Paisley prints are among the most popular here at Recollections, and certainly around the world and through time. The pattern is so popular that it is easy to take it for granted as just sort of always been around without putting much thought into how it became so ubiquitous. At least, that is how I have always thought of it. I was recently asked to look into the background of this dainty yet striking symbol and discovered a history of something I never knew had a history.

Before you put on your next paisley print shirt or shawl make sure you read on for plenty of conversation starters about this ancient and present pattern.

Origins of the paisley design

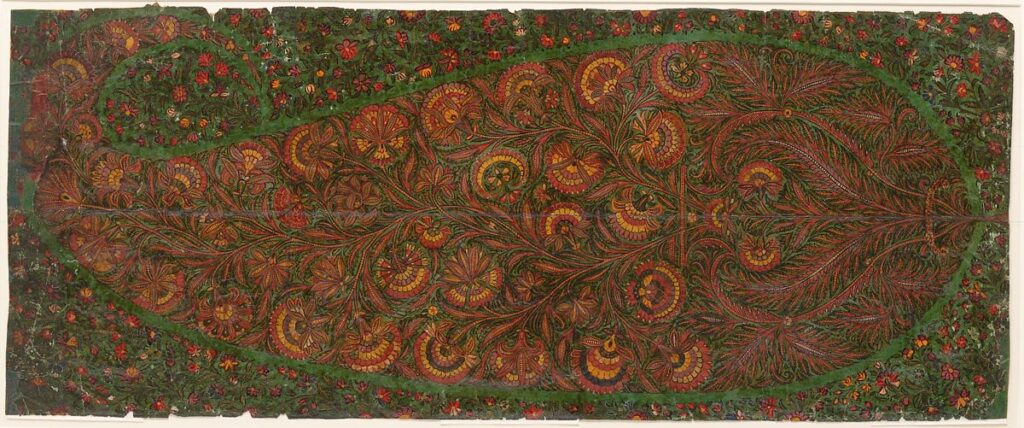

It is hard to identify the precise emergence of the paisley design, but it is possible to get close. According to fashion history scholars it is first seen in images from the Persian Empire in around 221 AD, though I have seen estimates much older. What do you think the pattern most symbolizes? In researching for this post I saw it used to describe a general floral design, a part of a flower, a tadpole, feathers, the ying-yang symbol, and mangos. We may never know what the earliest users of the pattern had in mind, but it is obviously something that humans strongly relate to as it is one of the most enduring symbols of all time.

Kashmir, India

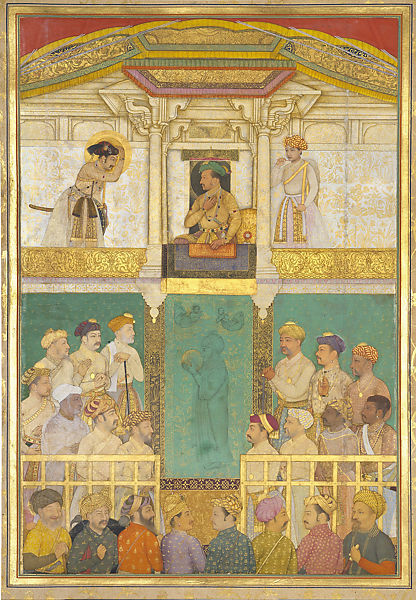

Paisley would eventually achieve worldwide affection because of its use on shawls, which derived from its use on the sashes of wealthy and royal men. The first imagery depicting this style is found in the 11th century, though it would rapidly pick up in the 1400s with the rule of Zain-ul-Abidin in the Kasmir region of India. Zain-ul-Abidin had a passion for weaving and would work hard to make his city known far and wide as the ultimate producer of textiles in the world.

It was not just marketing that allowed Kashmir to dominate the textiles scene but the elaborate use of a very specific type of goat hair. Says Slate.com:

