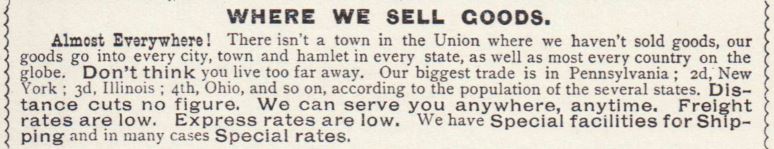

You might think that you can purchase any and all things you might be able to think of through your Amazon Prime app. A hundred a fifty years ago this is what people were thinking as they turned the pages of the recent Sears catalog. But instead of a few taps, sought-after items were requested through the mail and patiently hoped for over a period of weeks or months. And those who made such purchases counted their blessings. Mail-order catalogs changed the way that women and families consumed goods and maintained their homes while changing the American retail landscape.

Besides allowing rural households access to affordable goods (well over half of the popular lived in rural America when Montgomery Ward launched the first catalog), mail-order shopping increased women’s power as a consumer, a dynamic that exists in homes to this day. The successful companies were industrial and commercial miracles of their time. Let’s take a look at the history of this form of frontier window shopping.

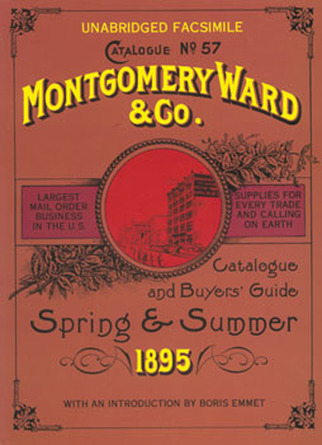

Montgomery Ward

Chicago was one of the top industrial centers in the mid to late 1800s and is where Aaron Montgomery Ward began his mail-order catalog empire. Legend has it that as a young man he tried his hand at door-to-door sales, gaining an understanding of rural life and how families sourced goods. He learned that products sold in general goods stores were often marked up so high that most people struggled to purchase them. And this was assuming that the man responsible for such decisions was able to make the trip to the store.

Ward was a man with a plan. He landed in Chicago in 1872 and set to work to become a direct supplier to the public, allowing them to purchase goods without the markup. And this is my favorite part: the now-famous catalog began as one sheet of paper selling 163 items and including steps on how to order.

It was far from an overnight success. Ward dealt with failed business partner relationships, strong opposition from store owners, and enormous difficulties shipping items. But it was a sound plan with a huge target audience. To help put the minds of the sometimes skeptical public at ease, he was an early adopter of the “money-back guarantee” that the catalogs of the time would become so known for.

By 1883 one page and 163 items had turned into 200 pages with over 10,000 items. Montgomery Ward was at the top of the food chain, but another enterprising man was about to amp up the competition.

Montgomery Ward fun fact: Rudolf the Red Nose Reindeer was originally a part of a marketing campaign put on by the retailer after it evolved into storefronts.

