“To the unrefined or unbred, the visiting card is but a trifling and insignificant bit of paper; but to the cultured disciple of social law, it conveys a subtle and unmistakable intelligence. Its texture, style of engraving, and even the hour of leaving it combine to place the stranger, whose name it bears, in a pleasant or a disagreeable attitude even before his manners, conversation, and face have been able to explain his social position.”

~Our Deportment, or the Manner, Conduct and Dress of the Most Refined Society

The Victorian era was a time of strict rules governing social norms and interactions with people outside of one’s family. One heavily honored and heavily regulated custom was that of paying visits to friends. There were elaborate rules in place that determined when a visit was expected, when a visit was appropriate, how the visit should take place, whether time with the head of the household would be expected, and how this time should be used. Prior to the 1800s, handwritten letters were often used to inform of an upcoming visit or left for the head of the household if a visit was made in their absence. As printing became more sophisticated and the custom evolved, calling cards, or “visiting cards” became standard and with them an entire new list of customs and etiquette for use. While business/professional cards also came into use in the 19th century, until the custom of paying visits became less common after the Edwardian era it was not deemed socially appropriate to use a professional card for social purposes.

Do you think you would have enjoyed using the Victorian calling card? Let’s explore the many rules for its use and a bit of what made it fun as well.

What the Victorian calling card looked like

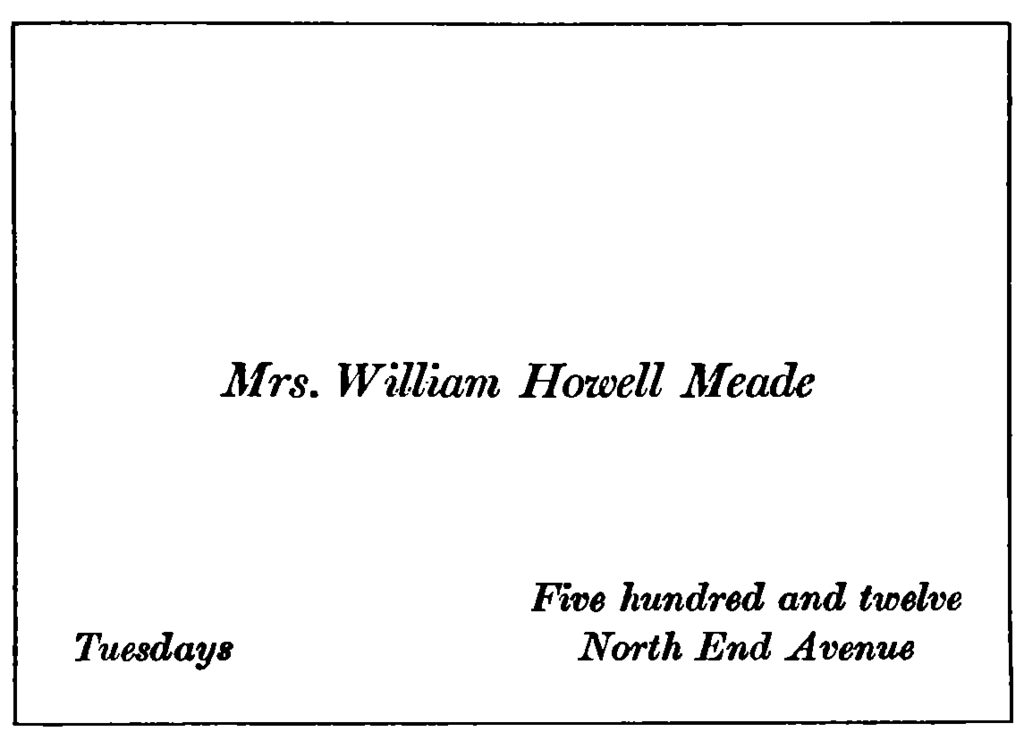

Despite what might come to mind when you think of Victorian stationery, calling cards of the time were meant to be simple and include a person’s name, possibly an address, and for wives, the day of the week they accepted visitors. John H. Young’s Our Deportment, or the Manner, Conduct and Dress of the Most Refined Society, published in 1880 reads:

“A medium sized is in better taste than a very large card for married persons. Cards bearing the name of the husband alone are smaller. The cards of unmarried men should also be small. The engraving in simple writing is preferred, and without flourishes. Nothing in cards can be more commonplace than large printed letters, be the type what is may. Young men should dispense with the “mr.” before their names.”

