Many of us know about the women’s suffrage movement, abolition, and temperance societies, but what about the dress reform movement?

Many of the most radical and audacious women involved in progressive movements of the Victorian Era could see the way that women were physically prevented from fully participating in society. Such limitations, they argued, took the form of the literal cages that women dressed in each morning. While men moved swiftly through their days and through various decision-making roles, women were weighed down by multiple dozens of pounds of clothing, were bound by whalebone corsets, and shackled by skirts that impeded certain physical movement and activity that men took for granted. The dress reform movement, or rational dress reform, sought to demonstrate to all women the possibilities that altering their clothing could present.

Today, women are as free to wear a suit and tie as they are to wear long skirts and Victorian-inspired gowns, but it wasn’t always that way. Let’s take a look at the people and dynamics that shaped the small but passionate dress reform movement and how drastically things have changed.

Libby Miller’s Bloomers

While the name Libby Miller may not ring a bell, you will no doubt have heard of her contemporary claim to fame, Bloomers. You may have also heard of her cousin and partner in crime, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Elizabeth Smith Miller (who went by Libby) was born in 1820, the child of passionate abolitionists. Her childhood home in Peterboro, New York was a favorite summer destination of Cady Stanton and was also a part of the Underground Railroad. Perhaps partially due to being raised with such progressive influences, Libby had a naturally open mind. She wrote in her journal that one day as a young married woman she was gardening and grew frustrated with her long dresses and became determined to devise a solution. Taking to her sewing kit, she designed a costume of “Turkish trousers to the ankle with a skirt reaching some four inches below the knee, were substituted for the heavy, untidy and exasperating old garment.”

Being pleased with the results, Libby was excited to show off the altered dress to Cady Stanton when they met up next. Dress reform had already become a topic of concern and conversation in progressive circles by this time, and Cady Stanton willingly adapted the Turkish trousers and short dress. Cady Stanton waxed poetically about the invention saying: “Like a captive set free from his ball and chain, I was always ready for a brisk walk through sleet and snow and rain, to climb a mountain, jump over a fence, work in the garden, and was fit for any necessary locomotion. What a sense of liberty I felt with no skirts to hold or brush ready at any moment to climb a hill-top to see the sun go down or the moon rise, with no ruffles or trails imped by the dew or soiled by the grass.”

The next woman to join the ranks was their friend Amelia Bloomer, who wrote about the convenience of the outfit in her newspaper The Lily, and thus became the namesake of the liberating trousers and skirt. However, as much as these pioneering women loved the new fashion, the rest of society was slow to accept the innovation, and the close circle of Bloomer advocates struggled to keep the trend alive, as we shall see below.

The Corset Controversy

There were few aspects of the dress reform movement that created such a controversial stir as the corset. It was a hotbed issue that divided proper society for decades during the 19th century and even threatened to pull households apart. Today, we refer to it as The Corset Controversy.