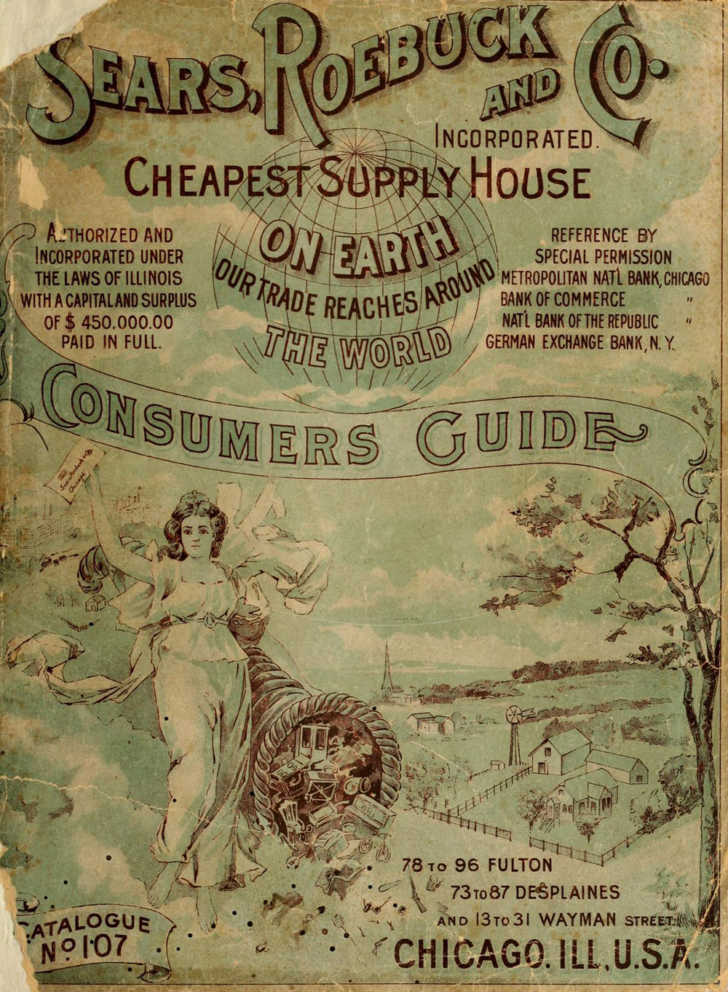

Enter Sears

The story of Sears is another great lore of Americana. This one involves the growing railroad, a bag of watches, a lift-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps mentality, and big claims that went along with a belief in the importance of one’s word.

Richard Sears was as American as they come. The son of a blacksmith and wagon-maker, he began work for a railroad as a young man, heading from Minnesota to the west.

This is where the story typically begins on most blog posts you will read about Sears. Somehow the young man came into possession of a box of watches. Some sources say that the box was delivered to the station for which he was working and was left unclaimed. Others claim he befriended a young man who was unsuccessfully attempting to sell the watches, prompting Sears to buy them at cost. Whatever the case, he soon learned the potential of selling directly to customers and in his ability as a salesperson.

Sears successfully continued to sell watches up and down the railroad line, learning as he went. He began using flyers to advertise and is said to have been a copywriting genius from the beginning. With suitcases full of cash, he made his own way to Chicago in 1887 with his sights set on expansion.