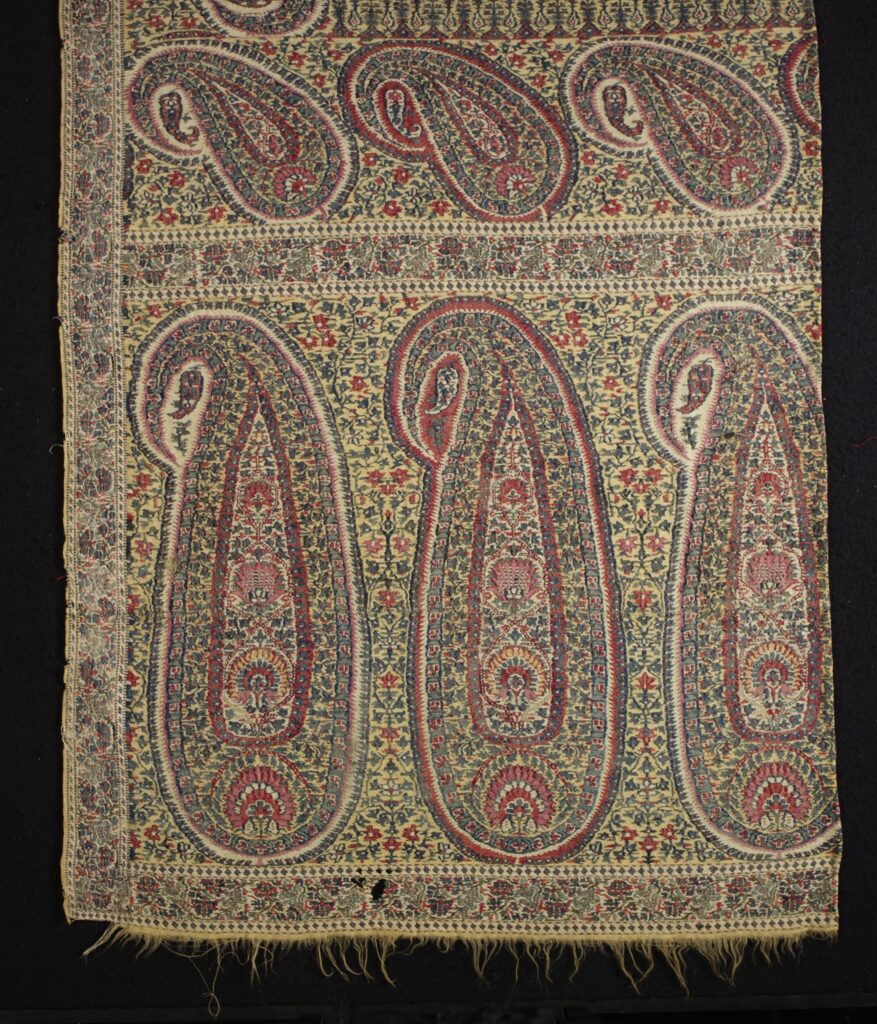

“there was nothing efficient about making a Kashmiri shawl. Its wool came ?from a Central Asian species of goat, Capra hircus in Latin?or shahtoosh in indigenous terms. These animals wandered into the high Himalayas, where the bitter cold made their underbellies sprout a dense, ultrafine wool. The goats shed this pashmina, as this wool was called, in the summer by rubbing themselves against rocks and bushes; textile workers then literally climbed the Himalayas, collected the fluff by hand, and spun it into thread.”

The paisley pattern was always one of the most popular patterns in Kashmir shawls, though the term “paisley” would not come into use for many years. Because of the laborious process of weaving, the paisley pattern is seen primarily on the edges of sashes and shawls (as opposed to the entire piece) from the 15th-17th centuries, but widely so. Shawls from Kashmir were exported all throughout Asia and the Middle East for centuries, and would eventually be found on the European continent, changing the history of textiles and the paisley forever.

Napoleon

Of course, the East India Trading Company played a large role in the rapid and massive interest Europeans had in Kashmir textiles. The company also played a role in the general accessibility of the Asian continent to Europeans, allowing certain individuals to become highly influential in the spread of the craze as well. One of these individuals was Napoleon himself.

Napoleon’s wife Josephine was well known for her love of the paisley pattern and shawls in general. It was her husband’s expeditions that first led her to develop this love and add an enormous amount of fuel to the shawl fever spreading in France and England.

