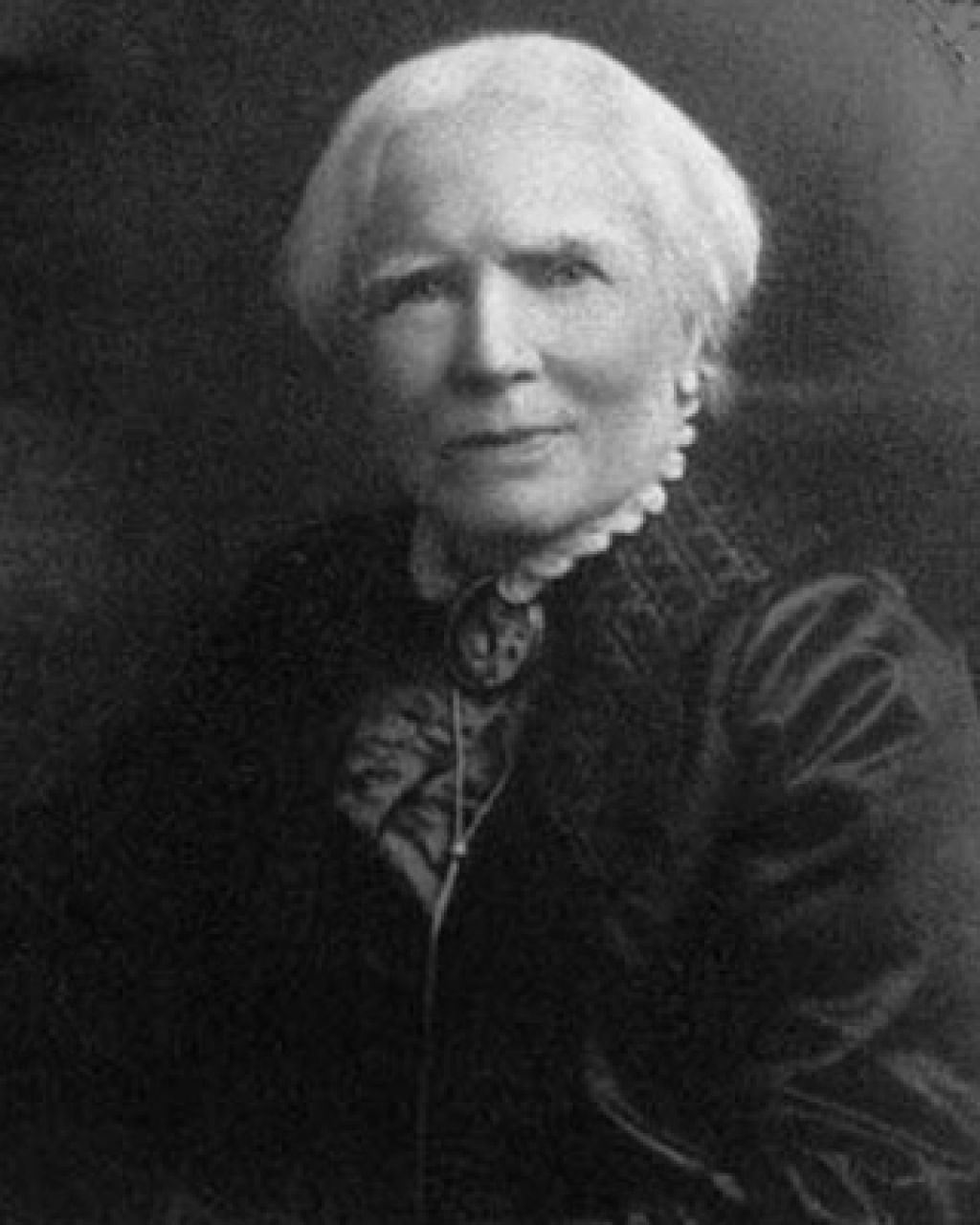

According to Revolutionary War History Buffs, Lydia Darragh was a heroine who saved many lives just prior to Christmas 1777. How did she do it?

