Spring is here and summer is fast approaching. While 2020 might not include family reunions, street festivals, and out of state vacations, there is still the opportunity to get out safely and enjoy nature. My own COVID-19 schedule includes daily walks in my Denver neighborhood with various exercise routines at a local park. As I often do, I have recently been thinking about how women would have enjoyed the outdoors before we possessed so many freedoms. What I have learned is that the ability women have today to benefit from exercise and recreation outdoors was far from an organic evolution. As with most areas where women have seen gains, it only became acceptable for women to engage in various outdoor activities after daring, pioneering women paved the way. Here are the stories of three early women’s outdoor clubs and the determined women who founded them.

Nature Calls: Cora Eaton and the Mountaineers

I have been familiar with the story of Cora Smith Eaton and the Mountaineers Club since reading Why They Marched as part of my book club this year. Many of you will be pleased to learn that this story includes women who were pioneers in both the political arena and athletic arena, as founding members were dedicated suffragists.

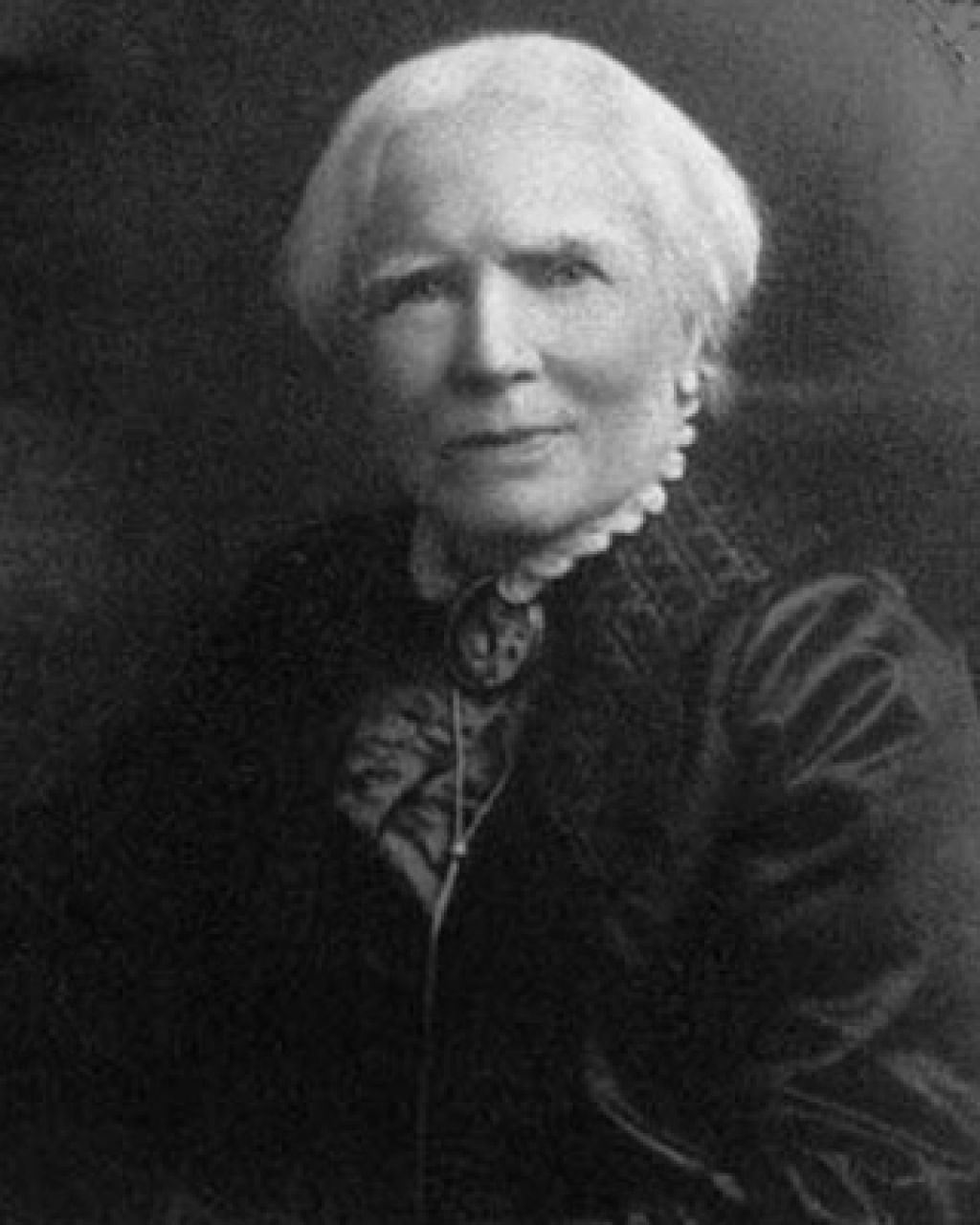

Dr. Cora Smith Eaton was the first woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of North Dakota, beginning her practice in 1892 after graduating from Boston University School of Medicine. She eventually moved to Washington and established a practice, along with developing a love of hiking and camping. While I am unsure of how this interest began, in 1906 she became one of the founding members of The Mountaineers hiking club. Remarkably for the time, its membership consisted of 77 women and 74 men.

Many of the women involved in the suffrage movement understood the way that personal and political liberties overlapped. Besides advocating for the vote, women became involved in dress reform, advocated for freedom of travel, pushed for greater educational opportunities, promoted birth control, and took up pastimes never before pursued by their sex. Cora hoped to see more opportunities for women to enjoy the great outdoors. When the 41st annual National American Women Suffrage Association convention was held in Seattle in 1909, Cora Smith Eaton jumped at the chance to combine her passion for suffrage with her passion for hiking and introduce more women to the pursuit.

photo from nps.gov

Cora Smith Eaton organized a Mountaineers-sponsored “side-trip” to hike Mount Rainer from July 17 to August 7. While the more well-known women of the movement declined to participate, once the group reached the summit, Cora planted her “Votes for Women” banner.

