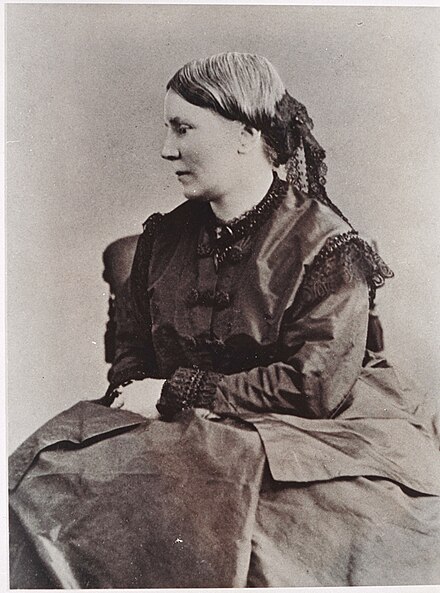

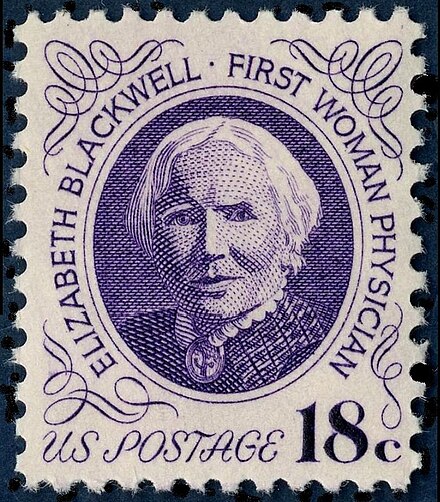

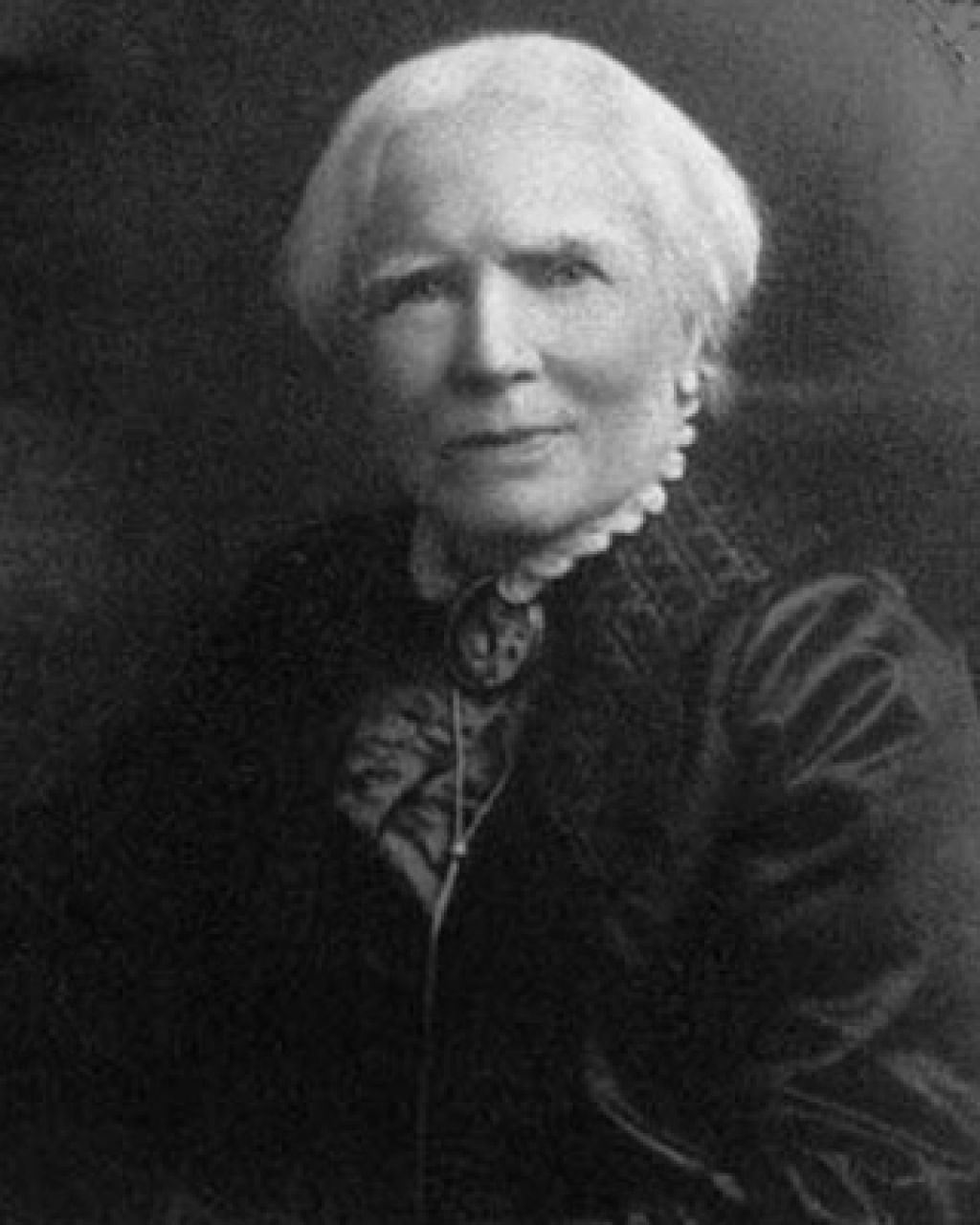

A lot of women made enormous strides in the 19th century. One woman carved the way for others in two different countries and left a legacy still honored today. Are you familiar with Elizabeth Blackwell? Born in 1821, she is recognized as the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States and the first woman Medical Register of the General Medical Council for the United Kingdom. She was also one of the most well-respected, honored, and influential social reformers of her time.

Here are five facts about Elizabeth Blackwell that will leave you wanting to learn more.

Do you love women’s history? Sign up for our newsletter so you don’t miss a thing.

Let’s talk and women’s rights!

It may seem obvious that a woman who would be such a pioneer as to be the first to earn a medical degree would be concerned about women’s rights. Ms. Blackwell took this concern to an unprecedented level.