Lydia Barrington was born in 1728 in Dublin, Ireland. She married William Darragh, the son of a Quaker clergyman, in 1752, at the age of 24. Three years later, they moved to Philadelphia where Lydia became a nurs-midwife. The family eventually included five children who survived to adulthood.

As Quakers, one would expect that the Darragh’s be typically committed to pacifism. But, each of their grown children helped the patriotic cause. The whole family was also known to promote social reform causes. All members were welcome to speak at meetings, including women. This was quite a revolutionary idea during the 18th century!

Lydia and William’s oldest son, Charles, took his patriotism for the American cause to the next level when he enlisted in the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment. Little did Lydia Darrah know that his enlistment would lead to her becoming the first female American spy.

When British forces occupied Philadelphia in 1777, soldiers would often station soldiers in citizen’s homes. The Darragh residence was one of those homes. Lydia personally appealed to General William Howe to allow the family to stay in the home. She’d already sent the younger ones to stay with relatives and would have no place to go with the older ones.

On her way to meet the General, she met her second cousin, Captain Barrington. He intervened on her behalf and she and the children were allowed to stay in the home. Because Lydia was a Quaker and a woman, she was presumed to be incapable of understanding the intricacies of war.

It was at the Darrah house on the eve of December 2, 1777, that General Howe met with top British officers to plan an attack on Whitemarsh, where General George Washington and his troops were encamped. The family was sent to their bedrooms before the meeting started. With only two days until the planned attack, Lydia hid in a linen closet and took notes. The notes were then concealed in a needle book.

Lydia asked for and received a pass to leave the city to get flour from her cousin. She then took her empty flour sack and notes and left the city. Here is where accounts collide.

US History relates that according to her daughter, Ann, Lydia made her way toward the Rising Sun Tavern, north of the city. It was along the road to the tavern that she came upon Thomas Craig, a man who was in the Pennsylvania militia and knew her son. He took the notes and promised to get them to General Washington.

Encyclopedia Britannica tells us that Lydia listened at a keyhole to the room where the British officers were conferring. On the morning of December 4, she asked for and received a pass to the Frankford Mill. She made her way toward Whitemarsh once away from the city. It was on that road where she met Thomas Craig. After giving him her notes, she went on to the mill and returned home with the flour.

According to his memoir published in 1909, Elias Boudinot, the Commissary of Prisoners, was approached by Lydia Darragh at the tavern. She requested a pass to go to the country to purchase flour. She handed him the needle book. She didn’t wait for him to grant her request before leaving. Once he discovered the rolled-up paper with her notes on it, he rode to American headquarters and relayed Lydia’s notes. The American forces were prepared for the British forces when they showed up at Whitemarsh on December 4.

No matter which story is the absolute truth, Lydia Darragh’s effort as a Revolutionary patriot left its mark on history and today she is regarded as the first female American spy.

And what of the British that fateful day in December? The British spymaster, Major John Andre, questioned Lydia after the meeting and after the British withdrawal from Whitemarsh. He believed her story that everyone was asleep during the meeting. He had this to say when leaving, “One thing is certain, the enemy had notice of our coming, were prepared for us, and we marched back like a parcel of fools. The walls must have ears.”

Recollections salutes American patriots this Independence Day. Take inspiration from Lydia and the clothes she might have worn by browsing our Revolutionary War era dresses and gowns.

Many thanks to Isabell Harkins for researching this topic and providing a first draft.

Thanks for sharing this about Lydia Darragh. I recently found 6 7th great uncles that were Revolutionary soldiers with 1 dying @ the Battle of King’s Mountain. I had already found 1 GGGG grandfather that had fought in the Revolutionary, but after finding the uncles I decided I needed to learn MORE about my heritage!!! This one was short & very good reading. Again Thank you so much for sharing it!!!! Ann R. Shepard