Also, pass on the gloss finish! “Glazed cards are quite out of fashion.” But the author also points out that trends change rapidly, so this too may change by the next year. Some things never change.

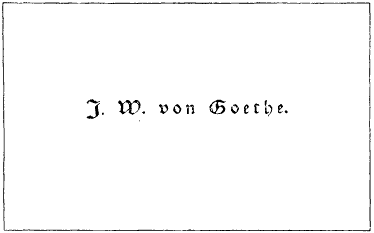

To highlight how simple the Victorian calling card really was, consider that of none other than Goethe below. Clearly even the highest of society kept it nice and simple.

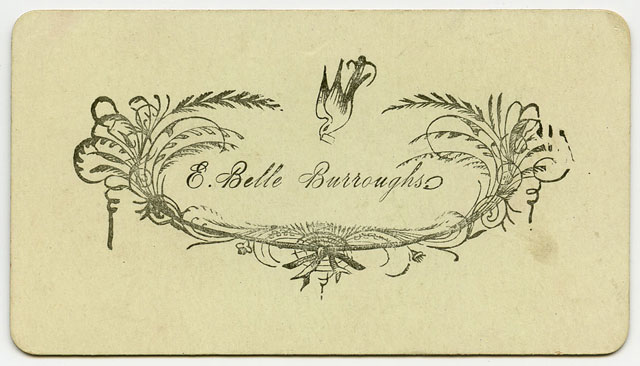

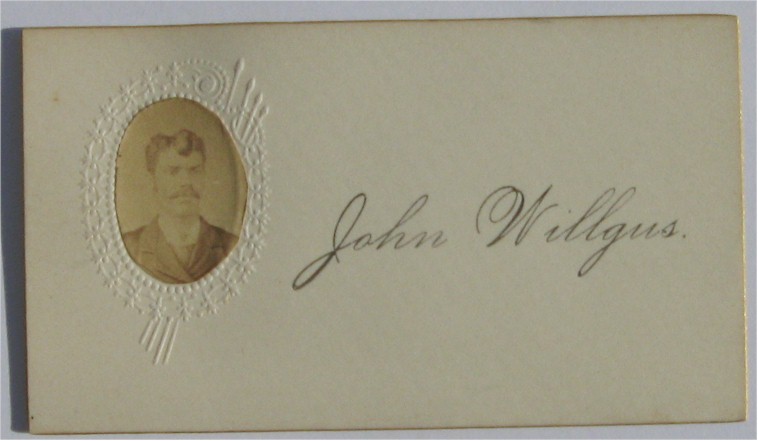

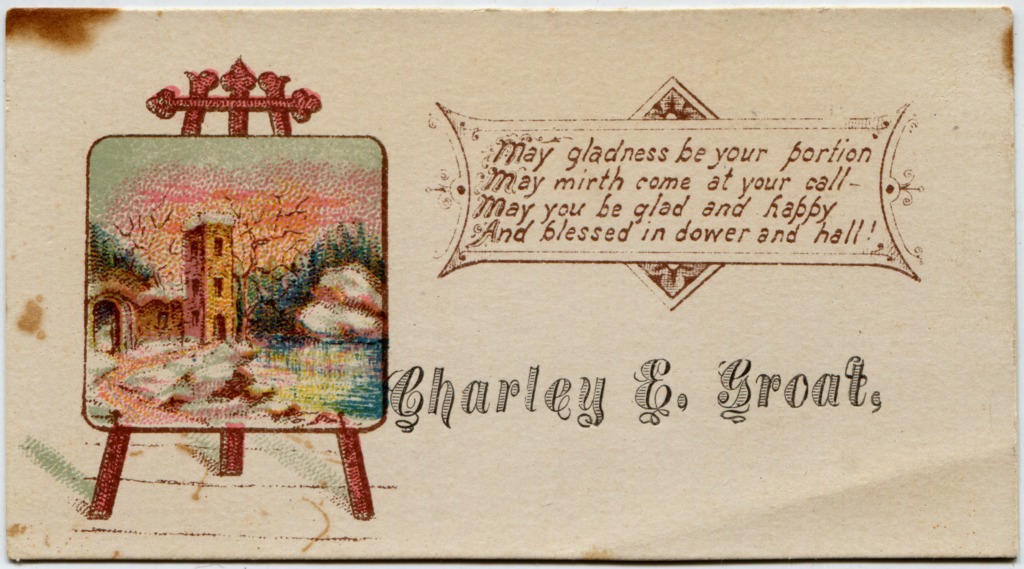

Here are more classic examples of Victorian calling cards:

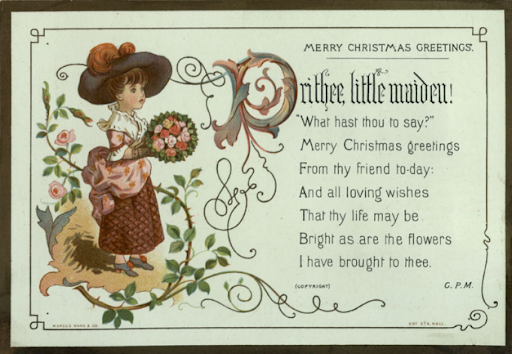

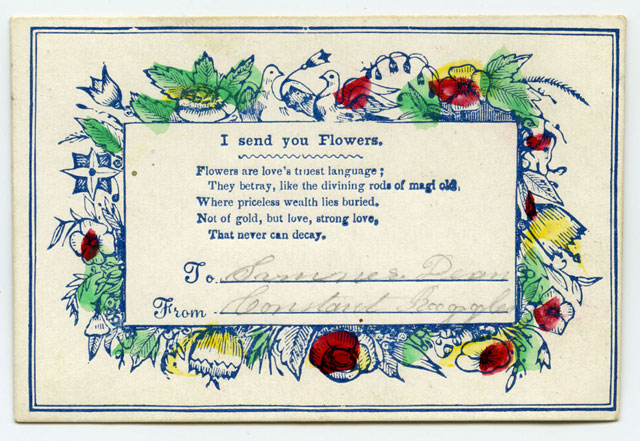

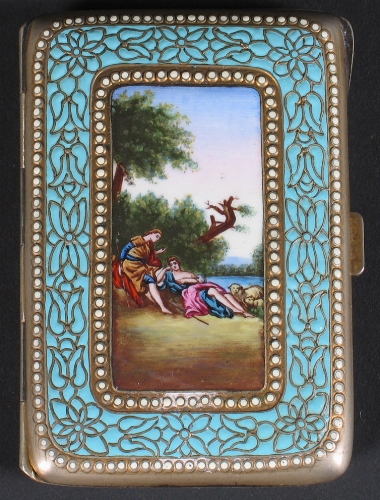

And while you may have seen more elaborate designs such as the one below, these would have been reserved for holidays or other special occasions, not for everyday visits.

Etiquette for using the calling card

Social mores included customs for paying visits that came into play long before one ever entered the home of a friend or acquaintance. For instance, in the late 1800s, it was apparently unspeakable to pay a visit before three o’clock in the afternoon. It was also expected that a call would be made to a neighbor you preferred to stay in good standing within ten days of their move-in. These rules were abundant and specific and I will feature them in a separate post. For now, the rules of the tiny piece of paper will keep us occupied enough.

Etiquette for Americans, published in 1894 lists the following standard when arriving for a visit:

“Put your card in a convenient place in the hall, or on the tray the servant holds out for you, and mention your name to the manservant, if there is one. A man or maid usually takes the card on a tray, and stands holding the curtains (perhaps) aside, for you to enter, speaking your name audibly at the same time. Sending or taking the card in before you to the drawing-room on “afternoons,” is obsolete.

Men were expected to do the same, except to always leave their walking stick and hat in the receiving room.