Making receiving and giving medical aid easier for women was a life goal for Elizabeth. It is said that her initial reason for pursuing training was that while dying, a female friend had mentioned how much more comforting it would have been to have been treated by a female doctor. With that, legend has it, she set off to make that happen for future women.

Elizabeth broke into the field decades before it would be common for women to do so. Remarkably, she was accepted into Geneva Medical College in 1847 after being denied entry to many others. She was about to get a crash course in what a woman was up against in the medical field. The all-male student body voted to accept her, but as a sort of joke. They wouldn’t make it fun for her, a theme that would be prominent throughout her entire career.

One of the top students in her class, Elizabeth would pursue advanced degrees from her birth country, England (her family had migrated to Ohio in 1837). When she returned to America in 1851 she saw that female physicians and patients alike were having difficulties; the physicians with reaching the public due to discrimination and the patients with receiving adequate care.

Elizabeth sought to change this. She would successfully open and help run the following:

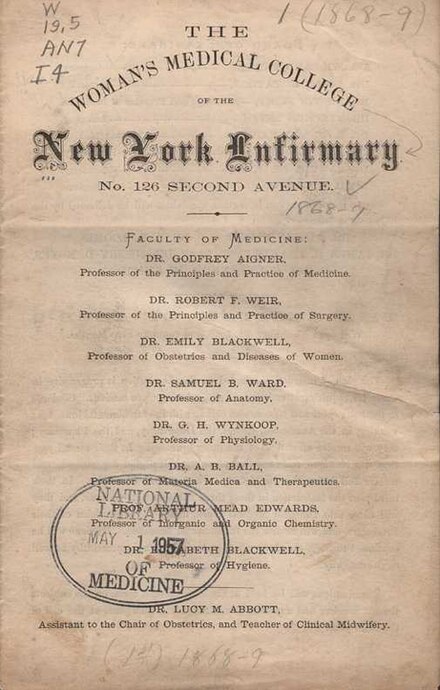

-1851: A clinic to serve poor women (staffed by female physicians)

