Queen Victoria goes into mourning

In December of 1861, Queen Victoria’s beloved husband Albert died. Her response to his death would forever change Victorian mourning clothing and customs. It had been the custom for a widow to wear black for a period of one year; other relatives were in mourning for lesser periods, depending on their relationship to the deceased. However Victoria donned black and went into seclusion for almost five years after Albert’s death. At her instruction, all of her staff also went about in mourning. For a year after Albert’s death, no servant of the household could appear in public, except in mourning. This might have continued indefinitely, except that the morale of the ladies at court fell so low that the Queen finally relented, and permitted “semi-mourning” colors of white, mauve, and gray. Royal servants were obliged to wear a black crepe band on their left arm until 1869.

Changing Victorian mourning customs

Full mourning

Because this much-loved Queen had such a huge impact on style, the depth of her mourning affected the rest of the Victorian world – even in America – and a large body of customs developed surrounding mourning. These customs had the greatest effect upon a widow, who must observe two years of mourning for a deceased husband. The first year and one day were called “deep mourning” or “full mourning.”

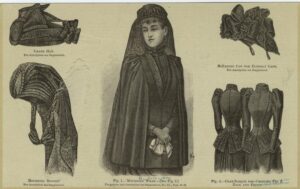

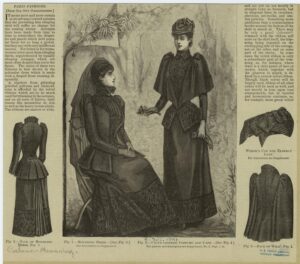

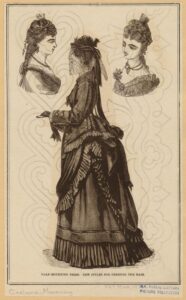

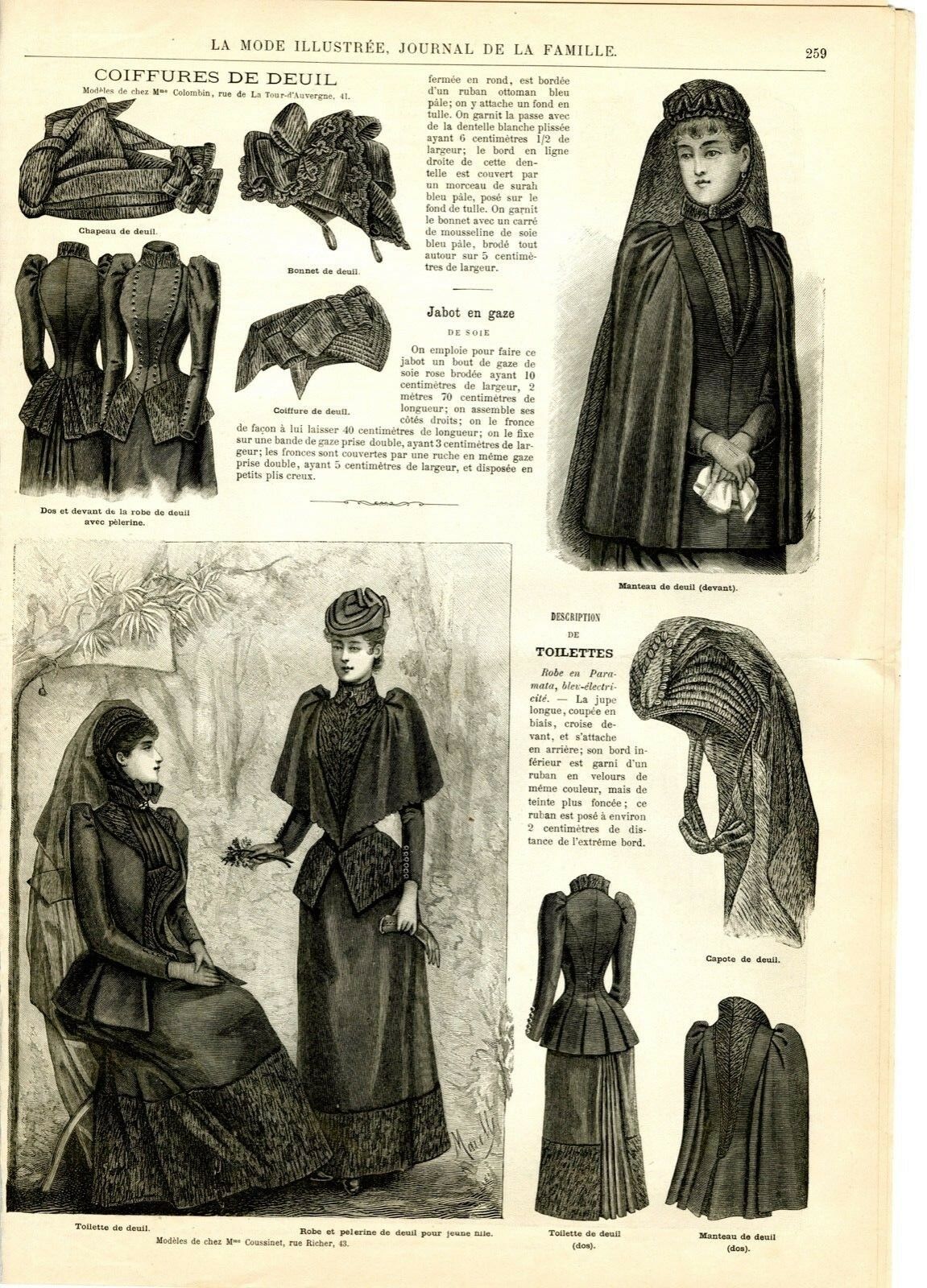

During full mourning, the clothing the widow wore was strictly dictated. She might wear no color other than black, and the preferred fabric was black crepe. Crepe had no sheen, and had a slightly wrinkled surface – much like crepe paper that we see today. She was to wear a widow’s cap, which featured long black streamers (veil), or ribbons. She was not to wear any jewelry except jet. Her hose and gloves were also black. If it was winter time, fur was permitted, but only dark fur was allowed. She was completely isolated from society for the first three months, except for church attendance. She might not even be permitted to attend her late husband’s funeral, such was her isolation. When she did appear in public, she wore a “weeping veil” which fell to mid-calf.

Half mourning

During the second year of mourning, called “second mourning” or “half mourning” widows could dispense with the widow’s cap, and silk was permitted for her dresses – but was still to be “trimmed deeply” with crepe for at least another 9 months. Dark fur was still permitted. During the second year, she was permitted to start wearing other colors, although it was recommended that the transition be made gradually, and no bright colors were to be worn right away.

In addition to their outer wear, widows were encouraged to have even petticoats in black, or at least hemmed with a deep black hem. Otherwise if a widow were ascending a stairway or stepping over a curb, there might be an unseemly flash of white at the hem of her dress. Even her handkerchief was to be at least bordered in black, as was her personal stationery.

