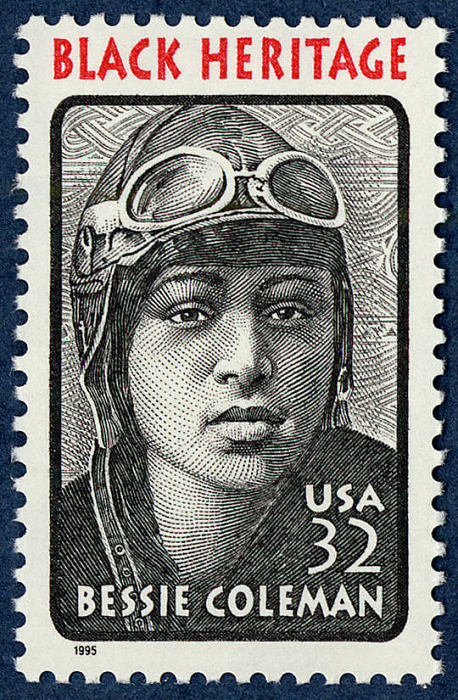

Bessie Coleman has a remarkable story and one that should be as well known as that of any other pioneering woman from the early 1900s. As we are exploring the Edwardian era this month I jumped at the chance to feature her on the blog and do my own part to make she is remembered.

Born in 1892 to hardworking sharecropping parents, Bessie Coleman came to fame in her time as a daredevil female pilot, the first Black person to ever hold an international pilot’s license, the first Native American female pilot, a speaker, and an activist. I have pulled five of my favorite parts of her story to share, along with some lesser-known photos of her career and legacy.

Flying wasn’t her first career

One of my favorite things about Bessie Coleman is how determined and how resourceful she was. When she was just a girl she told her mother that she knew she was destined for something other than the farm life and never lost sight of that vision. As soon as she was old enough, she headed to Chicago to join two of her brothers who were living there, as she knew she would have more opportunities in a large city than in a town like Atlanta, Texas, where she was raised.

She may not have known exactly what direction she would take with a career, but she did know that positioning herself around those with more resources would help her get somewhere eventually. She started out working as a manicurist, but as the great episode by The History Chicks points out, she didn’t work in a salon frequented by women. She made sure to get a job at a barbershop on one of the main streets in town, allowing her to make connections with businessmen who could afford such luxuries. This audacity was to serve her well as she worked to develop plans to launch herself into greatness as a pilot.

She learned French just to be able to apply to flight schools

Legend has it that when one of Bessie’s brothers returned from WWI he fascinated her with tales about the progressive French culture and mentioned that French women enjoyed many more freedoms than American and that they were even allowed to pilot planes. Bessie is said to have known almost immediately that she had to learn how to fly as well and had found her life purpose. But while her white female contemporaries were being the first women to be admitted to flight schools in the United States, no American school was willing to admit a Black student. Well, Bessie knew exactly where she would go to find schools to happily accept her.

The first French trip was planned. With the guidance of some wealthy connections that she had made during her time in Chicago, she supplemented the price of the trip with her own hard work. And to ensure that she would be able to apply for schools when the time came she studied French at night.

In 1919 Bessie traveled to France and would return not quite two years later as the first African American to ever hold an international pilot’s license.

She was an activist as well

Bessie didn’t forget the struggles of her family growing up nor did she forget the challenges she faced trying to become a flight student as an African American. From the very beginning, she sought to take her success and use it to make the path for others an easier one. One of her greatest ambitions became to open her own school for Black students. And while she could have easily chosen not to address the many issues regarding race at the time, she went so far as to refuse to perform in venues with segregated entrances.

According to the Bessie Coleman website, in the early 1920s, it was announced that she would appear in a film produced by a Black-owned company, a great opportunity given her love of the theater. She refused to continue with her role, however, when she received the script. Says BessieColeman.org:

“She had gladly accepted the role hoping it would help advance her career and provide her with money to establish her own flying school. But when she learned the first scene required her to wear tattered clothes, with a walking stick and a pack on her back, she refused to proceed. “Clearly, her walking off the movie set was a statement of principle,” wrote Doris Rich. “Opportunist though she was about her career, she was not an opportunist about race. She had no intention of perpetuating the derogatory image most whites had of most blacks.”

