Imagine a sweltering summer day in Victorian England. It is not a difficult stretch of the imagination today as we push through August, but in the 19th century, with the burden of heavy clothing and without the convenience of air conditioning, relief was more difficult to find than today. One of the joys were street vendors selling what were known as “Penny Licks.” For a penny you were given a small glass filled with the novelty known as ice cream. Then, using only your tongue, you would get several “licks” of the chilly treat. Afterwards, you would hand the glass back to the vendor and, if they were one of the more reputable ones, they would slosh it around in pail of stagnant water before giving the glass to the next customer.

Today, we no longer have to worry about Penny Licks, and due in large part to the all but forgotten “Queen of Ices,” Agnes Marshall, who revolutionized the art of frozen desserts with her innovative techniques and inventions, including the ice cream cone! During her life she was hailed as one of Victorian England’s greatest culinary figures and left an indelible mark on the world of cooking.

In Victorian England, the term “ices” referred to a large variety of frozen desserts, including ice cream, sorbets (which contained alcohol), granitas, bombes, and molded ice cream. Desserts became an art during the 19th century and many eyes were on Agnes Marshall.

BIRTH & BACKGROUND

The typical story of Agnes Marshall’s past is vague. Common lore says that she was born Agnes Bertha Smith in Essex, on August 24th, 1855. Her father was a clerk who died at an early age and Marshall’s mother remarried.

Her culinary skills were attributed to years of practical training at home and lessons abroad from leading English and French chefs. If anyone doubted her story, her husband vouched for her, saying in the Pall Mall Gazette in October 1886, “Mrs. Marshall has made a thorough study of cookery since she was a child and has practiced in Paris and Vienna by celebrated chefs.”

However, truth is often much stranger (and more interesting) than fiction. Recent discoveries suggest that Marshall was born three years earlier in 1852 and out of wedlock to a poor, working-class family in the East End of London. She was most likely raised by her grandmother and worked as a domestic servant. This would help to explain the lack of documentation for her culinary training.

To add to the mystique, in 1878 Marshall herself had an illegitimate child, named Ethel Doyle Smith (Doyle being the last name of the father). However, unlike many women in Victorian times who were looked upon as being moral failures for being an unwed mother, Marshall married Alfred Marshall the same year Ethel was born. And though Ethel was not his daughter, she was raised as such and the couple went on to have three more children. The pair successfully hid these facts from the public their entire lives — facts that in Victorian England surely would have doomed Marshall’s career hopes and respectability. (Wikipedia)

Given the societal constraints on women in the Victorian period, Marshall’s ability to invent, patent, and own inventions was quite remarkable and made possible by both her husband and a recent change in Victorian law.

Her husband, Alfred Marshall, was incredibly supportive of Agnes’ business endeavors and helped her to be seen as a respectable married woman, which in turn helped her to navigate the Victorian business landscape much more easily than most women.

She also benefited by a law which came into effect as she started her business ventures called The Married Women’s Property Act of 1882. It allowed married women to own and control property, engage in contracts without their husband’s consent, and earn and keep their own wages.

BRAND

Agnes Marshall was a pioneer at selling herself and made her name and creations into a brand long before it was common. Sometimes called the “Victorian Martha Stewart” (The History Channel), the description could not be more apt. In addition to being a remarkable chef, she designed her own kitchen equipment and sold it under her name, “Marshall’s,” helping her to become a household name.