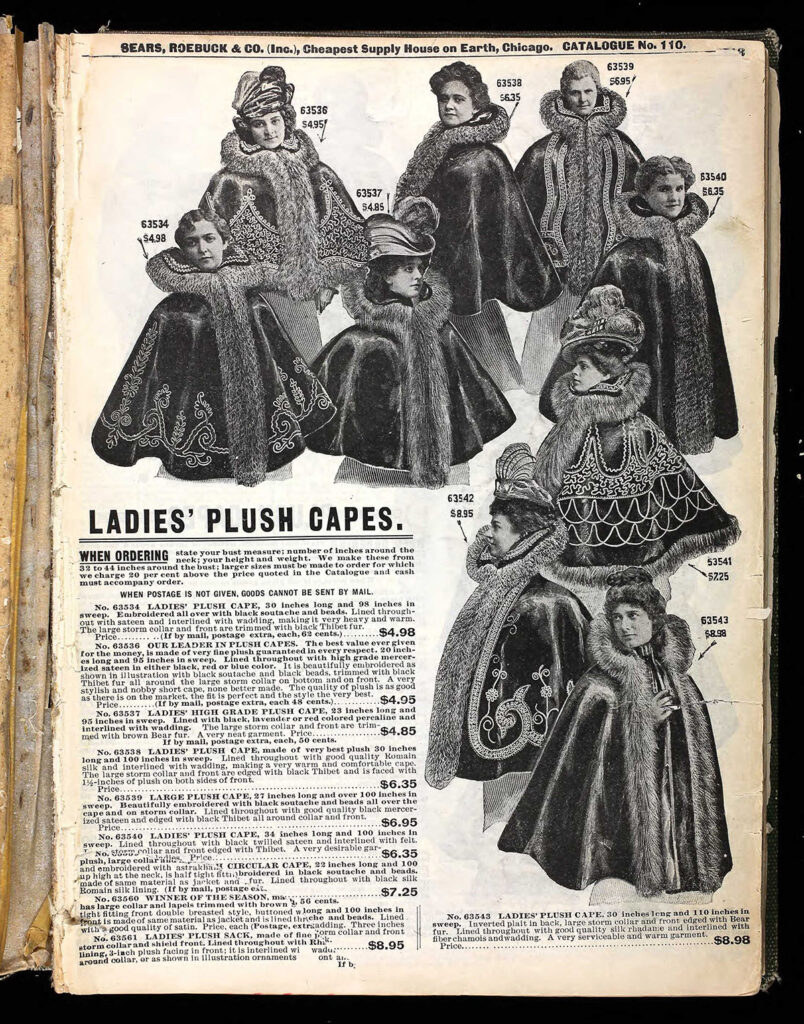

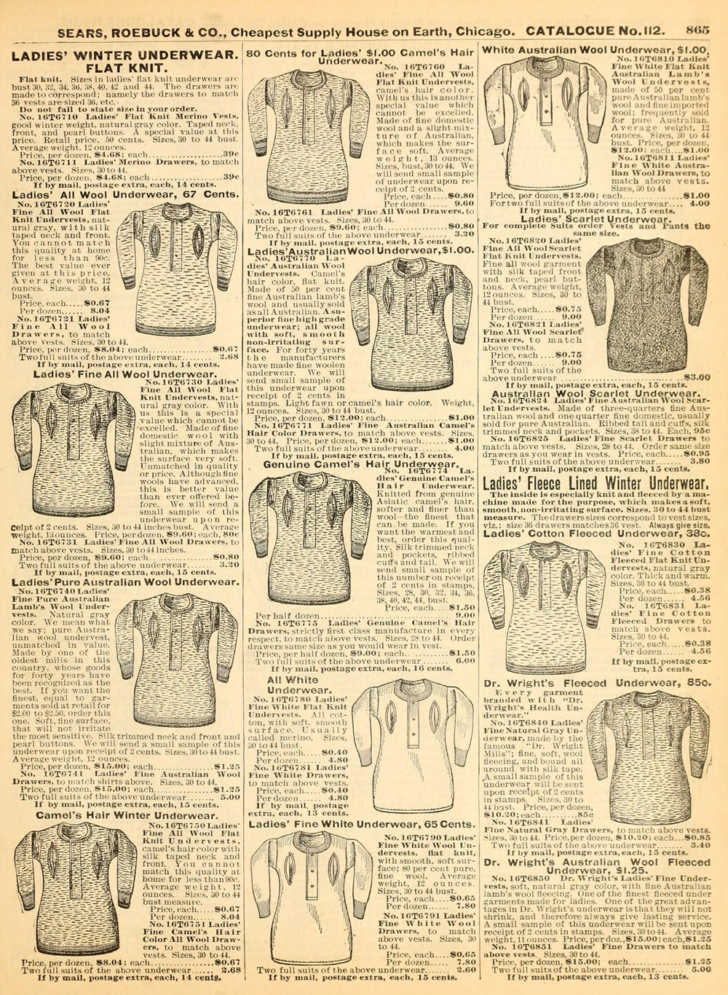

Sears became a watch mogul. The company evolved into selling exclusively by catalog in 1893. This led swiftly to mail-order catalogs also offering clothing and leisure items in 1897, and then to dominate the industry for almost a hundred years after.

Sears fun fact: Richard Sears was a childhood friend of Alonzo Wilder, wife of reader favorite Laura Ingalls Wilder.

What couldn’t you buy in a mail-order catalog?