Given that nearly everything I have read on the subject includes discussions on the challenge clothing presented to women hiking during this time, I imagine it was a true dilemma. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, women were still expected to wear skirts. The December 1887 issue of Appalachia included detailed instructions on acceptable women’s hiking attire that included both a knee-length skirt as well as an ankle-length skirt, both of heavy materials. A corset was considered optional. By the early 1900s a complete 180 had taken place, with skirts being banned by the Mountaineers. Sourcing knickerbockers would still remain an issue for several years, resulting in such recreational activity being enjoyed primarily by the upper class.

Road Warriors: Motor Maids

After Amelia Earhart achieved her dream of flying, she quickly sought to encourage and support other women to do the same. She founded The Ninety-Nines, a club for female aviators. The club did more than get women up in the clouds, it encouraged other females with extreme-sports ambitions to band together. Enter the Motor Maids of America, North America’s first women’s motorcycle club.

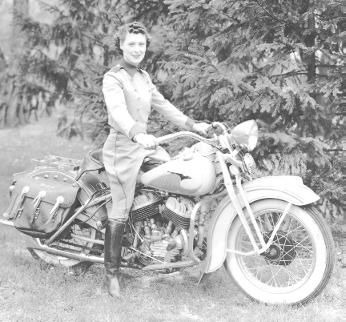

Founded by Dot Robinson and Linda Dugeau in 1941, the mission of the club was two-fold. First, provide a social space for like-minded women to connect while also advocating for safer roads and street practices.

The 1940s was a touchy time for women to be taking to the road without a male chaperone, on or off a motorcycle. Besides safety concerns, there was also the assumption that female riders were of loose moral character or simply “unladylike.” The initial approach was to combat potential discrimination by having members wear pink uniforms and white gloves at club events. The uniform was changed to blue and silver by 1950, but to maintain the respectability of the group, applicants were put through an extensive background check and a three-month probation period before becoming official members.

To reinforce their desired image, the club involved itself with various charitable causes, but to me, the most important thing they did was to open the doors for the expansion of what was considered an acceptable arena for women at the time. It wasn’t long before members Adeline and Augusta Van Buren became the first women to ride across the United States by motorcycle. Linda Dugeau used her talent as a rider to embark on a career as a courier and an off-road tour guide. Dot Robinson became the owner of a Harley Davidson dealership spent the rest of her life as the poster woman for a woman’s ability to be “respectable” and enjoy less-than-conventional past times.

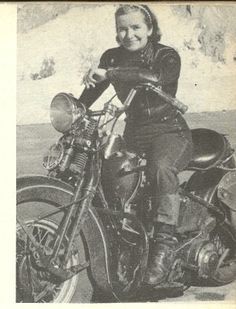

While not a member, in the 1950s Bessie Stringfield would shock onlookers by traveling the country on her motorcycle, becoming the first African American woman to ride cross-country solo. Besides performing in festivals around the country, regardless of Jim Crow laws, she was also one of the few civilian motorcycle couriers during WWI and the only female. Today, the American Motorcyclists Association awards extraordinary female riders with a medal in her name.

The Motor Maids is still thriving today, with 1,300 members across the United States and Canada.

Huddle! British Women’s Football Club

Nettie Honeyball had a vision. She desired women to be seen as full, capable human beings. Not, as she said, as the “‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured.” In 1894, she decided to be proactive about making change. Her means: football. She placed ads in newspapers and by the next year had organized the British Women’s Football Club.

To say that Honeyball and the British Women’s Football Club faced resistance would be an understatement. 45 years before the Motor Maids tried to downplay their actions with pink uniforms and gloves, players appeared in public wearing clothing that made physical activity possible and shocked the nation. When she appeared in her first newspaper interview Honeyball sent Victorian ladies reaching for their smelling salts as she was proudly photographed in a long-sleeved shirt, shorts, long socks, and chin guards.

Public games were organized and played, but the English public was slow to catch on. Although 10,000 people showed up to the first match on Easter Sunday, 1895, after taking a look, many got up to leave, and newspapers mocked the players, focusing largely on their uniforms.

Honeyball and the other players persevered, embarking on a tour around the country, jeers aside. When they attempted to bring the trend to Scotland, however, violent onlookers prevented games from taking place, and women’s football struggled to stay alive. That was, of course, until World War I.

As with World War II, the first war found women staffing factories and taking a larger than normal role in maintaining society, culture, and spirits at home. It wasn’t long before factories began organizing female football leagues, likely in the absence of organized sports with so many men away. This time, the public came out in support of the female players. One Boxing Day match in 1920 was watched by 53,000 people in the stands.

But the popularity would be short-lived. The end of the war brought women being shuffled back into homes and asked to accept a pre-war lifestyle. In 1921 the Football Association banned women’s games from taking place on any grounds used by member clubs, effectively removing them altogether. The ban stayed in effect until 1971, at which point women entered the sport in enormous numbers. Today, women’s football (or soccer as it is known in the United States) is a popular sport worldwide, with championships being televised throughout the world.

What is your favorite outdoor activity? Have you ever looked into the history of women in participating? Let me know and your activity might end up in a follow-up post.

For further reading:

How the Bicycle Brought 19th Century Women Freedom

Leave A Comment