Frances Perkins – “I am extraordinarily the product of my grandmother”

Frances Perkins was born Fanny Coralie Perkins. She was born on April 10, 1880, in Boston, Massachusetts. Her parents were born in Maine and although the family eventually settled in Worcester, their roots were firmly planted in Newcastle, Maine.

Fanny spent her childhood summers with her grandmother, Cynthia Otis Perkins, on the family farm in Newcastle. It was here where she would gain wisdom at her grandmother’s knee; wisdom that would guide her throughout her life. She referred to her grandmother as “an extremely wise woman – worldly-wise, as well as spiritually wise.”

Fanny’s family roots in America reached back to the 1750s when her father’s family settled in Newcastle. Cynthia’s mother, Thankful Otis, spent her final years in Newcastle with her daughter. She passed down many stories that gave Fanny a deep appreciation for not only her family’s patriot ancestry but also history in general.

Young women in the late 1800s didn’t often attend college but Fanny was groomed for higher education. Her father taught her to read at an early age and taught her Greek grammar when she was only eight years old. Her interest in classical literature was encouraged. Upon graduation from Worcester’s Classical High School, Fanny entered Mount Holyoke College, the oldest continuing institution of higher education for women in the United States.

The philosophy of Mount Holyoke’s founder, Mary Lyon, was “education was to fit one to do good.” She encouraged women to take on the responsibility education required of them and to “go where no one else will go, do what no one else will do.” It was this sense of purpose and a class in American economic history that would shape Fanny’s future.

When first confronted with poverty as a young school girl, she was given the standard answer of the day: poverty was the result of alcohol or laziness. When confronted with poverty and the working conditions many women and children had to endure through the coursework in her class, she was “horrified at the work that many women and children had to do in factories.

There were absolutely no effective laws that regulated the number of hours women and children were permitted to work. There were no provisions which guarded their health nor adequately looked after their compensation in case of injury…” She took on the mantle of doing whatever she could to help affect change. Her commitment to change was solidified by a speech by Florence Kelley, executive secretary of the National Consumers League, in 1902.

Fanny was raised in the Congregational Church but after moving to the Chicago area to teach, she became an Episcopalian and changed her name to Frances. Her faith would provide strength commitment throughout her adult life.

Frances Perkins spent her free time working at Chicago Commons and Hull House. Time spent with the tenants of these settlement houses allowed her to see the effects of poverty and convinced her to take the path she would follow the rest of her life.

She moved to Pennsylvania in 1907 to work as general secretary of the Philadelphia Research Protective Association. Its mission was to help prevent newly arrived immigrant girls, including those from the South, from working as prostitutes. She confronted pimps and drug dealers during her investigation of phony employment agencies During this time, she also studied sociology and economics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Frances earned a fellowship with the New York School of Philanthropy in 1909 where she investigated childhood malnutrition among school children who attended Public School 51 and lived in the city’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. This led to her enrolling at Columbia University to pursue a master’s degree in sociology and economics. Her thesis was based on the research she did during her fellowship.

The following year brought Frances Perkins full-circle with Florence Kelley, whose speech set the course of her career. She became the Executive Secretary of the New York City Consumers League, working directly with Florence Kelley. Frances continued her work through the league. She promoted the need for sanitary regulations for bakeries, fire protection for factories, and limiting the number of hours women and children could work to 54 per week. She spent much time in Albany, lobbying for change.

Her life was forever changed on March 25, 1911. After hearing fire engines while having tea with friends, Frances ran to the scene to find the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s top three floors engulfed in flames. She watched in horror as 47 workers, most of whom were young women, jumped to their deaths. The fire claimed 146 lives that day. The seeds of the New Deal were planted that fateful day.

When the citizens’ Committee on Safety was formed to prevent this tragedy from recurring, Theodore Roosevelt suggested Frances Perkins be hired as the executive secretary. When the committee’s mandate broadened, Frances’ experience and expertise resulted in the most comprehensive workplace health and safety legislation in the nation.

Not long after women were granted the right to vote in New York in 1918, Frances Perkins was appointed to a vacant seat on the New York State Industrial Commission. The appointment made her the first woman to hold an administrative position in the state’s government and made her the highest paid woman to hold public office in the nation. Her annual salary was $8,000.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected governor of New York in 1928, he asked Frances Perkins to be the Industrial Commission, overseeing the whole labor department. She called out the Hoover administration in 1930 for lying to the American people about rising employment and recovery from the Great Depression. Unemployment was actually rising, and people were running out of resources. She used her position to explore long-range options to increase employment and ultimately, an unemployment insurance program.

Frances left public service in New York for service at the national level when Roosevelt was elected president in 1932. She was tapped to be in the newly-elected president’s cabinet, serving as Secretary of Labor, the first woman to serve in this capacity. The policy priorities she set forth included a 40-hour work week, legislation regarding worker’s compensation and minimum wage, unemployment compensation, the abolition of child labor, and Social Security.

During this time, she also spent one day each month in spiritual renewal at an Episcopal convent in Cantonsville, Maryland. She would also return to Newcastle to recover and renew each summer.