Aaron Montgomery Ward and Richard Sears took their ingenuity into the American world of retail at the most optimal time possible. The industrial age was a force that could not be reckoned with and the amount of “stuff” and the amount of desire for it was a tsunami sweeping the states. I’m not sure what was happening with more speed, manufacturing or buying.

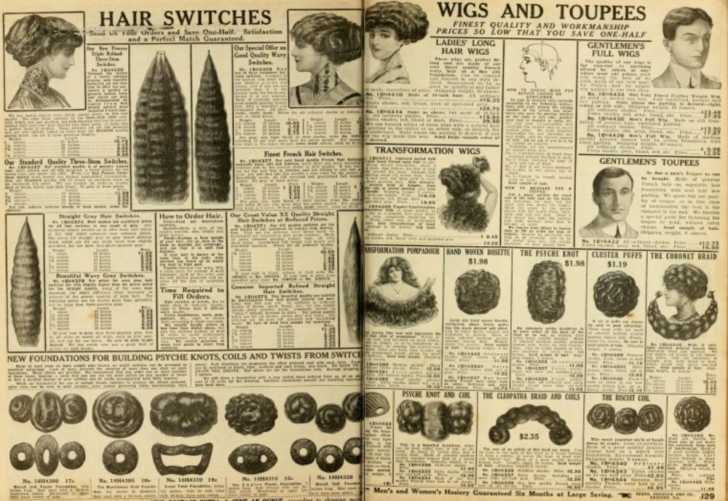

While the mail-order catalogs started off modestly, they didn’t stay that way. And sadly, I can’t think of anything better to company them to than Amazon Prime, as they were truly known to have any imaginable good available. And for a low price. We’re talking tens of thousands of products, all in the pages of a print catalog. Some of these items may come as a surprise to you. Here’s a list to wake up your curiosity:

Corsets

Organs

Wagons

Pills for impotence

Bust cream

Firearms

Baby chicks

Tincture of opium

Women’s and men’s hairpieces (often made of human hair)

Sweaters with silk breast pockets (had anyone ever seen this before???)

Chastity belts and belts meant to improve male sexual performance

Stockings

Curtains

Maternity corsets

Cribs

And much, much more

But wait…there’s more. How about a mail-order catalog house?