-1857: New York Infirmary for Women and Children

-1868: A medical college to support females trying to enter the field

She was partially blind for most of her career

Elizabeth had originally wanted to be a surgeon. She had plans to receive training in this area when she went back to Europe in 1849, but she was only permitted to work as a midwife, and then an obstetrician. It was in this role that her career would be altered forever from a practicing doctor to thought leader.

While treating an infant inflicted with a severe case of conjunctivitis (believed now to have likely been chlamydia contracted during birth), Elizabeth accidentally squirted some contaminated fluid into her own eye. The horrible infection would lead to her losing sight entirely on that side.

I assumed that this setback would have defined a lot more of Elizabeth’s career and identity to a certain extent. However, out of the facts about her life, her blindness was the thing I located the least amount of information on.

Progress was a family affair

It is fascinating to me how many of the thought leaders/change makers of the 19th century came from families with other influential people. That’s probably a good topic for an upcoming post!

The Blackwells were one of these families. Parents Samuel and Hanna were free thinkers and encouraged their children to do the same. They were staunch abolitionists and experimented with various unorthodox parenting techniques. The family had four girls and five boys, all educated rigorously with private tutors at home.

Being brought up in such an egalitarian home with free-thinking parents had an enormous impact on the children and on their formative years. Many of them would become movers and shakers in the social revolution that would take place during their lifetime.

For instance:

-Eldest sister Anna: A successful European journalist and social activist

-Middle son Samuel: A prominent abolitionist and husband of Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first American woman ordained as a Protestant minister and well-known public speaker on women’s rights.

-Middle son Henry: One of the founding members of the Republican Party and the American Woman Suffrage Association. Married to none other than Lucy Stone herself.

-Second youngest daughter Emily: The second woman in the US to earn a medical degree and a famous woman’s rights activist.

Now that’s what I call a power family!