Frances Perkins left the Department of labor in June 1945 following Roosevelt’s death in April. On her last day, she personally thanked and shook the hand of each of the department’s 1800 employees. She followed her time at the White House with what many consider to be the definitive biography of FDR, The Roosevelt I Knew.

President Truman appointed her to the United States Civil Service Commission in 1947. She left public service in 1953 and started a new career that included teaching, writing, and public lectures. She was a lecturer at Cornell University’s School of Industrial Relations at the time of her death from a stroke on May 14, 1965. She is buried beside her husband, Paul Wilson, in her beloved Newcastle.

Part of her legacy is the Frances Perkins Program at Mount Holyoke. The program is designed for women of non-traditional age who wish to complete a Bachelor of Arts degree.

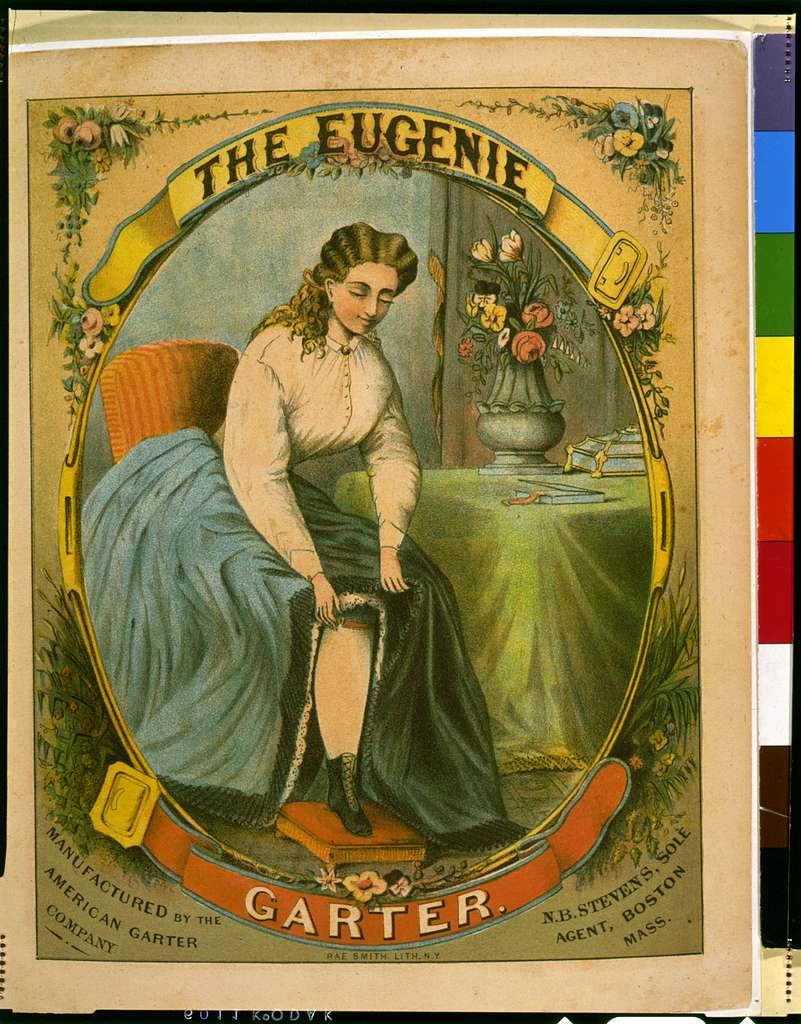

As a designer and manufacturer of history-inspired fashions, we’re inspired by women who have made history. We hope you enjoyed a glimpse into this history-making woman’s life. Here are a few examples of Recollections clothing inspired by Frances Perkins’ early life during the Edwardian era.

Credits

Sprague, Leah W. “Her Life: The Woman Behind the New Deal.” Frances Perkins Center. 1 June 2014. francesperkinscenter.org/life-new/.

Cash, Chris. “Frances and Faith: Introduction.” Frances Perkins Center. 17 January 2018. http://francesperkinscenter.org/frances-and-faith-introduction/

Breitman, Jessica. “Honoring the Achievements of FDR’s Secretary of Labor.” Frances Perkins – FDR Presidential Library & Museum. https://fdrlibrary.org/perkins

Perkins, F. Frances Perkins. Biography. A&E Television Networks. 27 February 2018 https://www.biography.com/people/frances-perkins-9437840

Thank you for your kind comments, Geri. We’re very happy you and your husband enjoyed these amazing women! — Donna

Both my husband and I have totally enjoyed the inspiring articles during Women’s History Month. I would read them aloud to my husband over the breakfast and dinner table. They don’t teach this stuff in school unless one takes an elective class on such. Thank you for sharing such great stories about those women who fought for social justice for women and children, and for Americans in general.

Thank you for featuring one of my all time heroes. Very few people, especially women, know of her extraordinary work and the she is responsible for bringing the minimum wage and overtime to the workers of America as well as social security.

Thank you for yet another inspiring story to mark Women’s History Month. Indeed, every month is a nod to the perseverance and ingenuity of womanhood! What a blessing to count ourselves among these heroic trailblazers! An inspiration that even the smallest effort on our part is like the pebble tossed into the pond- the ripples spread beyond us! Your website is an inspiration as well, the clothes are beautiful, well made, and transport us to another time! Thanks for all you do to keep history alive!!