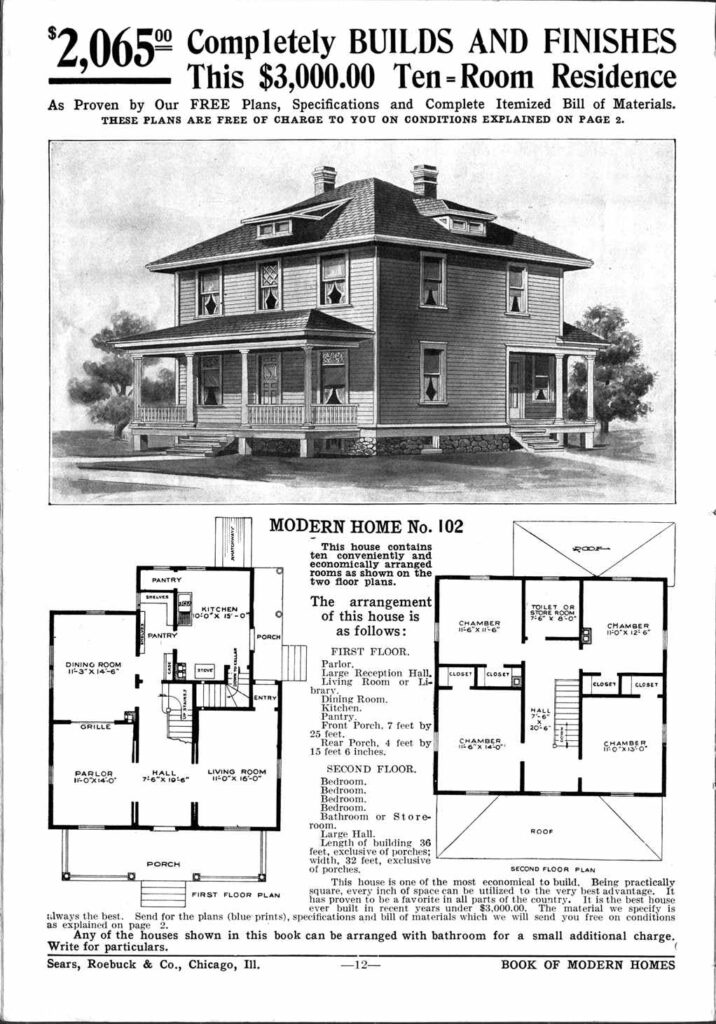

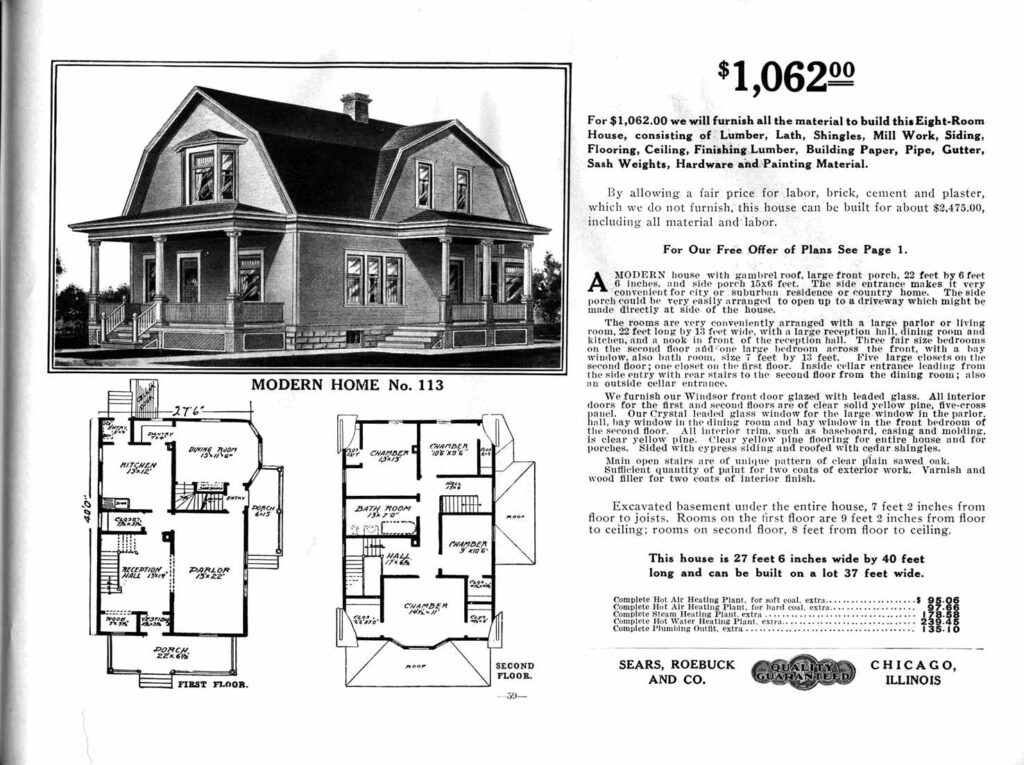

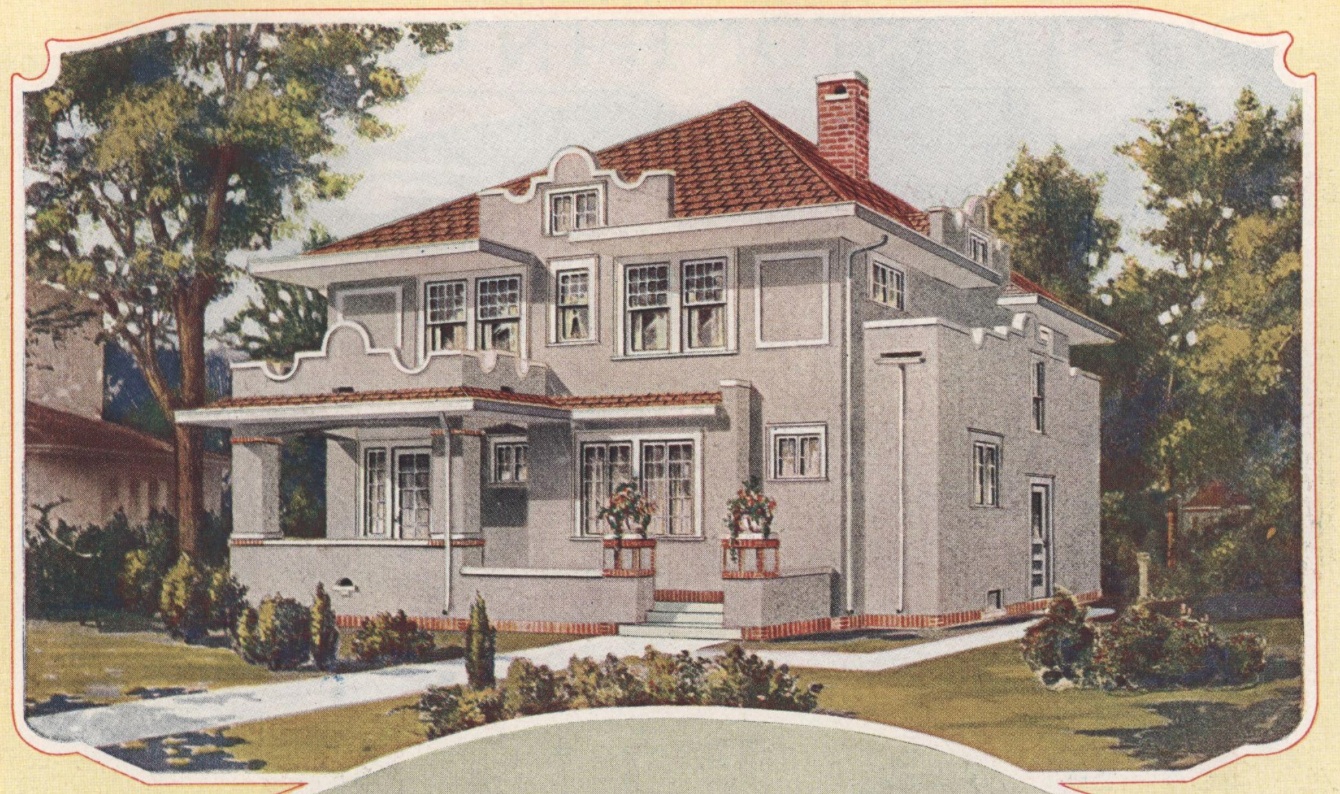

When you picture the portrait of the American dream, what you see? Pop culture has been successful in forcing many of us to land on a magazine spread that includes a modest but spacious house with a lovely lawn and of course, a white picket fence. Well, many people must have had the same idea by the 1900s, because Sears decided to start selling DIY home construction kits in 1908.

This is truly remarkable. Until 1940, a family could buy everything needed to build a house, from easy-to-follow instructions to the fixtures. Says NPR:

“The Sears Modern Homes catalog debuted in 1908, and it offered all the material and blueprints needed to build a house. The pieces that arrived in the mail were meant to fit together sort of like Legos, so buyers could build the houses themselves or hire contractors. “

NPR says that from 1908 to 1940 roughly 70,000 such homes were purchased. And what’s even more remarkable is that it is estimated that 70% still stand today.

