First, Charles Dana Gibson brought us the Gibson Girl. Then, after Gibson’s retirement from illustrating, Harrison Fisher arrived on the scene. His Fisher Girl “redefined the American ideal of feminine beauty” during the first quarter of the 20th century.

Who was Harrison Fisher?

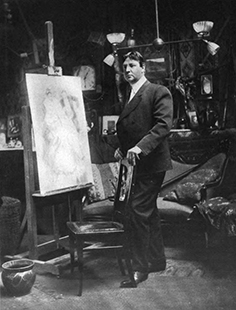

Harrison Fisher was born to be an artist. His father, Hugo Antoine Fisher, was an artist as was his paternal grandfather, Felix Xavier Fisher.

Felix, his wife Mary, and Hugo and his wife Addie, immigrated from Prague, Bohemia, Austria (now part of the Czech Republic) sometime during the early 1870s. They settled as one household in Brooklyn, New York.

The 1880 federal census shows that the family also consisted of two sons; Harrison, and Hugo. Harrison was born on July 27, 1877. Both boys would grow up to be successful artists. Hugo Melville Fisher was known for his Pacific coastal landscapes and Parisian street scenes.

Moving west and moving up

The family moved to Alameda, California in 1887. This allowed Harrison to receive formal training during his teens at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in San Francisco. His goal was to be an illustrator and commercial artist.

One of Harrison’s classes was instructed by Amadee Joullin who was known for paintings of the Aztec people. Harrison submitted one of his drawings to the United States Playing Card Company in 1894. They liked it enough to publish it on the back of decks of playing cards. The same year, one of his political cartoons appeared on the back cover of Judge, a humor magazine.

At age 17, he was hired by the Morning Call (later known as the San Francisco Call). He moved to the San Francisco Examiner where his talent was recognized by the publisher, William Randolph Hearst. It wasn’t long before Harrison Fisher was back in New York working for a new Hearst acquisition, the New York Journal.

Fisher’s New York adventure

Harrison wouldn’t spend too much time at the Journal before moving on to work for one of the nation’s first humor magazines, Puck. In 1898, his work started appearing on the covers of such notable publications as The Saturday Evening Post (1898), The Woman’s Home Companion (1901), and The Ladies’ Home Journal (1903).

Doors were opening and in 1906 he was hired as an illustrator for The American Magazine, a Hearst publication that was a Sunday newspaper supplement. This lead to covers for Colliers (1907), and Cosmopolitan (1907). He was now a household name.

Harrison maintained a relationship with Cosmopolitan for 22 years. His illustrations appeared on the cover 293 times, which was almost every issue from 1913 until his death in 1934. He also illustrated many covers for other publications including Nash’s Magazine (112), The Saturday Evening Post (110), and The Ladies’ Home Journal (37).

Branching out

With his distinct illustrations becoming more popular, Harrison signed an agreement with Charles Scribner & Sons in 1907. The publisher created a large coffee table edition of glossy bookplates that showcased his illustrations’ ethereal style and the artist’s immense talent. This was the first of fifteen books that featured his artwork paired with specially selected poetry.

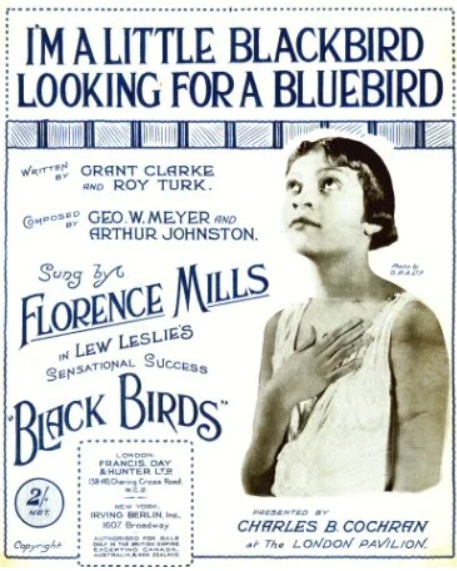

Because many of his illustrations were owned by the publications, they were free to exploit them. You could find Harrison Fisher’s illustrations on postcards and sold as prints. Cosmopolitan sold 11”x15” prints of some of his most popular illustrations. “His work was so popular in his day that his images were reproduced on postcards, calendars, candy tins, sheet music, novelty mirrors, and tape measures.”

