I love to study trinkets from time. Some of my recent ideas have come from research I did last year for a post on women’s tie-on pockets. Among the many items that were commonly carried in the deep, under-the-skirt pockets of the 19th century were thimbles. It struck me that women would be ready to sew at a moment’s notice, but also led me to consider other reasons a woman may have carried a thimble in those times. Surviving examples are often of an elaborate nature so I wondered if they would have been kept for novelty reasons, similar to the lockets or miniature portraits also kept in pockets.

While they began as highly functional items, thimbles would eventually become status symbols, representing the thoughtfulness of a lover or the places one has traveled.

Read all about what women kept in their tie-on pockets on our blog post: Private purses: women’s tie-on pockets

But it would all begin with avoiding pinpricks in ancient times…

Early thimbles

The earliest examples of a barrier to be used when sewing were actually designed to protect the palm of the hand. This is likely because materials such as animal hides were so thick that the entire hand was required to push the needle through. There are similar examples that may have been used to place over a finger rather than attached on top. China is often credited as being one of the earliest regions to employ such technology, and many believe that explorers brought the concept back to England in the 14th century.

The thimble below dates to 1295–1070 B.C., Ancient Egypt.

In the modern European history of the thimble, Nuremberg is often featured as the first main player.

The one below is from Nuremberg, circa 1577. This is because we see the manufacturing of thimbles in areas with high brass and bronze work taking place. Nuremberg was known for its innovations in brass and thimbles from the time and region are characterized by having two pieces of brass fused together as seen below.

Image source: V&A Museum

The next thimble influencer would be the Netherlands, also because of its brass manufacturing.

Image source: V&A Museum

Taking thimbles to England

It would, in fact, be a Dutchman who would bring thimble-making to England in a big way. Discovering that there was little thimble production in the British Empire, in the 1690s John Loftnick sought to establish and corner the market. He is still credited today for the mass production of thimbles around the world. Says the Marlow The Marlow Society seeks to preserve the history and heritage of Bisham, Great Marlow, Little Marlow, Marlow Town, and Medmenham. Of Loftnick’s thimble empire they write:

“Seizing on a potentially lucrative business opportunity, Lofting moved to London and set up his own business making thimbles in Islington, where there is a road named after him today. He was clearly an astute businessman, for he realized that making thimbles by hand was inefficient and expensive, so he set about designing a machine to automate the process, and by 1695 he patented the design. His machine could cast, turn and indent the thimbles very much more quickly than could be done by hand. At first the machines at his Islington factory were horse powered, but in 1697 he relocated his machinery to Marlow, where he took a lease on Marlow Mills with the aim of using water power instead of horse power. At first his business got off to a slow start as he found a shortage of appropriately skilled workers in Marlow. However he must have surmounted this problem because, before long, it is reported that the change from horse to water power allowed Lofting to double the output he had achieved in Islington, and before long he was able to produce up to two millions thimbles a year.

It has proved difficult to source any attributed to a Loftnick mill, though I have found a collection of the same style from the same period.

Forget me not

Thimbles were popular gifts for young women, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries as mass production sped up and they became more intricate and beautifully designed. Apparently, gift giving during courtship was tricky business, with societal rules dictating that a man not select something too personal or elaborate such as a shawl or jewelry (I am glad this rule has changed!). A thimble was seen as just thoughtful and common enough. They were also given between friends.

1830, V&A Museum

1760-1780.

Image source: MetMuseum

As the technology used became more advanced, thimbles quickly began to be used to mark big events and holidays. Take, for instance, the example below made to commemorate Queen Victoria’s jubilee.

Thimbles created and collected for the sole purpose of being keepsakes is likely led to the introduction of porcelain, as the material is less ideal for working with needles.

Advertising thimbles

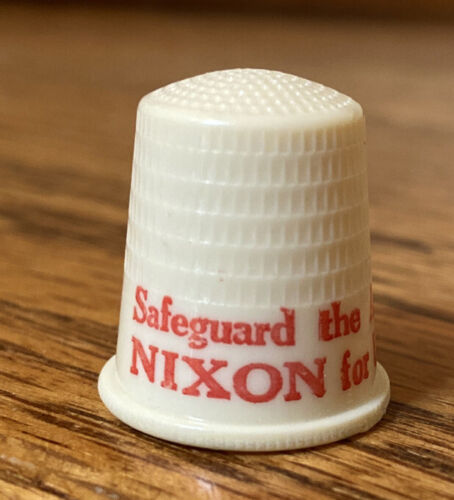

When the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, political candidates sought to win over the new female bloc with thimbles supporting their campaigns. Warren G. Harding was perhaps the first, followed for decades by others. Remarkably (to me at least) I found many such campaign swag on sell through eBay and others.