A personal touch

I enjoyed reading about the attention to customer service that the early mail-order catalogs provided. From a marketing standpoint, the priority of serving the consumer was front and center:

The policy of our house is to supply the consumer everything on which we can save him money, goods that can be delivered at your door anywhere in the United States for less money than they can be procured from your local dealer, and although our line covers about everything the consumer uses, there is scarcely an article but what will admit saving of at least 15 per cent and from that to 75 per cent, to say nothing of the fact that our goods are as a rule of a higher grade than those carried by the average retailer or catalogue house, and we earnestly believe a careful comparison will convince you that we sell more goods and of better value than you could obtain for the same money from any other establishment in the United States.

Historic Catalogs of Sears, Roebuck and Co. Spring 1896

And the early catalogs sought to practice what they preached. Aaron Montgomery Ward was known to respond personally to letters and encouraged correspondence between customers and staff. And according to Country Living, Sears implemented the same attention to detail, ensuring that notes from customers would be answered:

“Although Richard Warren Sears was not known for sending out the letters that Ward did, Sears insisted his employees handwrite notes instead of using a typewriter—some customers were offended to receive a letter that came from a machine…

In their return letters, employees offered congratulations for marriages, the arrival of a new baby, or a condolence for the loss of a family member. These messages had meaning for many customers, and some even sent letters thanking employees for their support…

Customers gave updates on their lives and even explained why they hadn’t ordered in a while. One farmer wrote to Mr. Ward, detailing why he hadn’t made a purchase since the previous fall catalog: “Well, the cow kicked my arm and broke it and besides my wife was sick, and there was the doctor bill. But now, thank God, that is paid and we are all well again, and we have a fine baby boy, and please send plush bonnet number 29d8077…”

Montgomery Ward took such pride in their customer service that they shared the letters in their team newsletter:

Eatons, the successful Canadian mail-order catalog, started off with a similar emphasis on the personal touch. Says Virtual Museum:

“Eaton’s understood that many people were not used to ordering clothing by mail sight unseen. The catalogue assured its out-of-town customers that not only would they get quality goods at the cheapest prices, but in the latest fashion: “A staff of young ladies with excellent judgment in matters of dress go, your letter in hand, until your entire order is filled, and give distant purchasers the benefit of a thorough knowledge of the most advanced fashions. They can shop for you better than you can yourself.”

The proliferation of wife-by-mail led to many a homesteader requesting such a service, but that is a post for another time!

You may also enjoy:

Before fashion magazines, there were fashion dolls

Heck even in 1981 you could order from a Sears Catalog.

I so appreciate this! For two and a half years I ran a Montgomery Ward Catalog store in Wantage, NJ, which is quite a rural area at the top of the State. Wards had moved it’s main warehouse for my area from Albany, NY to Baltimore, Md which proved to be a poor decision. The mail order catalog business soon ceased for Montgomery Ward. My little store was literally two small room in the back of my house. Customers would call in their orders which I would submit to the company. Twice a week, I would receive the merchandise and call the customers to let them know their orders were ready for pick up. I got to know so many local people I’d not know before. One even turned out to be my Congressman! That was during the Cabbage Patch Kid craze, and I am happy to report that despite many “Ship Later” notices, every single customer received their Cabbage Patch Kid in time for Christmas that year! As I recall, those Kid orders were over $50,000.00 that year. I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

The expansion of railway service across the western part of the continental US, together with regular mail service enabled Sears and Montgomery Ward to reach customers who would otherwise have been completely isolated in the West. In many ways, the railroad was the 19th century equivalent of the internet, in enabling all kinds of service providers that would have been impossible to difficult previously, when it took six months to cross from Missouri to California or Oregon by ox wagon, and maybe a year to get a letter from the west to the east coast.

Love it! Kinda miss catalogs really. It was so exciting to read the description and place the order then wait in anticipation until at last it arrived 🙂 Also, the Levi Straus house in SF is a Sears house. What fun to venture down this memory. Thank you.