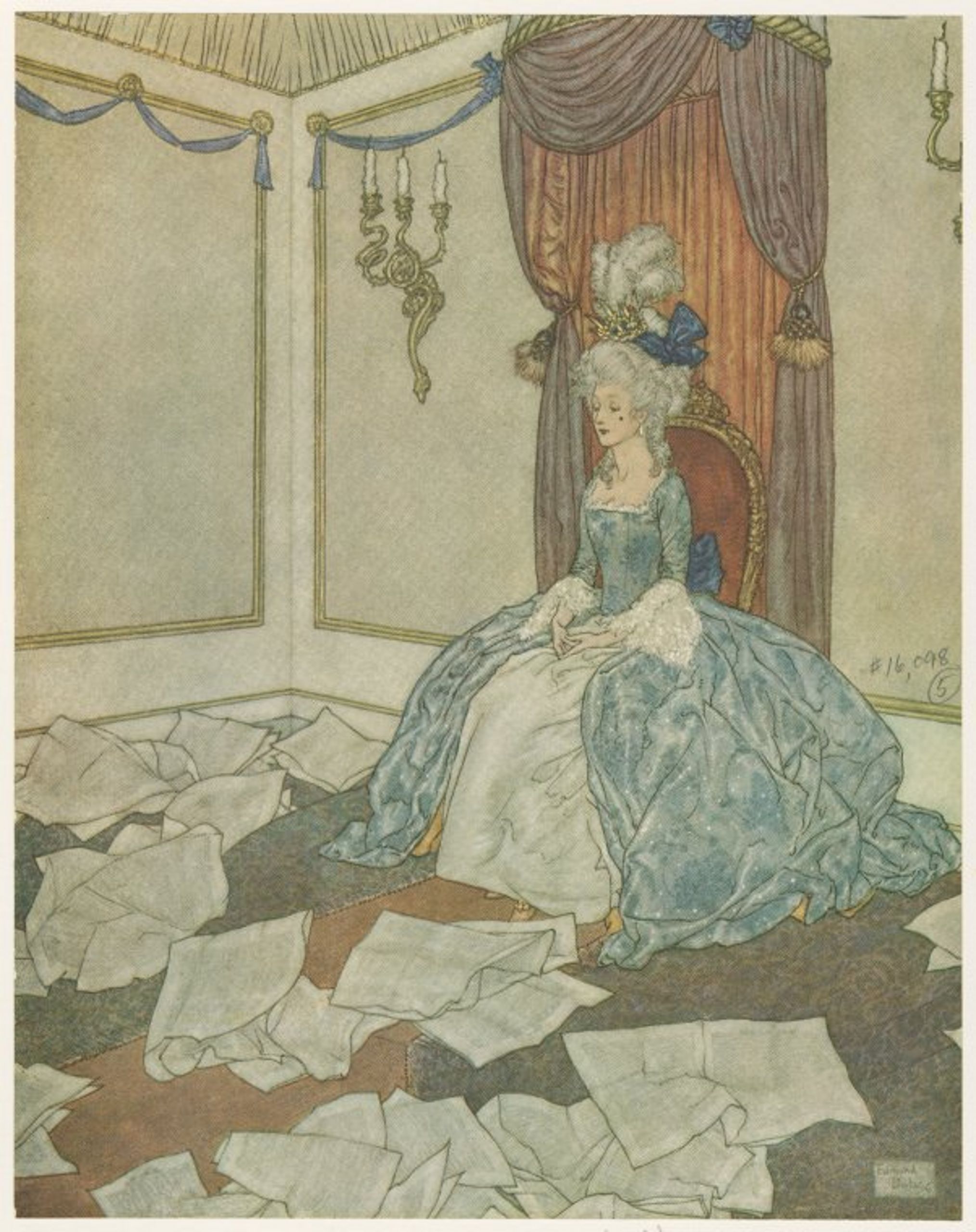

As I mentioned earlier, Kashmir exported its shawls around Asia and the Middle East, and certainly, there were many other regions where textile manufacturing took place. When Napoleon was completing his Egyptian campaign in 1789 he was so impressed with the shawls he saw that he brought back plenty for Josephine to enjoy. And enjoy them she did. At the time of her death, there were 45 shawls in her wardrobe, and she had many more made into dresses as the years went by. Because of her influence as a trendsetter, she is considered to have started the craze and likely did. We can easily see how this would have happened, as multiple paintings of her include her paisley shawls.

After the beginning of the 19th century Europeans, especially the British, could not export Indian shawls, especially paisley shawls from Kashmir, quick enough.