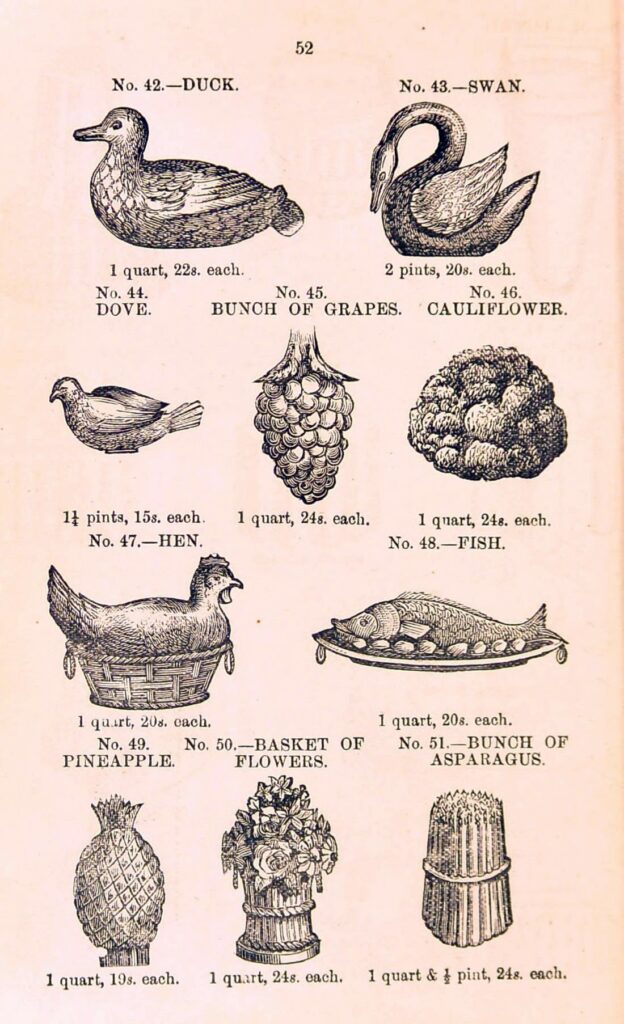

The Marshall’s also purchased a culinary school in London in1883. Naming it the “Marshall School of Cookery,” and under Marshall’s leadership and skill, her student body went from 40 students to 2000 in its first two years, with Marshall herself teaching classes as well as guest instructors eager to visit. The school focused on English and French cuisine, along with Marshall’s true passion: frozen desserts in every flavor and shape one could imagine: vanilla, chocolate, cherry, peach, lobster, foie gras, cucumber – the list is endless (and a little scary)!

The couple also opened an employment agency for those wealthy enough to hire Marshall’s graduates as their cooks. The shop inside the school sold food prepared by the students, and, of course, they sold all of Marshall’s cooking supplies, which included equipment, molds for ices, and their own spices, syrups, and food dyes. In conjunction, she also ran a weekly food magazine called The Table!

Marshall knew her audience. With her innate talent for entrepreneurial business and marketing skills, she targeted the middle and upper classes. Marshall bet these ladies would want their cooks to produce unique and ornately presented food and her school was there to guide both servants and housewives alike.

To reach this audience, Marshall conducted a nationwide lecture and demonstration on a tour she named A Pretty Luncheon. In 1888, she visited 19 cities, and drew audiences of up to 600 paying customers per lecture. After this tour concluded, she became one of the most talked-about chefs in England.

