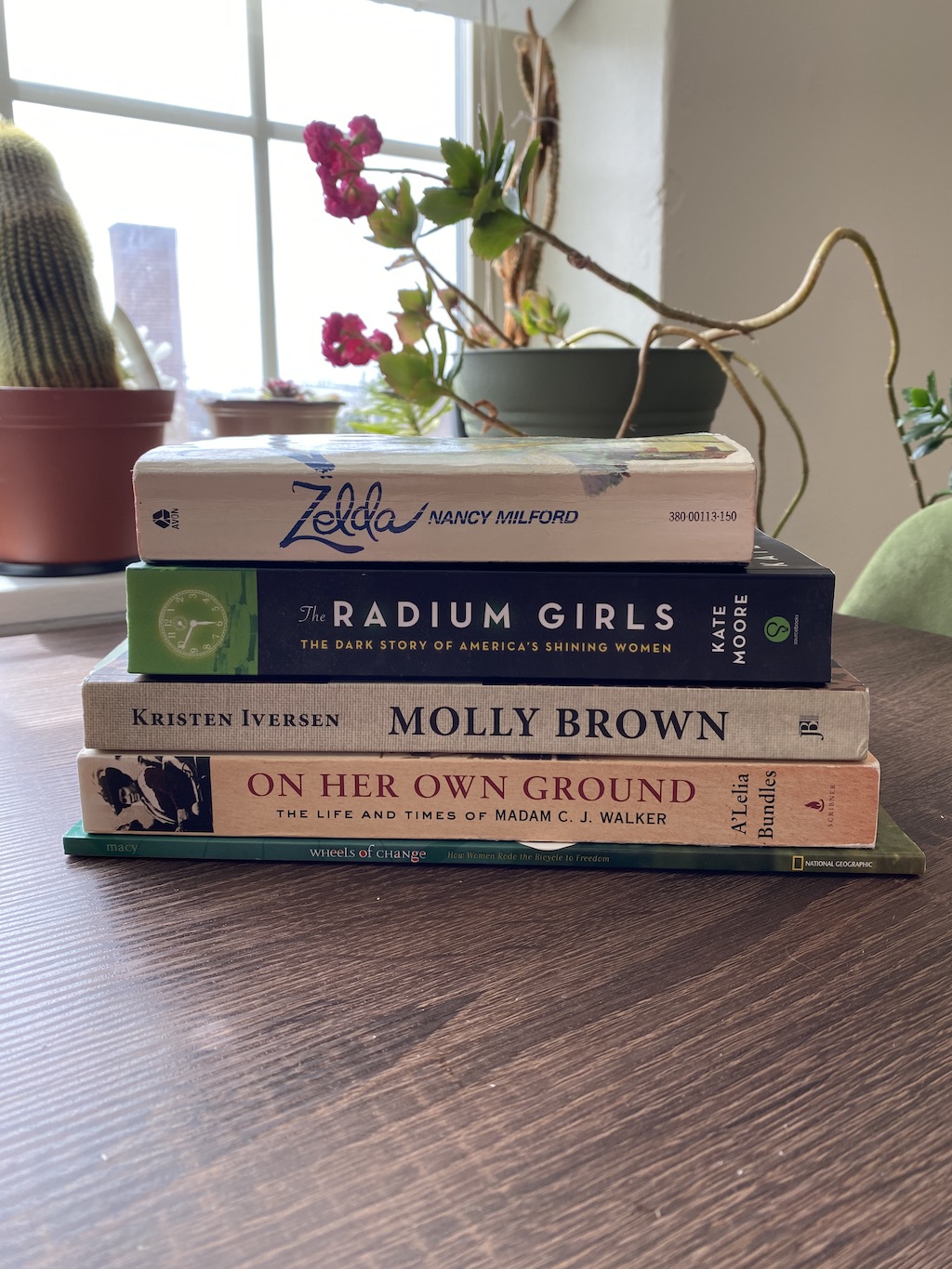

I am so glad that Mary Titcomb is remembered still today! Make sure to share her story with the book lovers in your life and if you’d like to read more about her check out these resources:

Library on Wheels: Mary Lemist Titcomb and America’s First Bookmobile

What’s Her Name Podcast: The Book Missionary: Mary Lemist Titcomb

More women’s history fun:

5 facts about Margaret Tobin Brown (aka The Unsinkable Molly Brown)

Godey’s Lady’s Book: What You Don’t Know

Irene Castle: Flapper Era’s Best Dressed

Hi, Janice, I just found your blog, and love it. Mary was probably a very distant cousin to me, as I have New England Titcombs in my family tree. I think I would love to be a librarian, but am not going back to school again. LOL

Thank you for reading, Saundra! I am so glad you enjoy the blog.

Perfect story for Womens’ History Month! Thanks, Janice, for your dedication in bringing history to life for the rest of us. I look forward to your stories along with each beautiful Recollections e-mail post. A feast for the eyes and the heart.