We hope that everyone had a great Thanksgiving! The holiday shopping season is here! We love offering you special discounts as part of the beginning of the holiday shopping season and of course, Black Friday.

Some believe that the term was created to refer to the fact that the holiday season supports retail establishments to get into “the black” for the year, with the day after Thanksgiving being the first day. The theory is largely debunked, however, becoming now dubious at best. Here are five theories and fun facts about Black Friday history that you will enjoy pondering as you enjoy your shopping this weekend.

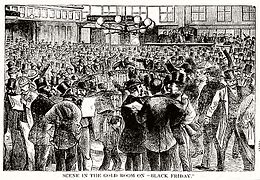

The first Black Friday?

Most sources point to the Panic of 1869 as the first reference to a Friday as “black.” Do note that it was used in a highly negative context, not as a celebratory one that called in the survival of shops around the country.

The Panic of 1869 occurred when two social-climbing scoundrels, Jay Gould and James Fisk came up with the idea to use their connections with President Grant’s administration to dominate the gold industry. Interestingly enough, one of them was married to Ulysses Grant’s younger sister, Virginia Grant, who was in on the scheme.

President Grant would have none of it, especially having his name connected with the plot. He ordered the treasury to release an inordinate amount of gold, causing those involved and others to lose their fortunes. It would be referred to as Black Friday for several decades to come.

Are you ready to shop? Start with our store-wide 25% off sale.

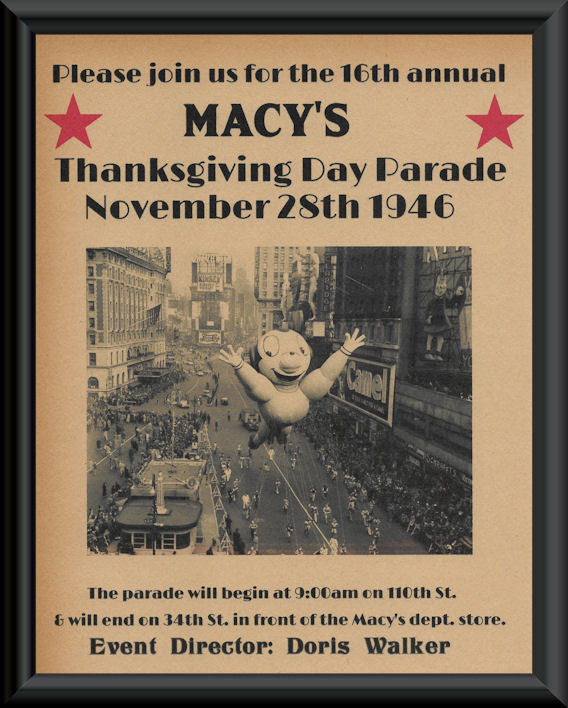

Did parades create the chaos?

The name aside, where did the Christmas shopping chaos come from? I, along with other history lovers, point to good old marketing, most notably, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

What a brilliant concept it was and is.

I am a bit of an expert on the history of the parade. One cannot deny the link between an enormously large, televised, consumer-worshiping event happening on Thanksgiving and the day after being so shop-happy. I may blame Macy’s, but I thank them as well, as I sure do love to watch the parade.

Roosevelt to blame?

The Franklin Roosevelt connection to the holiday shopping season is an interesting one, and one I wasn’t aware of until this week. Wanting to pump up the economy and also listening to retail lobbyists, he got the idea that a longer shopping season would be good for the country.

Since its official inception, Thanksgiving had been held on the last Thursday of November. The President had an idea. In 1939 he took it upon himself to really shake things up, moving it to the third Thursday in the month by presidential decree.

Retail conglomerates may have jumped for joy, but it wasn’t an overall popular move. Says Time Magazine:

Many people were not happy about the change, as TIME reported the week after it was announced:

Only since 1863 has Thanksgiving had a consistent year-to-year day, but football coaches were furious: 30% of them had games scheduled Nov. 30 which would now play to ordinary weekday crowds. Calendar-makers took the blow quietly except for Elliott-Greer Stationery Co. of Amarillo, Tex., which happily discovered it had designated Nov. 23 as Thanksgiving Day by mistake. Alf Landon sounded off in Colorado as follows: “. . . Another illustration of the confusion which his impulsiveness has caused so frequently during his administration. If the change has any merit at all, more time should have been taken in working it out . . . instead of springing it upon an unprepared country with the omnipotence of a Hitler.”Yes, Roosevelt’s Republican rival did just compare FDR to Hitler because of this.

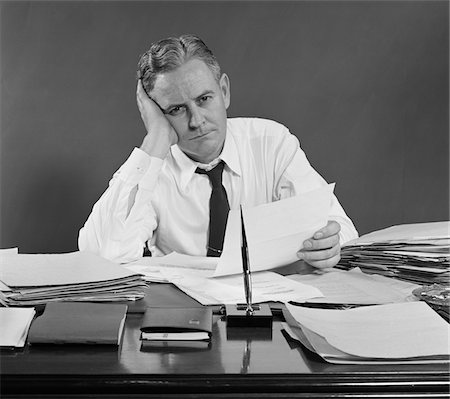

Do we really have to work today?

And now for my favorite theory about the origin of Black Friday. In 1951 an editor for the Factory Management and Maintenance journal wrote an editorial bemoaning the hardship so many factories faced each year when the day after Thanksgiving rolled around. The problem? Many a worker chose to call in sick.

I was delighted to find a copy of said editorial. It reads:

“Friday-after-Thanksgiving-itis” is a disease second only to the bubonic plague in its effects. At least that’s the feeling of those who have to get production out, when the “Black Friday” comes along. The shop may be half empty, but every absentee was sick — and can prove it…

While I don’t know that I approve of the editor’s bad attitude, I do approve of one of the solutions he put forth: that the day after Thanksgiving should be given as another paid holiday. The idea caught on, and many of us are thankful for today.

Enter Philadephia traffic

So now to the most widely referenced idea about where the term Black Friday as we know it came from.

The idea still comes back to my theory of Macey’s and others creating a shopping extravaganza starting the day after Thanksgiving. But mid-century Philadelphia apparently caught it really hard.

There’s additional evidence to suggest that this unflattering term originated among police in Philadelphia. The late Joseph P. Barrett, a longtime police reporter and feature writer for the Philadelphia Bulletin, reminisced about his part in the use of Black Friday in a 1994 Philadelphia Inquirer article headlined, “This Friday Was Black With Traffic”:

In 1959, the old Evening Bulletin assigned me to police administration, working out of City Hall. Nathan Kleger was the police reporter who covered Center City for the Bulletin.

In the early 1960s, Kleger and I put together a front-page story for Thanksgiving and we appropriated the police term “Black Friday” to describe the terrible traffic conditions.

Once again I was able to find the direct source for this reference, so that part is at least legit.

More holiday season fun:

A very Vintage Thanksgiving to you!

A very, merry 1950s Thanksgiving

Leave A Comment