August 2020 is here and that means it is time to celebrate the hundred-year anniversary of the passing of the 19th Amendment on August 18th, 1920. I was planning on celebrating with a lot of in-person events, but instead, I’m celebrating from behind my computer screen in many ways. One way is by writing blog posts about the suffrage movement in an attempt to make sure that the stories of the women who fought for the vote don’t get forgotten.

To start things off this month, I thought I’d explore the use of the terms “suffragist” and “suffragette.”

Here at Recollections, we have received feedback from time to time on the use of the term “suffragette” popping up on the website. Personally, I have a degree in women’s studies, and hearing the terms used inappropriately is a minor pet peeve of mine. That being said, there is a lot more to it than one word being “right” and one word being “wrong.” In fact, there is even more to it than I knew before doing some research for this post.

So, is the term “suffragist” or “suffragette”? To understand both the question and the answer we must take a look at the British and American woman suffrage movements and the parallels and differences between the two.

The British Woman Suffrage Movement

One could argue that the woman suffrage movements in the United Kingdom and the United States were cousins. In timeline, dynamics, and tactics, the two correlated and overlapped frequently. Not only that, but the respective members knew each other, corresponded, and supported one another. Famously, before starting the National Women’s Party, Alice Paul spent time in England working with Emmeline Pankhurst and learning about militant protesting. The influence that each had on the other is undeniable.

The movement for the British female vote started to pick up major steam in the 1860s with the election of John Stuart Mill to parliament. Mill was a well-known advocate for equality of the sexes, and activist organizations started to spring up around the country, emboldened. Of note was the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, founded by Lydia Becker. The primary approach to the vote was similar to the American movement, to secure a constitutional amendment. Activists worked tirelessly to work in the existing framework as decades rolled on.

A split in the movement

As the 20th century arrived, a growing contingency of women had become frustrated with the lack of achievement the movement had gained. Many felt that a shift in approach was necessary if they were going to gain the attention needed to succeed.

Enter Emmeline Pankhurst.

In 1903 Emmeline and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) with noticeably different tactics to demanding equality. While the movement up to that point had stayed “refined” and focused on actions such as dinner parties and meetings with men in leadership positions, the Pankhurst’s took an “in your face” approach. While they engaged in traditional tactics such as parades and marches, they also employed violent and extreme tactics such as chaining themselves to gates, planting explosives, and various types of vandalism.

The press took note of this break-off movement. Famously, in 1906, journalist Charles Hands referred to the group as “suffragettes” in an attempt to belittle both the younger age of the activists and insult their strategies (I have searched high and low for the original reference and have not located it yet).

Savvy as can be, the new militant arm of the movement embraced the term, taking the wind out of the sails of critics and setting themselves apart in the fight. In the beginning, many used the term in print as “suffraGETes,” implying that they would be the ones to GET the vote.

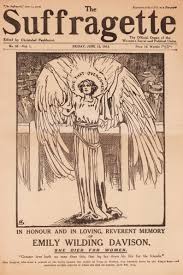

The WSPU went so far as to name their newspaper The Suffragette.

From then on out, the terms “suffragist” and “suffragette” were used to refer to the different groups’ fight for the female vote, both in and outside of the movement.

The American Suffrage Movement

While there are many clear overlaps between the British and American woman suffrage movement, the appropriation of the term “suffragette” is not one of them.

The term did make it across the pond but was picked up by critics and journalists as a derogatory word for any woman involved in the campaign for the vote. Rather than reclaim it as the militant British activists had done, even the more “in your face” suffragists such as Alice Paul deemed the word an insult and never used it.

Many readers will be familiar with the split the American woman suffrage movement between Carrie Chapman Catt’s National American Woman Suffrage Association and Alice Paul’s National Women’s Party. The reason for the split was an irreconcilable difference in opinion on approach, with Alice Paul wanting to take what she had learned from the Pankhurst’s to the campaign. So why didn’t NWP also adopt the term “suffragette”?

While this is a topic that could lead to significant research, my theory is that while NWP saw the validity of some of the tactics employed by the militant activists in England, they also saw that it would be prudent to keep some distance. Picketing the White House during WWI was seen as extreme enough, aligning themselves with the suffragettes who were throwing rocks thorough windows or planting explosives wasn’t necessary. I believe that the decision not to self-identify as suffragettes was just as deliberate as the decision by English activists to use it.

In any case, the word was used for the duration of the fight for the vote by critics to demean and mock the growing number of individuals involved in the cause.

Why is the term so misused in America?

Before you go angrily correcting anyone who uses the term “suffragette” this August, consider the following.

The very fact that the term “suffragette” was ever offensive to women fighting for the vote may come as a surprise to some readers. If you are anything like me, you may listen to various history podcasts, for instance, and hear the term used without correction (it’s sort of like nails on a chalkboard to me). While it is true that the use of the term to refer to women in the US movement is incorrect, there is a bit more to it than that.

Use of the term in other countries

In preparation for writing this post, I turned to the New York Times archives to run a search for the term and was quite surprised by what I found. It is true that few if any, references to American “suffragettes” can be found during the movement itself. In the 1930 and 1950s, however, I found many references to stories involving “suffragettes” in other countries still working to get the vote, France and Egypt in particular. As neither country is English speaking, I have found it hard with limited time to fully ascertain whether “suffragist” or “suffragette” is the equivalent of the terms activists used to self-identify, but I was able to find the French translation of the word as such in one instance.

referring to her as a “suffragette.”

Unchecked misuse in the 1960s and 1970s

So there’s that, the term seems to have caught on in other countries and was used in American newspapers in a non-derogatory way in the 1930s and a bit in the 1950s. The instance of its use then goes down until the 1960s, when I began to see it employed by New York Times journalists to refer to American members of the movement who were making appearances, involved in other causes, or passing. Seemingly, it went uncorrected and the term stayed in use in highly respected outlets through the 1970s at least.

The second wave of feminism brought with it a level of scholarship that caused many feminists to effectively shift the most popular word used to describe suffragists as “suffragists.” It is an effort many are keeping up today. In a July 2020 New York Times article about a roundtable discussing the American movement, noted authors and women’s studies scholars Susan Ware and Elaine Weiss both started the discussion by addressing the topic. Both stated that the term was “never” used by women in the American movement and implored the New York Times to never use “suffragette” unless including quotation marks around it. Ware, the author of Why They Marched told the group that she had gone so far as to write former presidential nominee Hilary Clinton to correct her: “I tried to write to Hillary Clinton a few years back to tell her that she was using it incorrectly. I wrote this nice, long letter and I said, “I’m a Wellesley graduate,” and so on. I never heard anything back. That was really infuriating to me, because she has brought a lot of attention to the suffrage movement. And yet she calls them “suffragettes.”

Suffragist or suffragette? Now you know the rest of the story…

What did you know about the terms “suffragist” and “suffragette” before reading this article? Does anything surprise you?

Thank you for reading and for pointing that out! Typos can happen when you write weekly posts 🙂

I’m glad you liked it!

As someone who uses the suffrage fight in America as an example of civil disobedience for her American Lit students, I thoroughly enjoyed this piece. I did know that suffragette was used only in Britain.

At one point in the article, though, I think you used “adapt” when you meant “adopt”: ‘So why didn’t NWP also adapt the term “suffragette”?’