A true daredevil

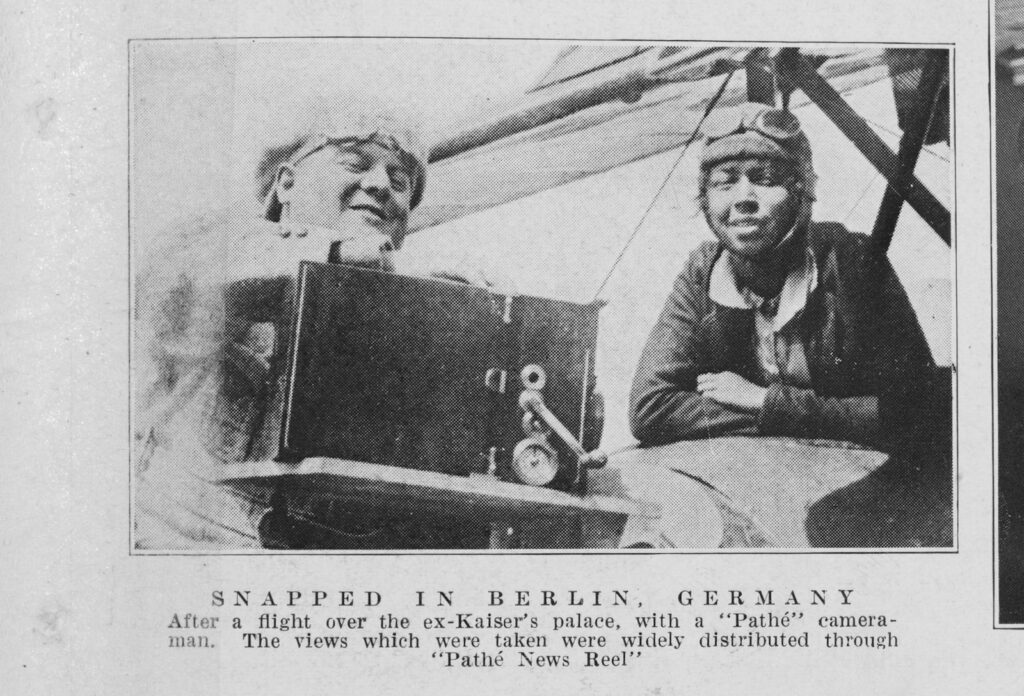

Back in the 1920s there weren’t as many ways for a pilot to make money, especially a female one. One could, however, earn money performing in air shows as the novelty of planes was quite high and interest in seeing them in action was huge. Although already famous upon her return from France, Bessie knew that in order to continue to advance as a performer she would need further training. A second European trip was made in 1922 and included training and performances in France, Germany, and Switzerland.

In Bessie’s repertoire were parachuting from a plane, figure eights; loop the loops, trick climbs (climbing on the wing of a plane in motion), and landing the airplane with the engine off. While in Germany she became known for flying the largest and most awkward plane ever flown by a woman.

Sadly, it is through this drive to become a great performer that Bessie Coleman met her extremely untimely death and may be the reason not as many readers are familiar with her story as should be. After returning from Europe her career rapidly took off. She booked shows in large cities with thousands in attendance. She also began to command large fees and book large audiences on speaking tours, which she hoped would raise money for her flight school.

Sadly, as her star was quickly rising she was thrown from a plane from 2,000 feet in 1926.

Legacy

I am glad to see that more interest is being given to Bessie’s story in the last couple of years. Surely, in her time she had made an enormous impact. Over 5,000 people attended two tributes held in her honor, with Ida B. Wells serving as the mistress of ceremonies at one. She was given a military escort to her final resting place in Chicago by members of the African American Eighth Infantry.

The African American flight school that Bessie had been so passionate about became a reality in 1930 with the establishment of the Bessie Coleman Aero Club.

BessieColeman.org lists many of the posthumous honors given to Bessie and I think they are worth noting here:

Memorial Day Fly Over in Chicago

National Aviation Hall of Fame, Dayton, OH

Chicago O’Hare Airport is on 10000 Bessie Coleman Drive

Bessie Coleman Room at FAA Headquarters

Bessie Coleman Middle School

National Great Blacks Wax Museum

Bessie Coleman Aerospace Legacy

I was also extremely touched to learn that each year a group of Black pilots flies over her grave on the anniversary of her death and drops flowers over her grave.

Let’s do our own part to make sure that Bessie Coleman’s memory lives on.

Learn more:

Bessie Coleman: An American Hero (video)

The History Chicks: Bessie Coleman

More women’s history fun:

Lillian Smith: Buffalo Bill’s other female sharpshooter

Emilie Flöge: a woman to be remembered

Hattie McDaniel’s Continued Legacy

11 Interesting Facts about Annette Kellerman, Edwardian Swimming Star

Thanks for writing these great historical vignettes! I thoroughly enjoy them and haven’t unsubscribed from the emails just because I like to read them!

Thank you so much for reading and for the kind words! It was so daunting to put the amazing life of Bessie Coleman into blog form. There is so much I had to leave out. So, it’s great to know you like it.

Janice,

Thank you for sharing this wonderful story (and links) about Bessie Coleman! While I had heard about her through other history posts, this one was the most insightful and conveyed her adventurous spirit the most. Keep up the wonderful work.

M.J.