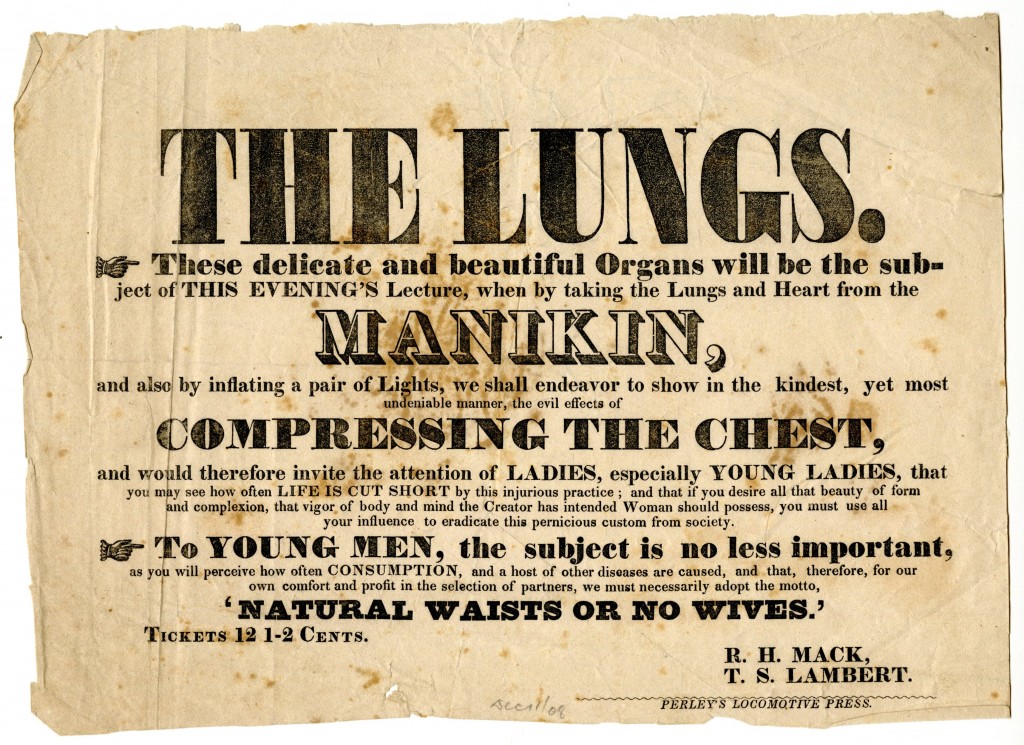

The corset was, in fact, the first item of clothing to truly raise enough eyebrows to call into question the public health concerns related to the ever-increasing extravagance of women’s clothing. While the feminist-minded were quick to jump on board, it was the medical establishment that brought the issue into public discourse. At the time it was believed that the physical consequences included compression of the lungs, disrupted digestion, decreased oxygen supply to the blood, and a less developed uterus.

Acknowledging the possible health consequences of tight lacing, dress reform activists jumped in with a philosophical angle to the argument. At times, an ideal waist was considered 17 or 18 inches (the CDC currently lists the average waist size for an American woman to be 38.7 inches). Recognizing the manner that being bound to this extent limited a woman’s ability to move freely, dress reformers likened the ubiquitousness of the corset to a type of enslavement.

While all arguments against the corset appear as rational and agreeable as can be to most of us today, it was a slow and steady fight, with most of “proper society,” even much of the women’s rights community, arguing loud and hard for the corset to be left tightly in place. Supporters, who had all been raised to wear the corset by their corset-loving mothers, passionately defended the necessity of the undergarment. Many newspapers covering the controversy included editorials from women who stated the mere enjoyment of the practice. The overall argument, however, was simply that all respectable women wore them, that tight lacing encouraged proper posture, and that it was just the way things were done.

The Bicycle

The inadvertent hero of the dress reform movement was the bicycle. The invention of the bicycle can be traced to about 1815, but it took until around 1885 for the design to evolve to the practicality of the “safety” bicycle, and when it did, female writers and adventurers were ready to sing its praises. Thus, where the suggestion of the removal of the corset failed to attract legions of women ready for liberation, the bicycle succeeded. Simply put, it was (and is) difficult to properly enjoy the use of a bicycle in the traditional dresses of the day, and as each curious rider emerged an enthusiast, less restrictive clothing was purchased to enhance the bicycling experience.

Like all feminist movements of the day, religious leaders were quick to turn to the pulpit to condemn female use of the bicycle, with the necessity for more “masculine” dress a common concern. There was even a trial run of a chainless bicycle, sold with the promise that everyday dresses could be worn given the removal of the threat of the skirt being caught while peddling.

But the bicycle as we know it today was here to stay. And while the bicycle alone could not single-handedly overpower women’s desire for fashionable clothing, it succeeded in bringing the issue of rational dress back into the mainstream, where it would remain until fashion could do the rest of the work.

Dress Reform Parlors

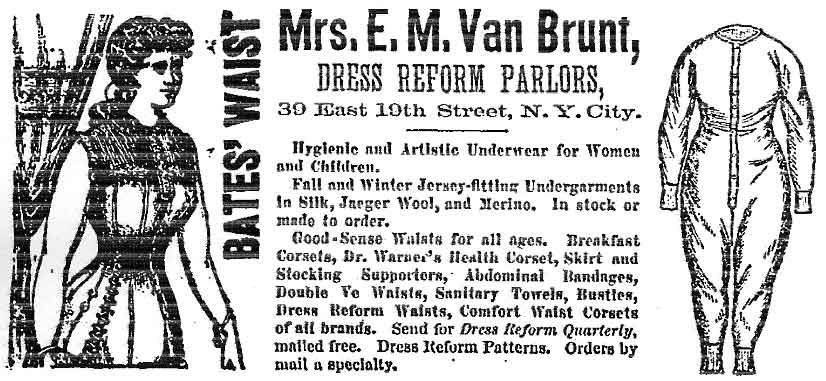

I would like to give dress reform parlors an honorable mention in the list of main players. I myself hadn’t heard of them before researching for this blog post and I am now on a mission to discover more contemporary documentation of these centers for radical convenience.