Image source: eBay

Image source: eBay

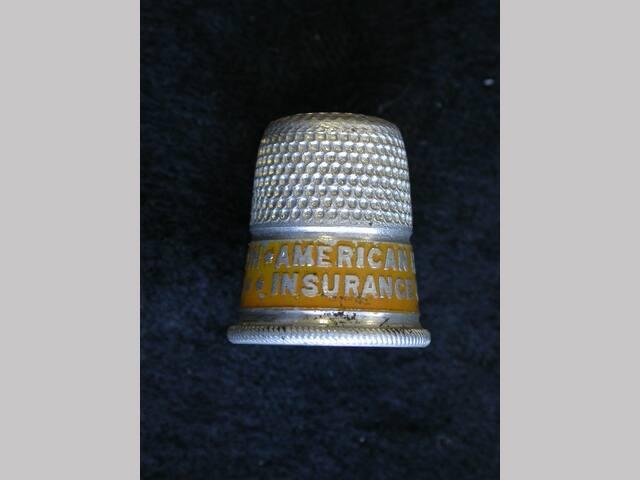

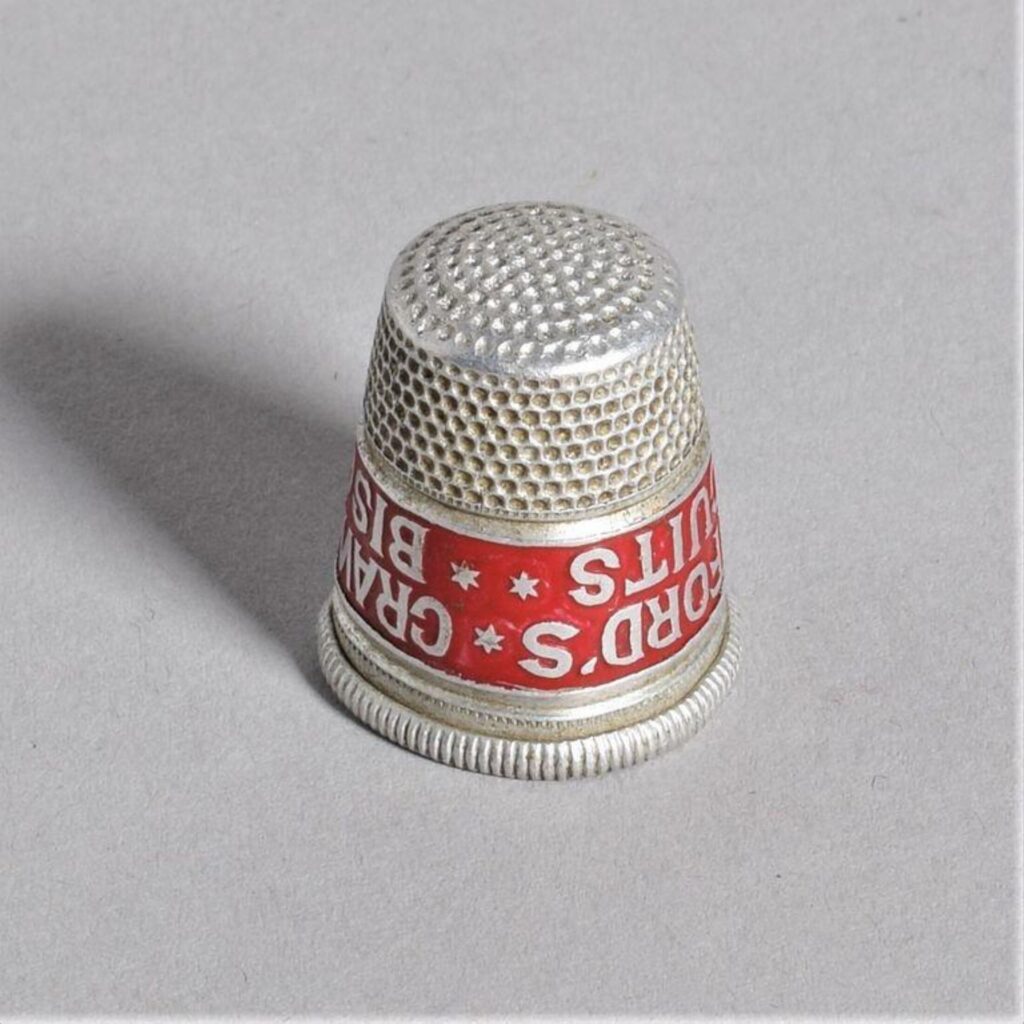

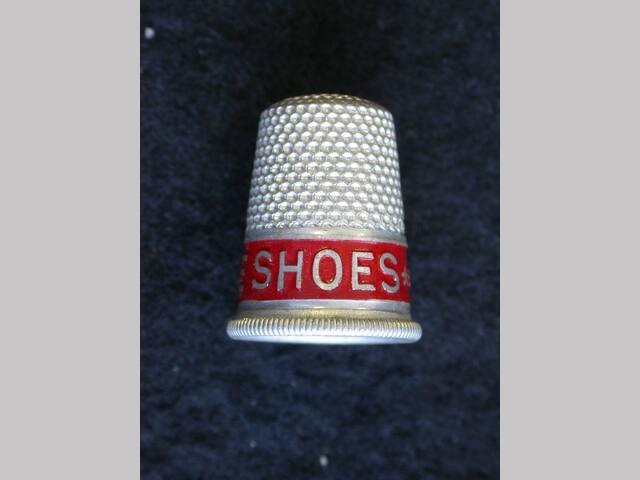

Perhaps because of their eventual easy and inexpensive production, metal thimbles were also used for advertising purposes. I think these are my favorite types.

Image source: New York Historical Society

Image source: V&A Museum

Image source: V&A Museum

More trinkets from time:

That’s write! Inkwells through time

19th century spicy trinkets: Nutmeg graters

Leave A Comment