The word “sugar plums” automatically puts me into a pure winter romance mood. And yet, like many if not most people, I don’t enjoy my holiday eating them. I have never bought or made them. And having done a lot of research on Christmas traditions from the past, although they are widely referenced, I can’t tell that they were ever as widespread as other popular holiday dishes. It’s a bit of a holiday mystery! It’s a mystery that I have unwrapped for our readers and that I know you will enjoy.

There are several elements that came together to cause sugar plums and Christmas to become such great friends, even in the abstract. It took a few hundred years and many people who are only connected through three degrees of holiday separation, and somehow we landed here.

Here’s how the lore of sugarplums came to be a phantom holiday tradition.

A singular medieval reference

I will throw my top spoiler in now. “Sugar plums” were originally not food at all, but simply medieval slang. The first reference is believed to be from 1608, in a book titled Lanthorn and Candle-light by Thomas Dekker. But rather than discussing a holiday treat, Dekker used it as another word for “bribe,” though I have not been able to find the exact quote.

The use of sugar plums to refer to sweets would not come into common use for roughly fifty years, after which there would be increasing references to it as a treat. But before it moved into something consumed, it would remain slang. For instance, if you had a “mouth full of sugar plums,” it meant you spoke sweet but deceitful words. If you “stuffed someone’s mouth with sugar plums,” it meant you were trying to bribe someone.

Sugar hits England

Similar to what we saw with our look at the history of hot chocolate, sugar came to England in the early 16th century by overseas traders. Have you ever heard the likely tall tale that Queen Elizabeth had black teeth in her later years? This story is partially based on the fact that by the late 16th-century sugar was a highly prized and highly-priced treat, used more like a spice than the main ingredient as it is today. While it was becoming more widespread by her time, it was only used by the wealthy.

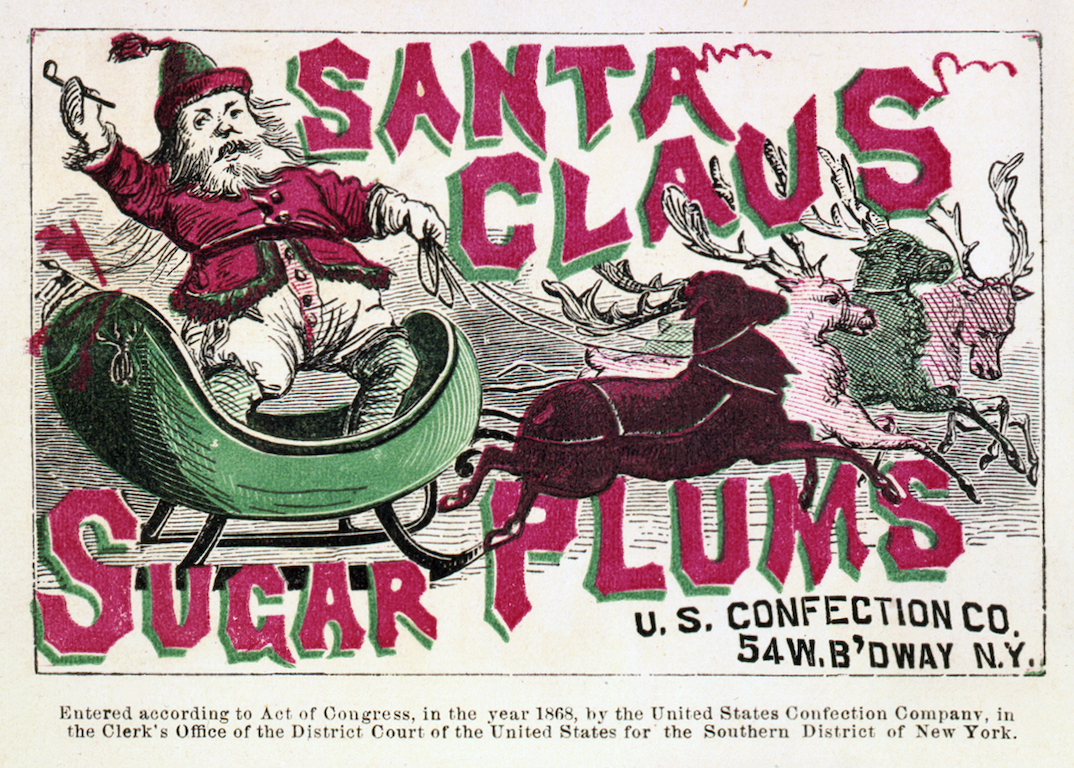

Because of being a fairly new food to the English, fairly rare, and also at the time, naturally derived, it was believed to have healing properties, also similar to chocolate. It is said that royal families would enjoy sugar-coated fruits following large, heavy meals to aid with digestion. And for decades, apothecaries carried them to treat various ailments. One of the common ways that sugar was administered would be covered on dry fruit or nuts, similar to how we think of confit fruit today. Once they moved from the apothecary counter to the candy store, confits would be referred to as plums, as the word “plum” was associated generally as a sweet treat and they were about the size of plums.