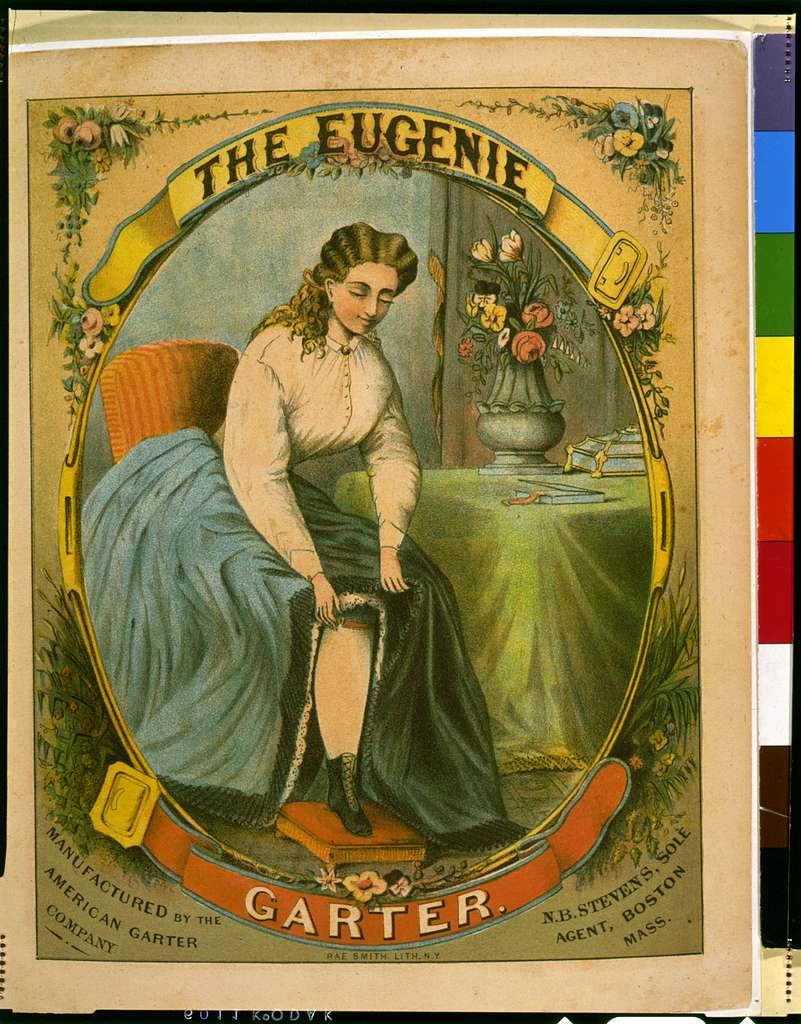

Dress reform parlors could be found in the major city centers of the various progressive movements, largely Boston and New York City (the cities I came across in my limited research into the topic). Female owned, they were storefronts where women could find the scantily produced radical wardrobe items and patterns to produce their own. One popular option in such establishments was a pattern for the “emancipation bodice,” which hung from the shoulders and enjoyed momentary interest among those wanting to wear snug bodices while avoiding the ill effects of tight lacing.

Dress reform parlors appear to have disappeared from the streets by the 1890s, but as always, I am interested to know if anyone has resources to further my study.

Lady Harberton and the Rational Dress Society

The Rational Dress Society was founded in England in 1881 for the purpose of promoting a shift in women’s clothing that would promote movement and practicality. In part, their motto read: “The Rational Dress Society protests against the introduction of any fashion in dress that either deforms the figure, impedes the movements of the body, or in any way tends to injure the health. It protests against the wearing of tightly-fitting corsets; of high-heeled shoes; of heavily-weighted skirts, as rendering healthy exercise almost impossible; and of all tie down cloaks or other garments impeding on the movements of the arms.”