Harrison Fisher also provided original illustrations and cover art for novels of the day. His work appeared on the covers of books by Percy Brebner, George Barr McCutcheon, Harold MacGrath, and Katherine Thurston. Other freelance work included illustrations for Armour’s beef and Pond’s soap.

In addition to illustrations, Harrison painted portraits of many celebrities of the day including the actress Marion Davies (and Hearst’s mistress), F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda, and Billie Burke (Glinda, the Good Witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz).

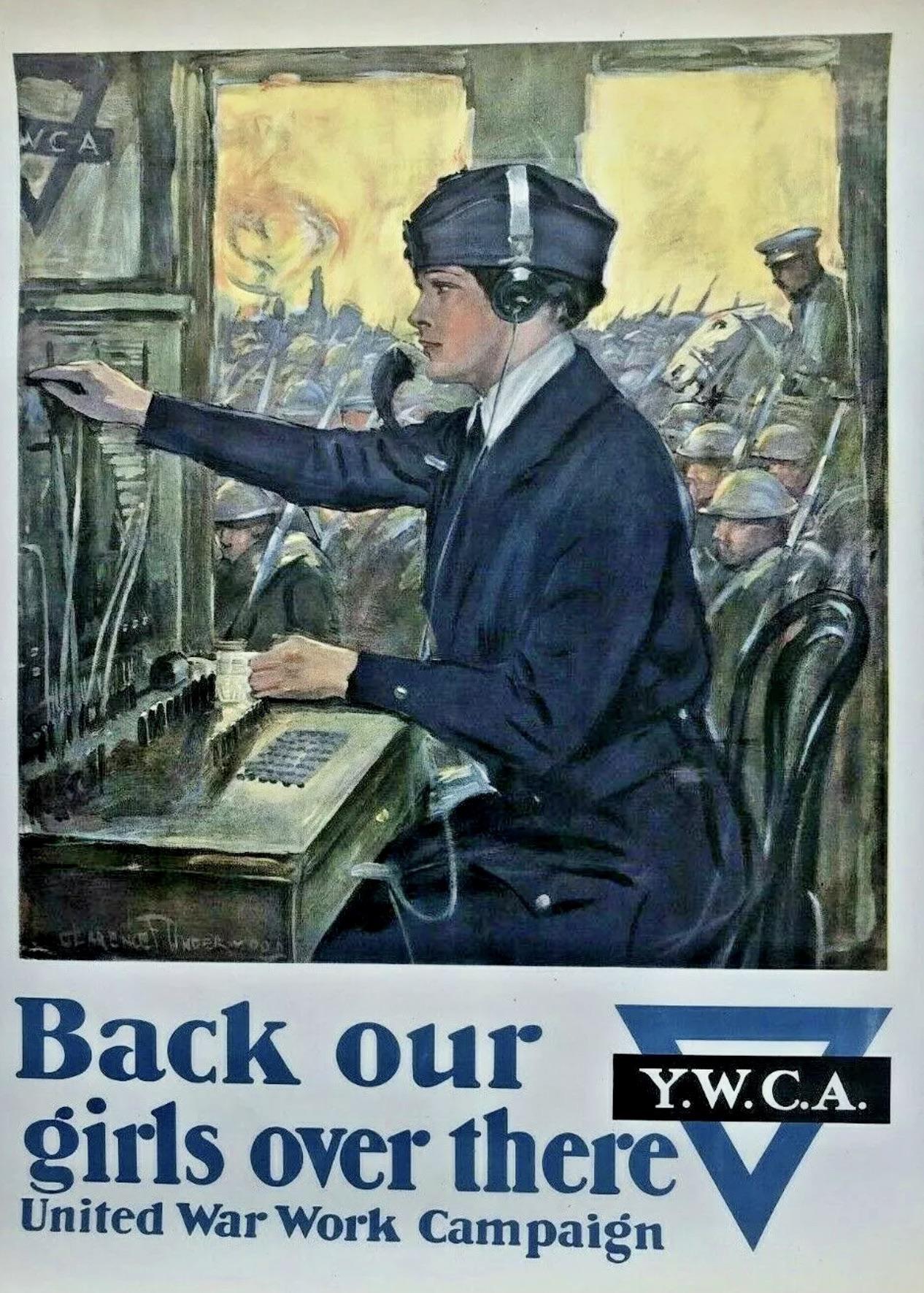

He answered the call for the cause during World War I. Four of his illustrations were used on posters that publicized the United States’ war effort. They appeared on buses and in windows. Three posters were made for the Red Cross.

The Father of 1,000 Girls

TheCosmopolitan Magazine gave him that nickname in 1910. “Later in his life, Fisher claimed to have painted no fewer than 15,000 women.”

One of his models was Rita Rasmussen. She was found during a national model search for ‘the real American beauty.’ She was dubbed the ‘Girl of the Golden West.’ He used her in two illustrations, Sunbonnet Girl and Maud Muller (or Bewitching Maiden). Other models included Olive Thomas, Lucy Miller, Margery, Allwork, and Dorothy Gibson (no relation to Charles).

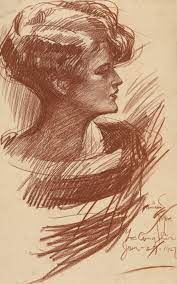

Harrison Fisher’s Girls

Success Magazine published an article about Harrison Fisher’s girls in 1908 that fanned the flames of their popularity. “Since Charles Dana Gibson has given up his pen and in work for oil paintings, Mr. Fisher has become his natural and popular successor.”

What Harrison Fisher created was an illusion of an ideal that didn’t exist in real life but were media-ready. What he did is not unlike what we do today with an app that changes a photo to make it ‘social media-ready.’

