The Industrial Revolution brought many and lasting changes to the labor force. We moved from a mostly agricultural society to one dominated by mechanization. Men, women, and children as young as five worked long hours in often dangerous conditions. It wasn’t unusual for people to work 12 hours a day, seven days a week for very little pay. Children were paid a fraction of what an adult earned.

The beginning of the labor movement

Labor unions came into being at the end of the 18th century. They grew in size and prominence during the 19th century, becoming the voice of the ‘workingman.’ Strikes and rallies to expose and protest poor working conditions became more commonplace.

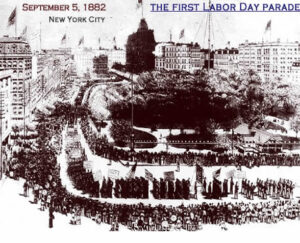

The first Labor Day parade in the United States took place on September 5, 1882, in New York City when “10,000 workers took unpaid time off to march from City Hall to Union Square.” They were protesting low wages, excessive work hours, and unsafe working conditions. Participants included “cigarmakers, dressmakers, printers, shoemakers, bricklayers and other tradespeople.” Afterward, everyone enjoyed a picnic in the park.

A second Labor Day parade, organized by the Central Labor Union was held on September 5, 1883. By 1884, it was decided that the annual celebration of the workingman be held on the first Monday in September. In 1885, the idea spread to many cities in the USA.

National attention for the movement

The first state to pass a law recognizing the holiday was Oregon on February 22, 1887. By the end of the year, Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York also adopted the holiday. By the end of the decade, Connecticut, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania also recognized the holiday.

It took a national strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company to bring Labor Day to national prominence. When the company lowered wages, it didn’t lower the rent it charged employees living in company housing. When workers complained, they were fired. A strike followed and other workers for the American Railway Union joined the strike.

Freight and passenger service ground to a halt in and around Chicago when workers refused to handle Pullman cars. Tensions grew on both sides of the labor issue. To recognize the workers’ struggles and to retain the support of the working-class voters, President Grover Cleveland signed a bill on June 28, 1894, that made Labor Day a national holiday.

Celebrating our workers today

Today, we mostly celebrate the holiday with barbecues, picnics, and other family activities. It marks the unofficial end of summer when many children return to classrooms. But, we also recognize those who are the workforce that makes our nation strong. We offer gratitude to everyone who “works hard for the money.” We thank our dedicated cutters, seamstresses, finishers, shippers, and office workers who make Recollections more than a company.

Do you love turn-of-the-century history? Create a look of your own!

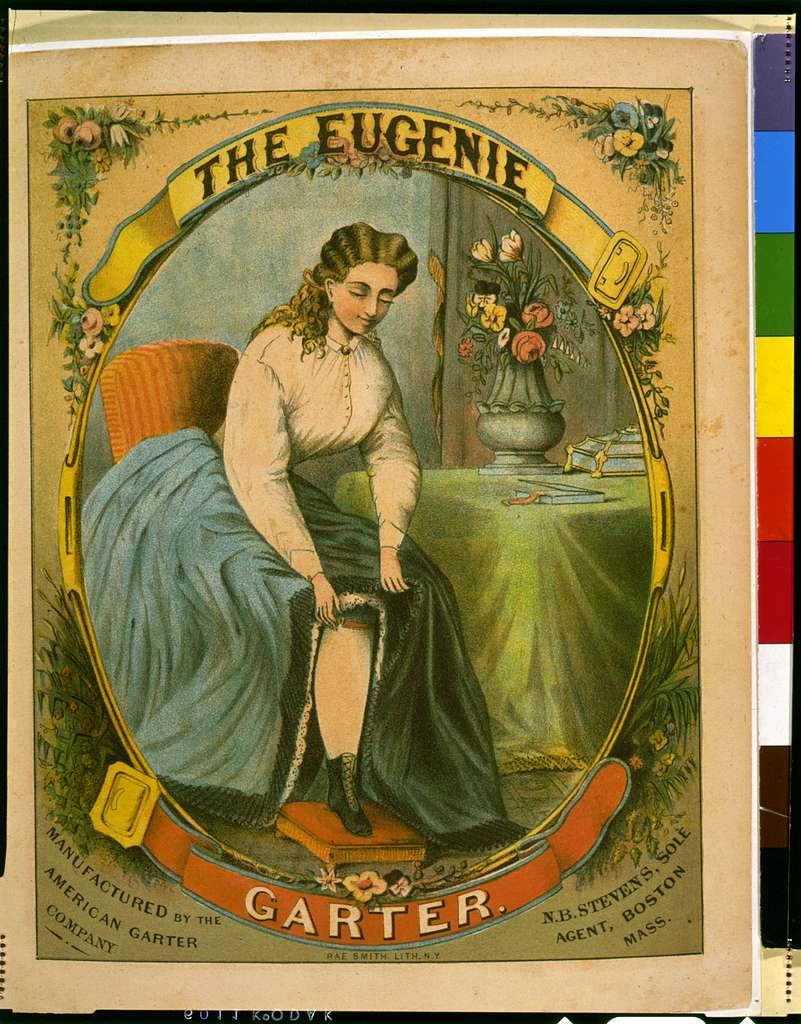

We invite you to browse the history-inspired fashions that are designed and made by the women of Recollections. Here is an example of some of the clothes women might have worn to work around the turn of the 20th century. Women’s office dress code often required a white blouse and a black or dark skirt, such as our Pleated Edwardian Blouse. Our Agnes Charcoal Pinstripe Edwardian Dress and pretty chemisette transition to a work environment quite nicely. Paired with a white blouse, our Edwardian Vest and Skirt set is ready to go to work.