Among the co-founders was Lady Frances Herberton, who was likely the most ardent “practice what you preach” member of the community. She was an equestrian and cyclist with the attitude and confidence necessary for the face of the movement.

To give you an idea of what Lady Herberton was up against, and how thick of a skin she had, consider the story for which she can credit the 15 minutes of fame she enjoyed during her lifetime. In 1899 she sued the owner of a cafe for refusing her a table at the main area of the restaurant due to the fact that she was in her “full rationals” (trousers). Interestingly, the owner of the establishment said Herberton was permitted to sit in the “bar” section of the cafe, which she found imprudent as men were occupying that area and smoking.

While the case was dismissed (the jury found that it was acceptable that the owner had offered her a seat at the bar and therefore not refused her service), it was a win for the Rational Dress Society and the Cyclists Touring Club, both of which enjoyed substantial press over the case and a huge soapbox for Lady Herberton to discuss the issue. One paper quoted her as saying: “short skirts for walking-wear will be a boon that ought to be easily attained, and once attained, cherished like Magna Carta in the British Constitution.”

The Status Quo

The most powerful actor in the many sagas of the dress reform movement was the good ol’ status quo, which reared its head at each and every step forward its participants would make.

Remember Libby Miller? While she waxed prophetically about the joys of Bloomers, she would lament later in life that her “love of beauty” had caused her to discard the outfit for the more fashionable clothing of the time. And Amelia Bloomer? Oddly, she publicly denounced her garment namesake once crinoline took mainstage, claiming that the skirt cage offered a more comfortable and practical option than the dress style for which she had adopted the trousers and short skirts.

Both women also remarked that it was challenging to withstand the ridicule they received when they wore Bloomers in public, the dynamic that most historians credit with the outfit never gaining widespread popularity or mainstream use.

Likewise, the pro-corset argument had one ally that proved to be the most powerful of all: contemporary notions of beauty. While the battle would carry on well into the 20th century, it would remain just that, a topic of debate. Even the most progressive members of the women’s movement would continue practicing tight lacing, as evidenced by an ample collection of contemporary photographs.

Indeed, nearly all dress historians agree that it was not the work of progressives that led to the abandonment of the corset and the adoption of trousers at all, but a change in fashion and circumstance. At the beginning of the second decade of the 20th century, dresses rapidly evolved toward a look that included a long, narrow bodice with much less emphasis on the waist. While corseted fashions promoted aggressive, sharp lines, the dresses of the 1910s were long and soft, and the corset became obsolete, though it was replaced by the girdle by many women. Likewise, both world wars would put women in occupations where pants became the obvious choice.

I think I can speak for many women when I say that whatever the reason, I am thankful for the limitless options that we now have when it comes to deciding what I put on each morning (though I do long for more opportunities to wear full skirts!).

Hi Dorothy, I have done extensive research on the topic and used to present to museum communities on this very thing! You can email me at janiceclientcare@gmail.com and I can help.

I’m writing a novel based on 1890s Scotland and I want a character to be drawn to the rational dress movement for riding a bicycle and a horse. What research materials do you recommend?

You are absolutely right, Lucy. The great part about our clothing options today is just that, the options. The fact that women can decide what feels the best to them without the static of as much social pressure gives us the ability to settle on what we love, whether it be yoga pants, skirts, high heels, or a combination of them all. Personally, I LOVE wearing really full skirts and ballet flats, similar to the fashions of the 50s. How great that I have that choice.

Thanks for reading!

All good points, Paula. The element of fashion over function or health does still have a large presence in women’s clothing today. I do think, however, that we have more choice to pick and choose what we prefer to wear, even if these choices may not be what other women would choose.

I love that I can say, I like to wear skirts more than pants!! I actually have a choice! Women of the past had to raise a big stink and never realized that choice we have in today’s society!

Of course, even now the demands of fashion outweighs good health and common sense! High heels still rule. Plastic surgery. Removal of foot bones and ribs. It’s crazy what women will do all in the name of fashion! Modern women ridicule the women of times past for their slavery to fashion, ignoring the fact that they, too, are just as much slaves!

Fortunately, we now have many more choices as to what fashion we wish to become slaves to!

I thoroughly enjoy your blogs! Thank you for sharing your joy!