It was not always assumed that a caller would be received and a lot of the etiquette revolved around the act of simply leaving the card, with a lot implied with just that act. Therefore, an elaborate system came into use in which the one leaving the card would utilize the corners of the card to convey various messages to the mistress of the household. Some of these included:

- A congratulatory visit: the left-hand upper corner

- A condolence visit: the left hand lower corner

- Taking leave (if you were going on a long trip): right hand lower corner

- If there were two or more ladies in the household, the gentleman turned down a corner of the card to indicate that the call was designed for the whole family.

By the end of the 1800s, the custom of folding the corners had gone out of custom, though leaving cards upon arriving for a visit would remain a custom for another couple of decades.

There was also an entirely separate list of implications around sending or leaving a calling card in an envelope, such as expressing a lack of interest in a gentleman caller.

Caller be careful

My favorite bit of advice from the Victorian etiquette manuals around calling cards is the warning against attempting to make a friend look good by also leaving their card when placing a call to someone who turns out not to be available. This seemingly innocent act could turn into a major Victorian faux pas. Etiquette for Americans reads:

“Leaving other people’s cards is a rather precarious business, and done at the caller’s risk! It is not pleasant to meet your hostess driving in just as you sail out with the consciousness of having done a good stroke for a friend. In case the returning householder makes inquiries, and finds only one visit has been paid, there may be no particular harm done; but that depends upon the sensitivities of the lady.”