The jawline is a steeper angle than found in the human anatomy. Other characteristics include wide-spaced eyes and short noses. “His illustrations are a kinder, softer representation of substance.” He was a master of watercolor and used this medium to his advantage to create this illusion.

Harrison’s illustrations depicted an idealized beauty, but his women were healthy, intelligent, and hardworking. They were painted as athletes, scholars, brides, mothers, and sometimes as the coy tease.

The World’s Greatest Artist

During the 1920s, Cosmopolitan Magazine called him ‘The World’s Greatest Artist’ and described his work:

“There is an underlying ideal that dominates his paintings. His ideal type has come to be regarded as the type of American beauty: girls, young with the youth of a new country, strong with the vitality of buoyant good health, fresh with clear-eyed brightness, athletic, cheerful, sympathetic, and beautiful. ‘The American Girl’ is practical, adventuresome, active, and above all, attractive. No one can portray more of this attractiveness than Harrison Fisher.”

The end of an era

The man who was surrounded by beautiful women claimed he was too busy to marry. He was a bachelor when he died on January 19, 1934. His estate of more than $250,000 was left to his companion and secretary, Kate Clements. George M. Cohan delivered the eulogy at his funeral.

Harrison Fisher never valued his illustrations because they were commercially available. “After his death, a relative kept a few paintings and burned over 900 of his remaining artworks, at his request.” His remaining artwork can be seen in many museums throughout the United States. He was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1997.

Credits and more information

What’s it Worth? Harrison Fisher’s women

Harrison Fisher and the American Beauty

Love art history? Check out these posts:

Emilie Flöge: a woman to be remembered

The Gibson Girl: New Ideal for a New Century

Helen Allingham, acclaimed Victorian commercial artist and water colorist

Leave A Comment