LEGACY

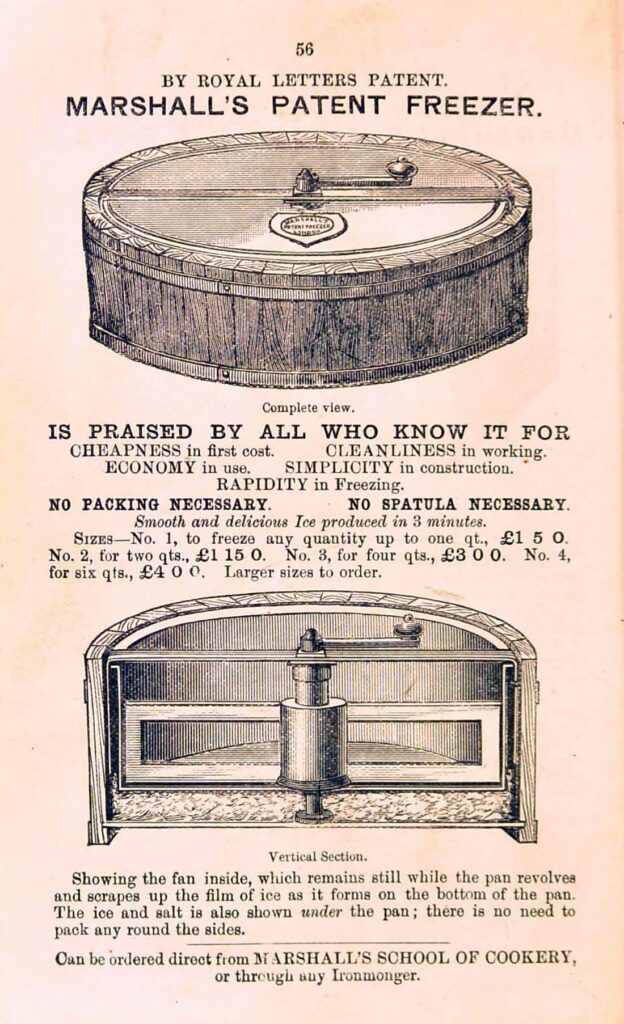

One of the most influential women of her day Agnes Marshall, wrote four cookbooks. Two of these were the most detailed and researched books ever before written on ices. She also developed a new faster and more efficient ice cream maker that produced ice cream in five, rather than twenty minutes as other machines of her time took. She is also the first person in recorded history known to put ice cream in an edible cone.

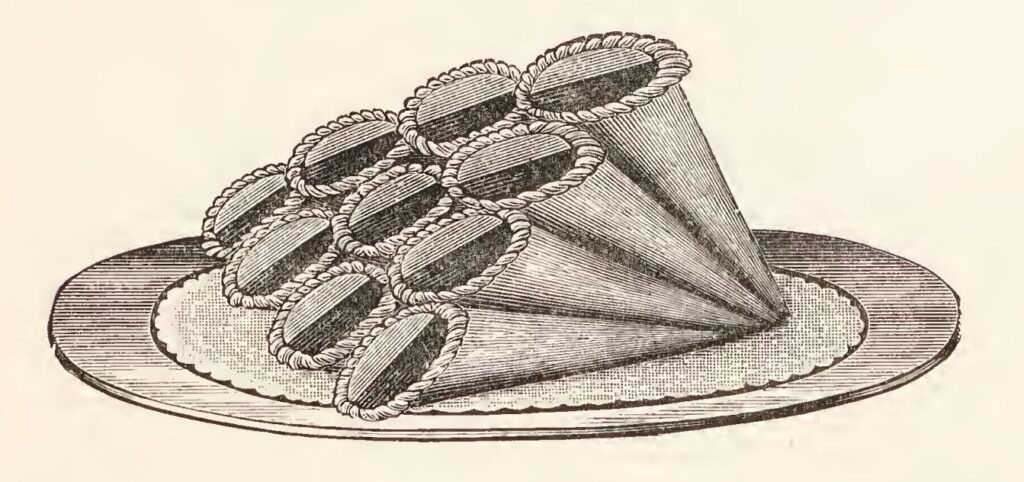

But her biggest claim to fame is that she was the first person to write about edible ice cream cones in 1888. No earlier references to such a thing has yet to be found. Marshall called them “cornets” in her book, Mrs. A.B. Marshall’s Cookery Book. She also refers to her cornets several times in her book Fancy Ices. And while history tells us that the ice cream cone was invented at the 1904 Saint Louis World Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, Marshall’s creations predate it by 16-years.

CONCLUSION

Agnes Marshall’s success and popularity as a culinary innovator helped her gain a level of respect that transcended Victorian England’s gender-based restrictions. But despite these advantages, it should be remembered that Marshall’s achievements were the exception rather than the rule. Her success was built on personal talent, but also the strategic partnership she had with her husband.

Sadly, Marshall was all but forgotten following her death. This collective amnesia was due to many factors, the main one being WWI which drastically changed people’s lives and priorities. The era of Victorian opulence was over, replaced by less labor-intensive meals, as people no longer had the resources (or desire) to prepare Marshall’s elaborate desserts. It is also a tragedy that a significant amount of her archival material was lost in a fire in the 1950s, causing a great loss to our knowledge of this incredible woman.

History is contradictory on the details of her death, but, by 1904 she was showing signs of having some form of cancer and then in 1905, she suffered a riding accident that she never fully recovered from. She passed away in 1905. But her contributions that helped to elevate ice cream from a luxury item to a popular dessert enjoyed by a wider audience lived on. It was no longer confined to the ultra-wealthy or the poor lapping it out of Penny Licks. Anyone could make it at home and Agnes Marshall ushered in an era of a love of frozen treats that still has no end in sight!

Further Reading:

Fancy Ices

The entire recipe book online, by Marshall, A.B.

– Christine Skirbunt, Author

This was a phenomenal read! Thank you for this!