While this week we celebrate Veterans Day to honor all who have fought in our country’s wars, it was originally established as Armistice Day in 1919 to recognize and honor those who had recently served in World War One. What was a bit overlooked then, and still sometimes now, was the widespread contributions of women in WWI. Here are some of their stories to remember this Veterans Day and the anniversary of the end of The Great War.

Women in WWI Hospitals

For the first time in the country’s history, American women could be active abroad as military nurses. In WWI, 21,498 US Army nurses and 1,476 Navy nurses cared for wounded soldiers. Women also volunteered to work in hospitals operated by the Red Cross. By 1918, 3000 American nurses worked in Red Cross hospitals in France. The Red Cross Motor Corps enabled women who knew how to drive to use ambulances to transport patients, supplies, and personnel.

Many female physicians were rejected from the US Army Medical Corps and so the Medical Women’s National Association raised funds to send these physicians to hospitals operated by the Red Cross. Women were often in danger as they cared for wounded and diseased soldiers. Sophie Gran, an anesthetist, described one experience: “I had just given this poor boy anesthesia when a bomb hit. We were supposed to hit the floor, but he was out and didn’t know what was going on. I took a tray and put it over our heads. It wasn’t because I was brave. I was just scared.” More soldiers would have died during WWI if it were not for these women nursing them back to health.

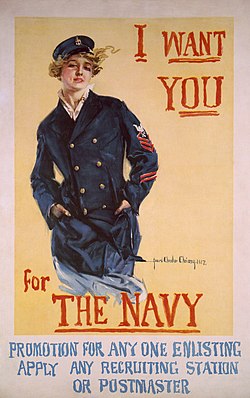

Yeomen: American Women in the Military

In WWI, American women could serve in the Navy as Yeomen, non-commissioned officers. Twelve-thousand Yeomen served stateside to replace the men who were deployed overseas. Yeomen worked as truck drivers, translators, mechanics, munition workers, and did clerical work. They received the same pay as the men and received the same veterans’ benefits after the war. In contrast, female nurses in the Army Nurse Corps received less pay than their counterparts and didn’t have military rank or veteran status.

Female switchboard operators, called “Hello Girls”, also did not have veteran status during the war. Bi-lingual women were recruited to improve the communications between the Western front and the Allied forces. They worked close to the front lines and received physical training. President Jimmy Carter signed legislation in 1977 to honor the female switchboard officers for their bravery by recognizing their veteran status, but by that time there were few still alive.

Women Stateside

Women in WWI not serving in hospitals or in the military helped the war effort in other ways. Housewives in the U.S. signed pledge cards, pledging to “carry out the directions and advice of the Food Administrator in the conduct of the household, in so far as my circumstances permit.” Women pledged to conserve food, so troops would have more to eat. Slogans, like “food will win the war”, encouraged families to give up certain staples, like meat and wheat. Food boards offered advice to families on how to prepare meals without these staples. These efforts allowed for twice as much food to be sent to Europe in 1918.

Deployed men left jobs in factories and farms vacant. More than one million American women worked in factories during WWI to build war necessities such as engines and airplanes. Henry Ford, of Ford Motor Company

Women in WWI should be remembered for their contributions in the war effort. Their involvement also gave women more of a role in society outside of the home, which would pave the way for the women’s suffrage movement.

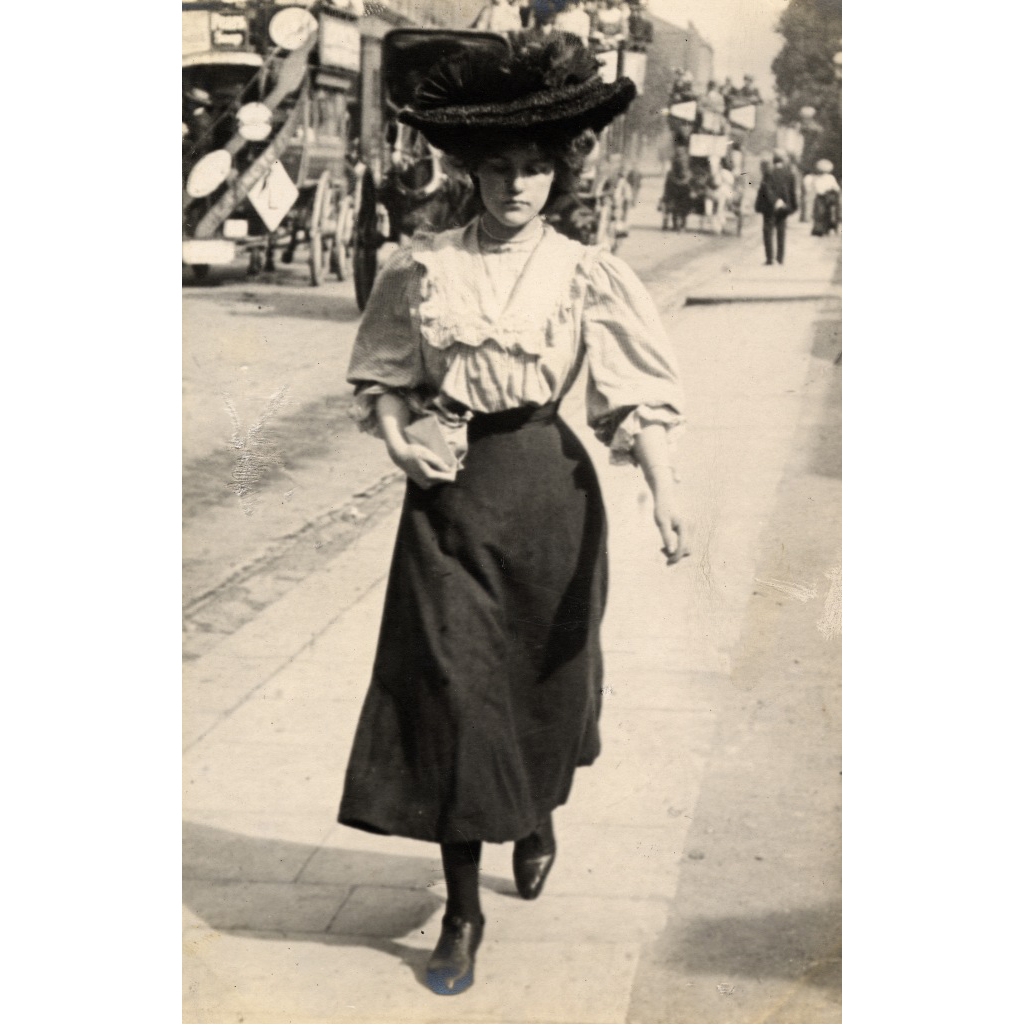

WWI was the first instance American women wore uniforms to signify their service to their country. Create your own look:

See Recollection’s WWI Nurse’s Uniform and WWI Food Conservation Uniform.

Read more about the origins of Veterans Day here.

Written by Faith Briggs – thank you!

Updated 10/21 by Janice Formichella

Women have and always will be a great service to this country. It is outstanding to see how far we have come.