It may seem highly modern, but did you know that Victorians enjoyed home workouts? Women especially were encouraged to exercise at home, petticoats and all.

I have gone digging and have uncovered several early exercise manuals for women. They reveal a lot about 19th-century culture, and attitudes on health and women. Plus, they are quite amusing. I also enjoyed taking a look at some of the similarities between how we exercise today and also how drastically things have changed. Some of the highly-praised calisthenic exercises, for instance, would today seem useless for health, and some downright injurious.

Let’s take a look at the 19th century home workout and how people stayed in shape in simpler times.

Let not the ladies be idle

The 19th-century saw an enormous evolution in attitudes and opinions on how middle and upper-class women should be spending their time and everyone wanted to make their input known. I think that it would have been a stressful time to navigate life as a woman. On the one hand; parents, preachers, public figures, and the media were quick to criticize women for anything perceived as silly or idle. And on the other hand; pastimes and activities were highly prescribed. There was a small window of options for acceptable pursuits. The expert opinion on female exercise of the time is the perfect example.

Walkers Exercises for Ladies is one of the earlier exercise manuals from the 19th-century that I came across. Published in the 1830s, Donald Walker sought to rid the world of sedentary ladies and present options for exercise that was both intentional and appealing to women. One of the reasons being is that when left to their own devices, they could hardly be trusted to pursue activity with any health benefits:

“The only exercises, indeed, to which, in their hours of relaxation, young ladies have access, are in general only a few insignificant games, or amusements extremely limited, from the nature of the space afforded for the purposes of exercise. Even these are in general carefuelly prohibited as soon as the pupils enter into them with ardour and perhaps properly so; for exercise indulged in without any regulation might produce real inconveniences, which a system composed of select exercises, suited to the age and strength of the pupil, does not produce.”

In addition to providing descriptions of the emerging calisthenics, Walker also provided information on proper posture and the correct way to perform daily activities such as standing and writing.

The American Woman’s Home, published in 1869, shows exactly the type of double-bind women could be put in, for it criticized exercise for exercise sake at the same time that it encouraged women to get plenty of movement and be mindful of their physical health:

“…it is far better to trust to useful domestic exercises at home than to send a young person out to walk for the mere purpose of exercise. Young girls can seldom be made to realize the value of health, and the need of exercise to secure it, so as to feel much interest in walking abroad, when they have no other object. But, if they are brought up to minister to the comfort and enjoyment of themselves and others, by performing domestic duties, they will constantly be interested and cheered in their exercise by the feeling of usefulness and the consciousness of having performed their duty.”

The dancing debate

There were, naturally, many references to dancing in the 19-century manuals on exercise that I read. Here again, we see a wide range of opinions. We may think today that dancing in the 19-century was an innocent activity that people, especially Victorians, couldn’t get enough of, there were actually a lot of skeptics.

A Treatise on Domestic Economy, written in 1868 by Catherine Beecher, included long chapters on proper exercise and looking after one’s health. But one activity Miss Beecher would not provide her stamp of approval to was dancing:

“The writer was once inclined to the common opinion, that dancing was harmless, and might be properly regulated; and she allowed a fair trial to be made, under her auspices, by its advocates. The result was, a full conviction, that it secured no good effect, which could not be better gained another way; that it involved the most pernicious evils to health, character, and happiness; and that those parents were wise, who brought up their children with the full understanding that they were neither to learn nor practise the art…Those young ladies, who are brought up with less exciting recreations, are uniformly likely to be the most contented and most useful.”

And those who had been allowed to indulge in dance? “Comparatively tasteless.”

The Utility of Exercise, a Calisthenics manual from the 1820s, said that dancing was a timeless pursuit of the gods:

“Independently of the salutary effects arising from the kind of exercise just mentioned, much benefit may also be derived from dancing. The ancients celebrated much the exercise of dancing. They said it was invented by the goddess Rhea; and it has been approved of by the greatest men of all ages.”

Calisthenics for ladies

It seems that all experts of the time could agree on one thing: calisthenics was where it was at. Believed to be derived from two Greek words meaning “strength” and “beauty,” the stationary strength exercises would dominate the fitness world for over a hundred years and still remain present today.

Catherine Beecher herself is credited with being one of the first influencers to popularize calisthenics. And while Walker’s book pre-dates her 1856 Physiology and Calisthenics, the later appears to have taken off much more with the general public.

Calisthenics for Ladies, published in 1831 (again pre-dating Catherine Beecher’s book) beautifully outlines the idealogy behind promoting the exercises for women:

The purpose of calisthenics:

- They bring every part of the system into action.

- Expand the chest.

- Bring down the shoulders.

- Make the form erect.

- Give grace to motion.

- Increase muscular strength.

- Give a light elastic step in walking.

- Restore the distorted or weakened members of the system.

- Prevent tight lacing.

- Promote cheerfulness.

- Render the mind more active.