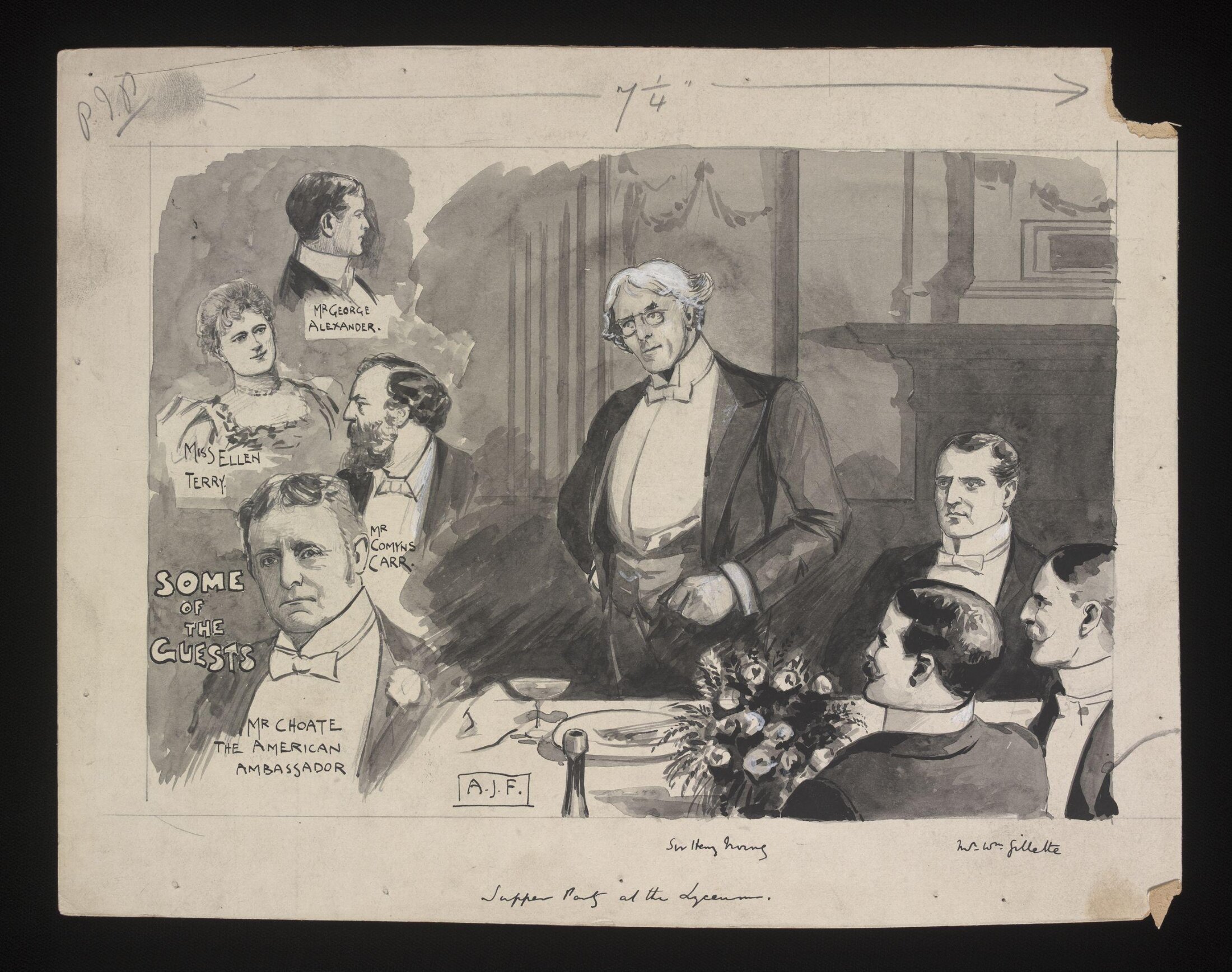

Elizabeth at The Dinner Party

I have been a huge fan of Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” since my early college days. I’ve even had the honor of viewing it in person and plan to do so again. If Elizabeth’s life sounds intriguing you will be glad to know that of the only 39 place settings in the elaborate ceramic and textile installation one of them belongs to her.

The exhibit is now permanently housed at the Brooklyn Art Museum. In part, her entry on the website reads:

Elizabeth Blackwell’s place setting is a metaphor for both her triumphs and her difficulties in the field of medicine. The plate is comprised of twisting, brightly colored forms that swirl toward a central “black well,” a visual pun on the doctor’s name. Like the new opportunities for women that arose out of Blackwell’s efforts, the plate’s curling color bands seem to be lifting off and growing out of their base.

The illuminated letter “E” on the front of the runner is embroidered as a stethoscope, a medical symbol referencing Elizabeth Blackwell as the first female doctor in the U.S.

Keeping her company around the table is Mary Wollstonecraft, Emily Dickinson, Sacajawea, and others. Imagine being at that dinner party!

A continued legacy

Elizabeth paved the way for so many women to enter a field that improves the quality of life for each member of society and that is often the determining factor of whether or not a person has life at all. She was beloved in her lifetime and this post doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of of influence. Her biography may be the next one I read!

Luckily her hard work and impact are remembered today. Each year the American Medical Women’s Association grants an award in her name. Recognizing the way that she changed all of society for the better, Hobart and William Smith Colleges awards an annual award in her name to female students who have given “outstanding service to humankind.”

And guess what? Hobart and William Smith Colleges trace their origins back to Geneva Medical College, the very same that Elizabeth had to overcome studying to become the world-changing physician she was.

Kilmun, Scotland

Are you inspired by the stories of courageous women from the past? Continue reading:

Five fun facts about Sarah Bernhardt

Leave A Comment