Men and children in mourning

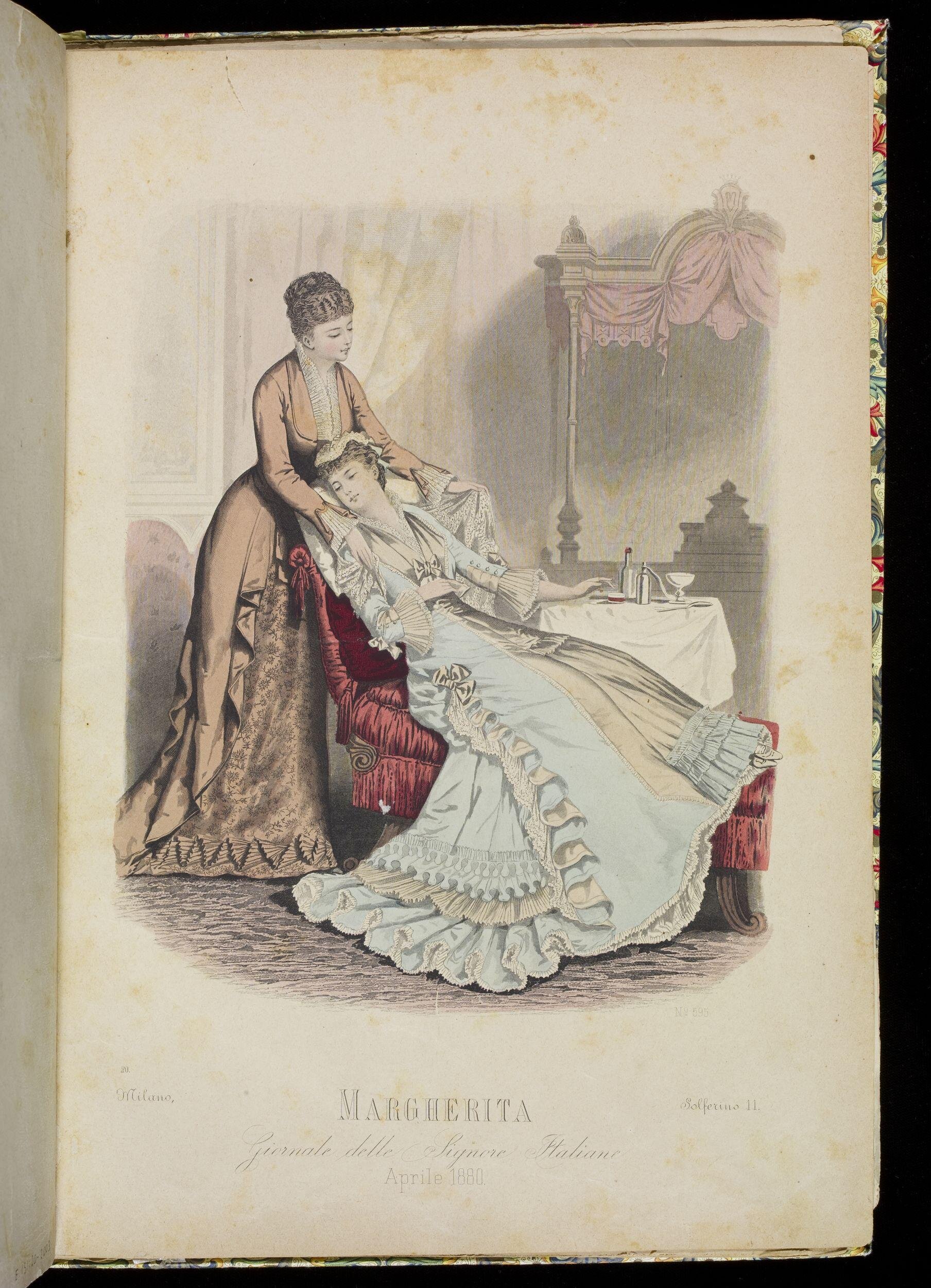

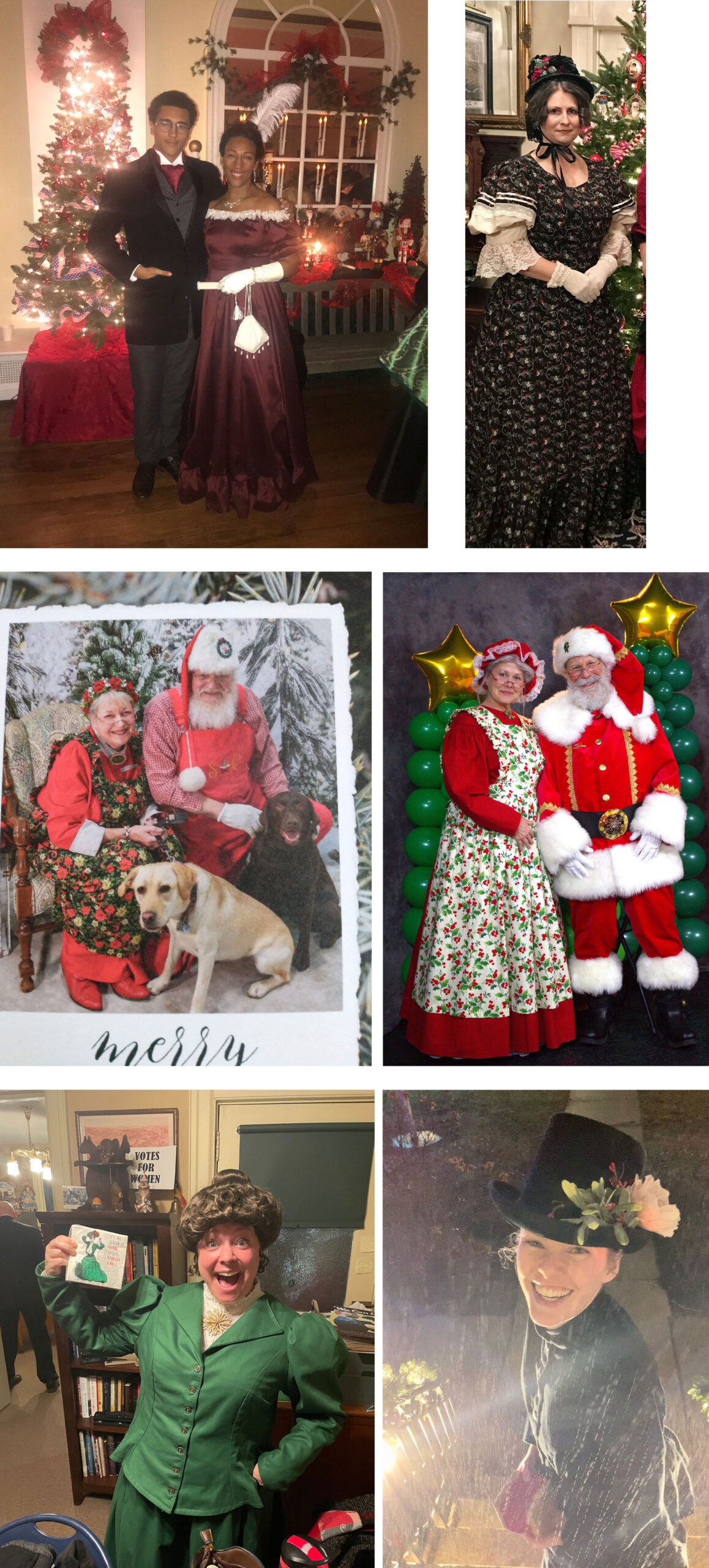

Girl’s mourning outfit. Image source: V&A Museum.

Men and children were also required to dress for mourning. Men wore a black suit and a black armband. If a man lost his wife, he might dispense with the armband, and was encouraged to find a new wife as soon as possible to care for his children. Children’s mourning attire usually consisted of white trimmed with black in the summer months, or gray trimmed in black if it was winter time.

The creation of the Victorian mourning industry

It should be noted that none but well-to-do ladies could afford to buy entire new wardrobes for mourning, although mourning clothes were among the first “ready-made” clothing for women to be offered in stores. In order to appear stylish, most simply dyed everything they owned black. The dyes were so toxic that the dyeing process itself could cause illness, and wearing these hand-dyed fabrics caused any number of skin and eye ailments – up to and including blindness. So pervasive were the mourning customs that entire fabric mills were devoted to producing nothing but crepe.

Hairwork jewelry grew out of the desire to keep a remembrance of a loved one who had died, as it was common practice to clip a lock of a loved one’s hair as a keepsake. In 1850 Godey’s Lady’s Book introduced the craft of hairwork to American women, and the creation of hairwork brooches, wreaths, bracelets, and other items became a popular pastime; though not always used as a memorial.

Want to learn all about the history of hair jewelry and see some amazing pieces? Check out our blog post: Victorian hair jewelry: yay or nay?

More about Victorian culture:

The Victorian Croquet Craze: crazier than you think

Victorian letter writing rules

Before selfies and text messages there were friendship books

Leave A Comment