- Pleated Edwardian Blouse with dark skirt – typical officewear

- Agnes Charcoal Pinstripe Edwardian Dress

- Edwardian Vest and Skirt

More American history:

5 facts about Betsy Ross and the origins of the American flag

Suffragist or suffragette?

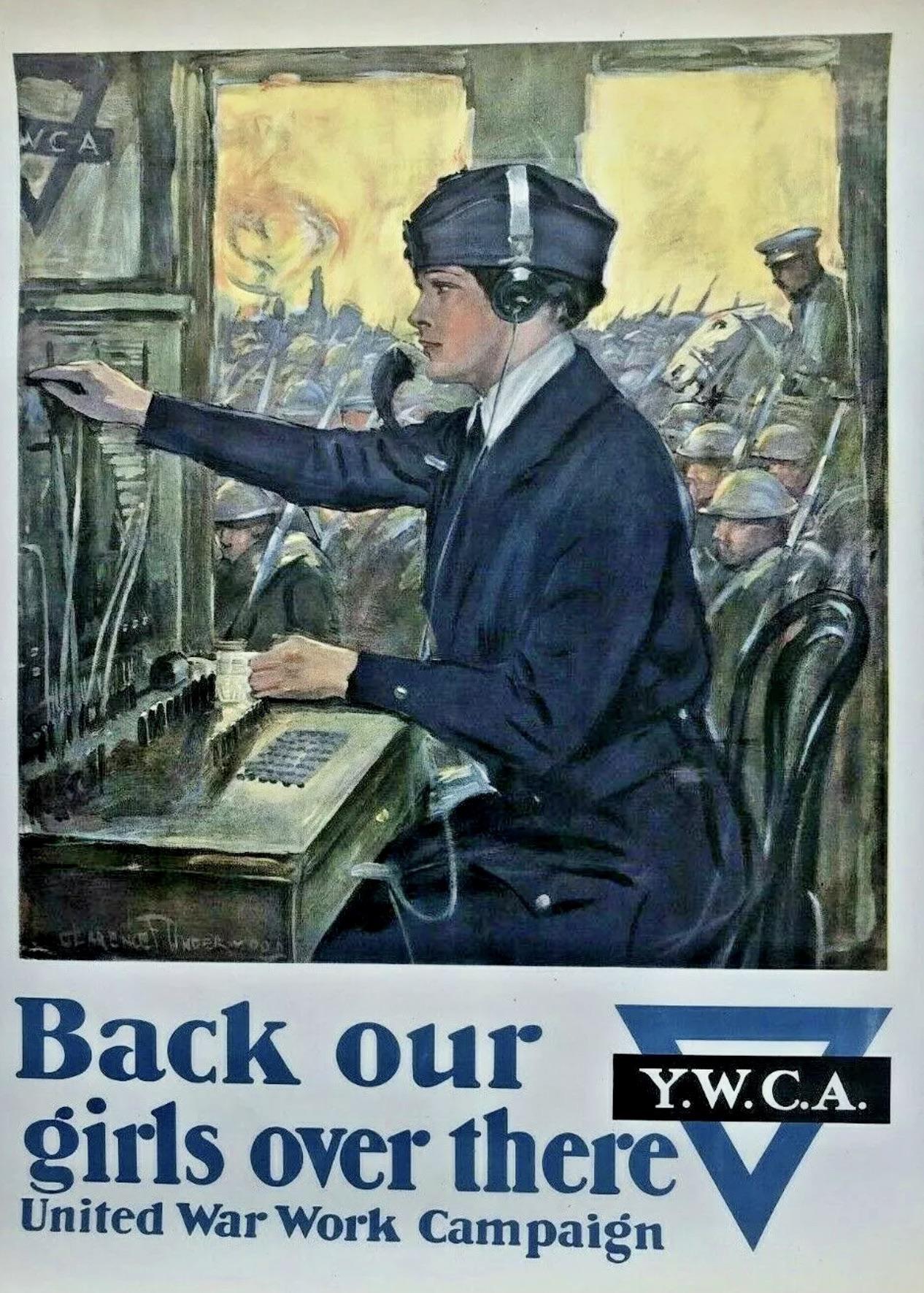

Veterans Day: Recognizing American Women in WWI

Leave A Comment