The Sugar Plum Fairy

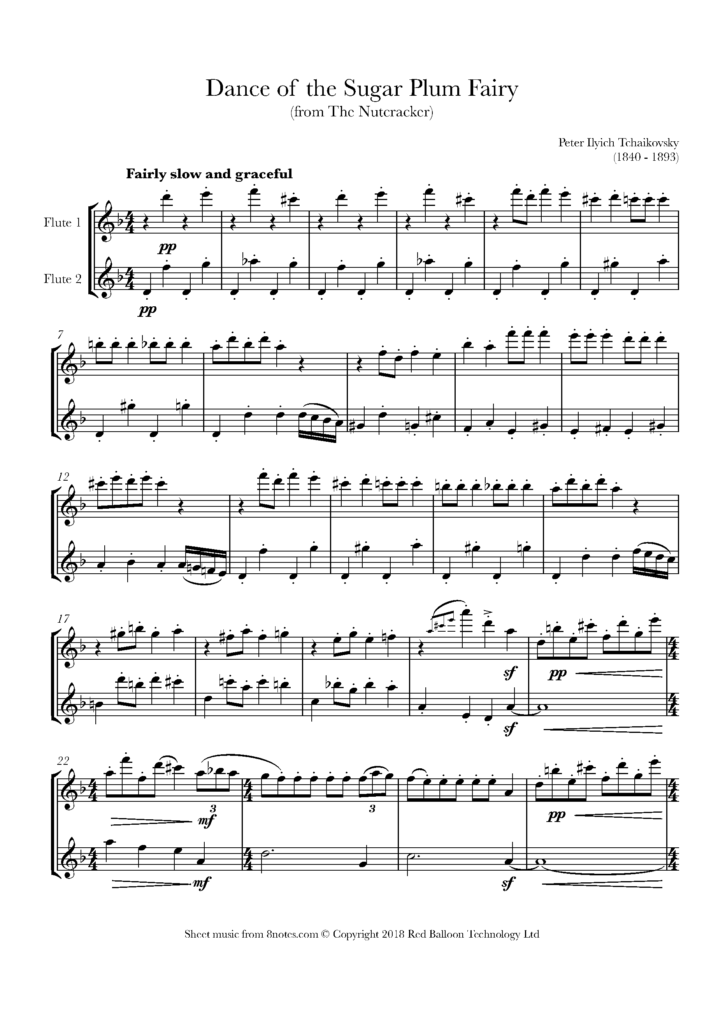

As pointed out in the delightful podcast, Season’s Eatings, while she became the most well-known character in The Nutcracker, The Sugar Plum Fairy was not a part of the original story by E.T.A Hoffman, Nutcracker and the Mouse King or in Alexander Dumas’ Tale of the Nutcracker. Instead, Tchaikovsky must have read each and believed that the Land of Sweets, referred to in each, needed a mystical fairy to reside over it.

By the time The Nutcracker hit the stage in 1892, “plum” was a very common slang word used to refer to all sweet things, food and non-food. For some time “plum” referred to a large sum of money in England, and this is why we call “plum pudding” by the name although it does not contain plums. So, it was very natural that the queen of the Land of Sweets would be named as such.

The Nutcracker is one of the reasons we still associate sugar plums with Christmas today, but is not the largest influence. Tchaikovsky’s ballet debuted to extremely lukewarm audiences. There was even a version trialed without the Sugar Plum Fairy and instead highlighting Clara and the Prince. The ballet was not performed outside of Russia until being premiered in England in 1934 and then slowly gained popularity in North America for the next several decades, especially in the United States in the 1960s.

Instead, the most significant player in the story of Christmas and sugar plums would be a little poem we will explore next.

The Night Before Christmas

A Visit From St. Nicholas was first published in 1823 and is believed to be authored by Clement Clark Moore. Today, it is one of the most well-known American poems ever written. Given that few of us celebrate a Christmas without hearing at least the opening stanzas of the poem in which sugar plums are mentioned, it is no wonder the association between the holiday and the mysterious treat has become so strong.

Now known as The Night Before Christmas, this holiday staple has a topsy turvy backstory of its own. Did you know that Clement Clark Moore didn’t originally intend on publishing it but that he merely wrote it to recite to his children as a holiday bedtime story? Or that once it was published he preferred it to be anonymous due to considering it not to be sophisticated literature? Or that the poem’s authorship is disputed?

Despite Moore’s misgivings and a bit of controversy, this poem was beloved from the beginning. Children today are as familiar with the poem as they were fifty years ago, meaning that the mysterious sugar plums will continue to remain in their Christmas Eve visions.

Sugar plums today

Though we now know that “sugar plum” doesn’t exactly refer to a traditional Christmas treat that is simply not as common today, that hasn’t stopped chefs and food websites from creating their own recipes for sugar plums. I have pulled some of my favorites to list here. If you do prepare any this year, just remember to share the truth about the history of this holiday word.

G-Free Foodie: Traditional Sugar Plum Recipe

Karen’s Kitchen: The Sugar Plum Cocktail

More holiday fun:

The 12 Days of Christmas: more than just a song

Nancy Jean Gray: Mrs. Claus extraordinaire

It’s a Wonderful Life: fun facts and setting the record straight

Very nice.I have heard every one of these, but never all together.

Actually, ‘Sugared Plums’ sound good to me.

Merry Christmas to you!

Hello! I do so enjoy reading your column! It is always interesting and informative.

I actually grew up eating sugarplums during the holidays. My family is from New Orleans, and sugarplums used to be very popular. Fresh fruit was dipped in liquid egg whites (or meringue powder mixed with water), and then rolled in casting sugar. After the fruit is dried, it is artfully arranged on a dish or platter. You should use pasterized eggs or meringue powder to avoid salmonella. Sugarplums are eaten with tea, as a snack, or as a dessert. This holiday favourite is seen less and less as time goes by. Post Katrina New Orleans has had many traditions that disappeared completely after the massive hurricane. It is to be lamented that so many traditions have gone by the wayside.