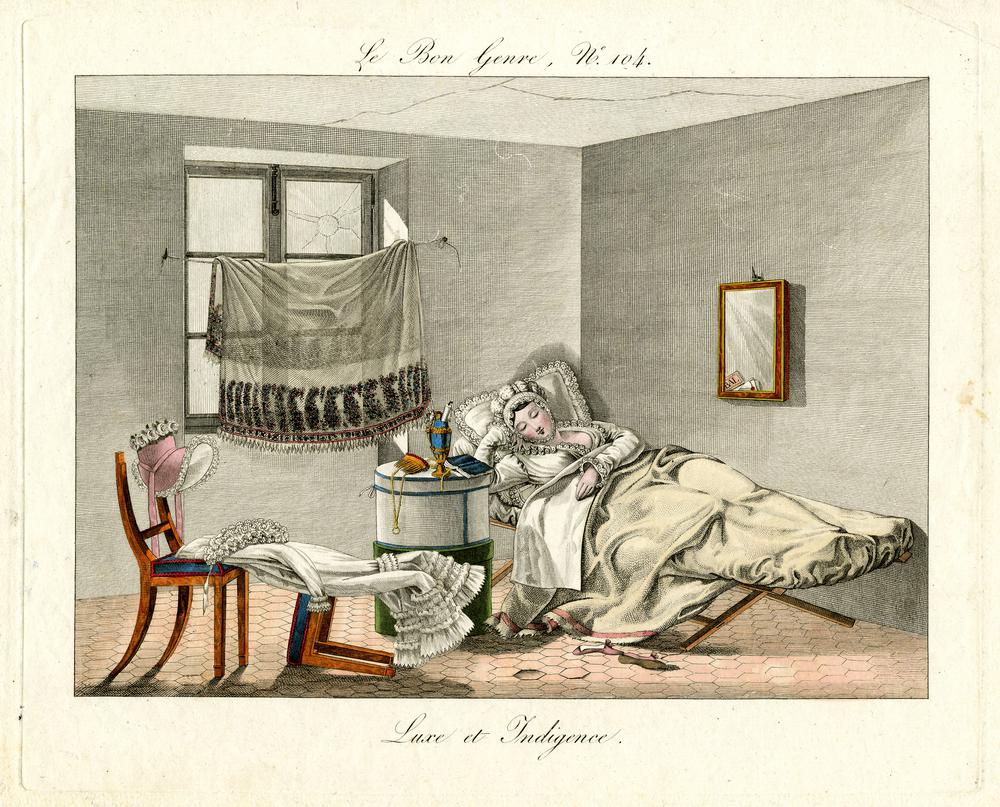

According to curator Melinda Watt, because of the high quality of the Kashmir technique and the fact that they were imported, they became status symbols similar to a handbag today. In her presentation “From Kashmir to Paisley: Excerpts from a Textile’s Journey” Watt points out her favorite fashion plate, Luxe et indigence from the 19th-century French magazine Le Bon Genre. The 1817 plate depicts a woman living in the lowest of circumstances but surrounded by fine fashion goods, including a fine shawl covering her window. The fashion plate is a cheeky look inside what was prioritized by women during this time, or at least what they were perceived to have prioritized.

Paisey shawls would soon become more widely available and thus easier to afford, in Europe, however, with the help of a determined Englishman.

William Moorcroft

William Moorcroft was born in 1767 and lived a life interesting enough for his own post. An illegitimate child in a time very hostile to them, he would eventually go on to be the first Englishman to complete formal training as a veterinarian, traveling to France to do so. He would then build a large-livestock practice before leaving to become a ‘superintendent of stud’ for the East India Trading Company. A lot of the information about him online centers on his extensive travels and involvement with foreign relations. What is less known about his life is his involvement in the establishment of textile manufacturing in England.

When Moorcroft went on his first expedition with the East India Company in 1808 he traveled to Bengal and would go on to travel the continent, including a trip across the Himilayas in 1812. It was during these trips that he developed a love of Kashmir shawls, especially the paisley pattern. His goal was to bring Kashmir designs and the Kashmir technique back to England.

As Watts points out, Moorcroft’s first attempt would be a “Very poor but typically perhaps very Victorian way.” Remember what I said about the Kashmir technique and the use of very specific goat hair? Well, the explorer gathered goats onto a boat and set out to bring the industry to England. With male goats on one ship and females on the other, his plan was in place. Sadly, the entire thing would be foiled when a shipwreck cause the deaths of the female goats.

For his second attempt, Moorcroft decided to commission Indian textiles designers to create designs that he would have produced in England. 34 of them remain in museums today. This would prove to be much more successful and would come at exactly the right time as well, as use of the Jacquard loom was expanding to meet the demand for shawls.

Enter Paisley, Scotland

Paisley, Scotland was already a center for textile manufacturing before the Kashmir craze truly took off, but it was only able to survive due to interest in woven textiles, as it had previously produced silk goods, which were falling out of fashion. In the early 1800s Paisley native, Thomas Coats saw the opportunity that shifting to integrate with the Kashmir trend presented worked to transform it into a thread and weaving town. While the shawls produced were of a style distinguishable to the fine shawls of Kashmir, the infrastructure was in place that allowed Paisley to quickly become the textile capitol of the world for a time.

It was not until this time that the pattern would finally become known as “paisley” because of the world’s association with Paisley with the shawls.

The paisley pattern is here to stay

While the shawl craze would petter off due to a variety of reasons, the paisley was in the western world to stay, as seen in the following images of paisley patterned dresses.

Do you have any paisley in your wardrobe?

More fashion history fun:

A short history of the hand muff, one of history’s cutest accessories

Elegance at Home: Victorian Wrappers

Leave A Comment