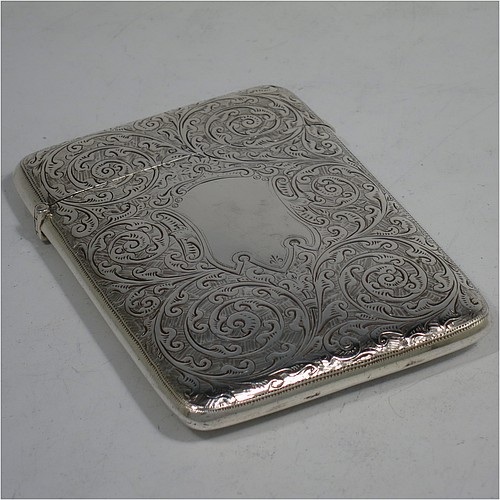

Victorian calling cards also came along with some very pretty accessories

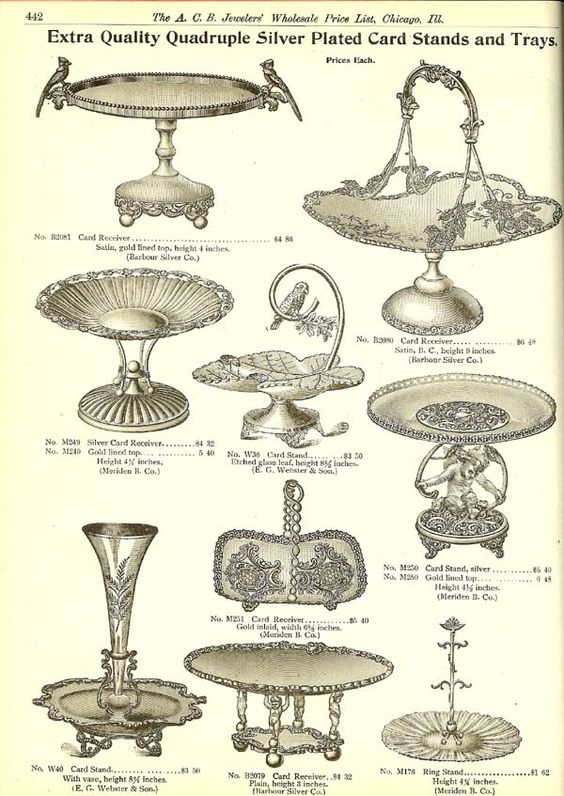

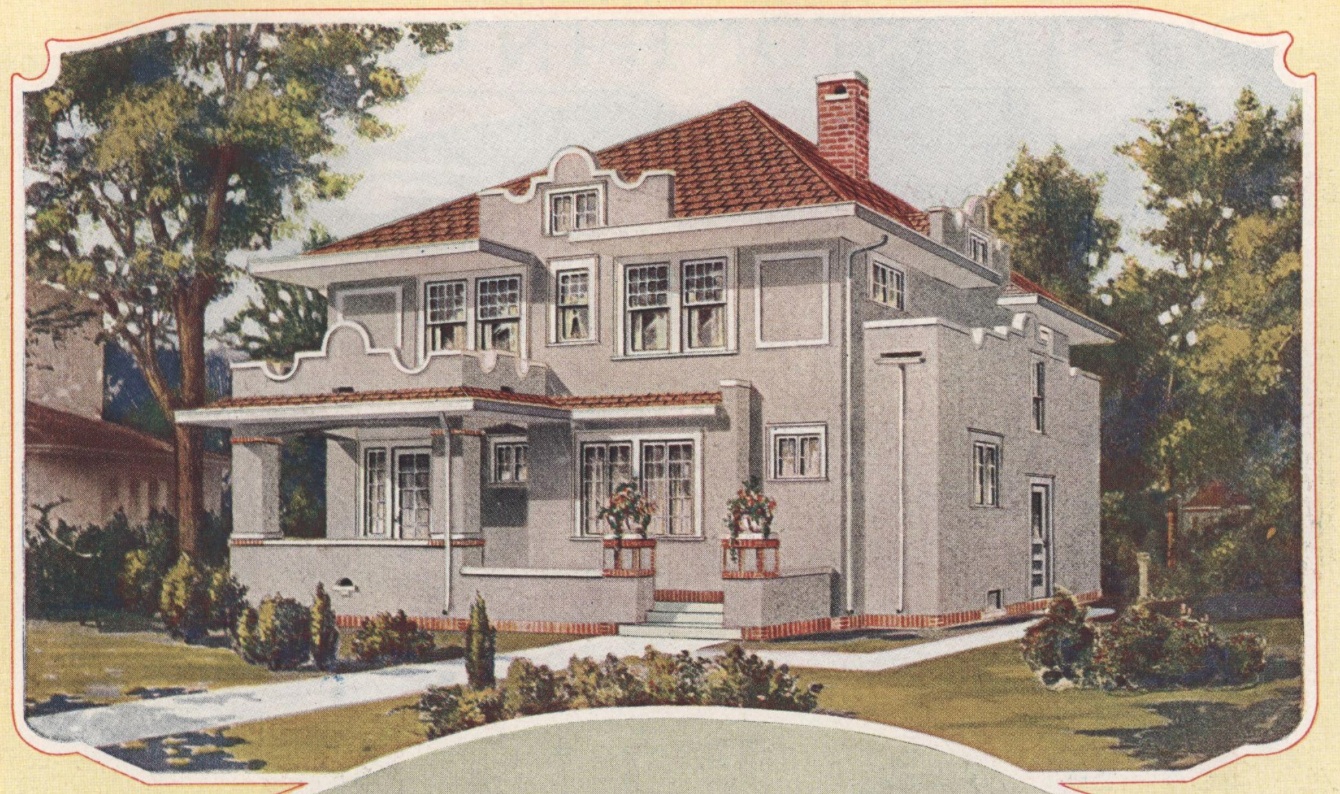

As seen above, when entering a home to pay a visit, one’s card would be left either on a tray or with a member of the household staff. These trays said a lot about the status of the household and were absolutely lovely items.

Plus, men and women alike got to carry their cards around in these charming and intricate little cases.

Should we bring the custom of making calls back?

With the emergence of the telephone, a world war, and general societal change, the act of calling became a thing of the past and so did calling cards. As I sit here writing months into a pandemic and in a year that I’ve spent largely alone, it is not hard to imagine how fun an afternoon of visitors might be, however. While text messaging may always be preferred to popping in unannounced, maybe this is one Victorian tradition we should bring back in one form or another.

Featured image: 5 O’Clock Tea by David Comba Adamson (1859-1926)

[…] Calling cards were often elaborately designed, with intricate engravings and elegant fonts. They served as a form of social currency, indicating one’s place in society and connections. The exchange of calling cards was a highly ritualized process, with specific rules about when and how to leave them. For example, a folded corner on the card could indicate that the visit was intended to be brief. […]

I wish there were any easy way to print this article. I would like to keep it for future reference.

I carry some 🙂 They are handy sorta like a business card name and ph. or I can write on them.

I think it would be quite lovely and fun!