- They are conducive to general health.

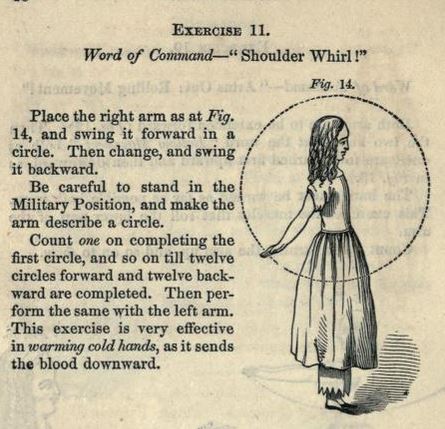

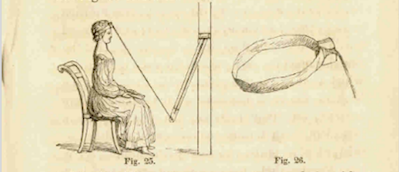

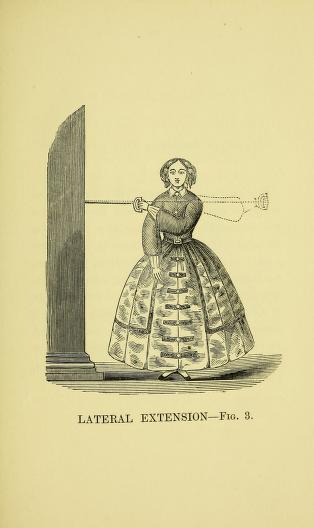

The many manuals published over the next several decades included illustrations of the exercises along with a description. Take, for instance, the entry below.

FIG 25

“The girl, as you see, sits in a chair, with the band around her head, and pulls up the spring. You will say, perhaps, that it looks a little Irish, to pull the head down to keep it up, for this is in fact the mode employed; the spring acts with a great deal of force to return to its place; in order to prevent this, the head must be held very straight, and the muscles of the neck and shoulders are thus brought into vigorous exertion. Habitual crookedness is often occasioned by the weakness of those muscles.”

And then again, not all manuals had illustrations for each move. A Treatise on Calisthentic Exercises by Marian Mason included a handful of illustrations at the back of the book, but some were to be performed merely with the aid of the descriptions. One of the author’s “Complicated exercises in place” reads:

“The pupil must place herself with the heels on a linen bending both arms, the elbow as high as the shoulders, the forefingers placed on them, and extend the right arm sideways and on a line with the shoulder, bringing at the same time the leg to the right, the knee stretched, the toes pointing to the ground; she must then return to the first position, bringing the right heel close to the left, and do the same with the leg and arm, then with the right and left alternately, and lastly with both together.”

Now you try!

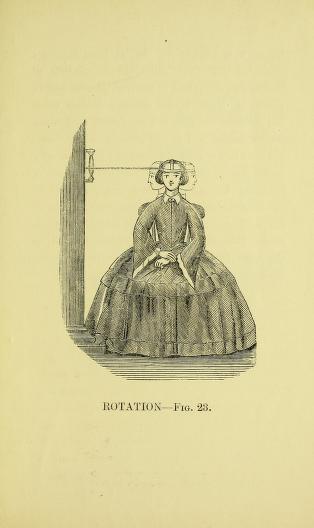

The Victorian home gym

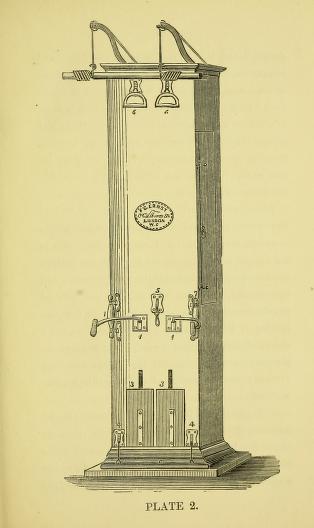

One of the things that surprised me the most about this topic was that a book titled The Portable Gymnasium from 1861 was all about how to use an exercise machine that actually looks quite a bit like the ones still used today, and certainly with the same functionality.

The author, Gustav Ernst, openly and enthusiastically states in the intro that the machine is meant to be used just as much by women as by men. He also states that while it may be an expense, the machine is a practical investment considering the cost of public gyms (this also surprised me) and the inconvenience of leaving the house:

“In an economical point of view it all, where there are several members in a family, repay itself in less than six months, if the expenses incurred by using a public Gymnasium are considered; for though it may be needed for restoration in a case of spinal deflection, or less of muscular power, it will afford to the younger branches of families, in town or country, such salutary amusement as may rank with useful occupation when unfavorable weather or other circumstances preclude out-door exercise.”

So willing was Ernst to promote the book to all that half of the illustrations are of women performing the exercises. What do you think of their workout clothes?

You may also enjoy:

How crazy was the bicycle craze?

Leave A Comment