Episode two of A Very British Romance covers love in the Victorian era and it did not disappoint! It was so full of great information and charming stories about coupling in the 19th century that I was disappointed when I realized the end credits were rolling! The docuseries’ premise is that all of the courtship rituals that we take for granted today had to be invented and that many of the roots can be traced to fairly modern times. In this episode, host Lucy Worsley walks viewers through some Victorian courtship practices that still survive today and a few that stayed behind. I love that I learned a few fun things about one of my favorite eras! Here is a handful of my favorites.

The language of flowers

In the Victorian era, sending flowers was much more than a traditional romantic gesture, it was a way for men to communicate specific sentiments to the object of the gift. Floriography, i.e. the language of flowers, became a very hot industry, with manuals listing the meanings of individual flowers and combinations of flowers common household items. I was particularly excited about this aspect of the documentary as I recently bought a copy of Secret Meanings of Flowers by Brenda Jenkins Kleager and have been meaning to dive into it.

As I mentioned, bouquets had very specific meanings pointing to the regard a gentleman had for his love. A bouquet of strawberry, mignonette, bluebell, and tulips, for instance, spoke to the character of a woman and meant to communicate “your perfect goodness, excellent qualities, and kindness constrain me to declare my regard.” Violet, jasmine, and roses, on the other hand, meant “your modesty and amiability inspire me with the warmest affection.” Swoon!

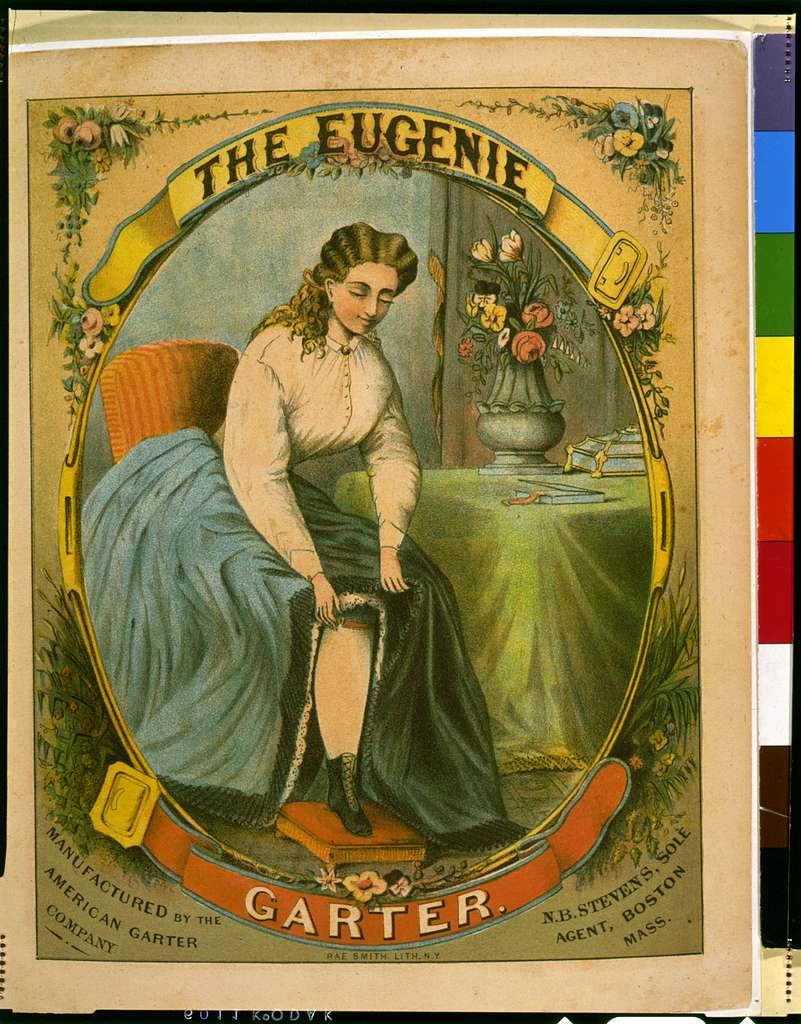

The rise of the commercial possibility of Valentine’s Day

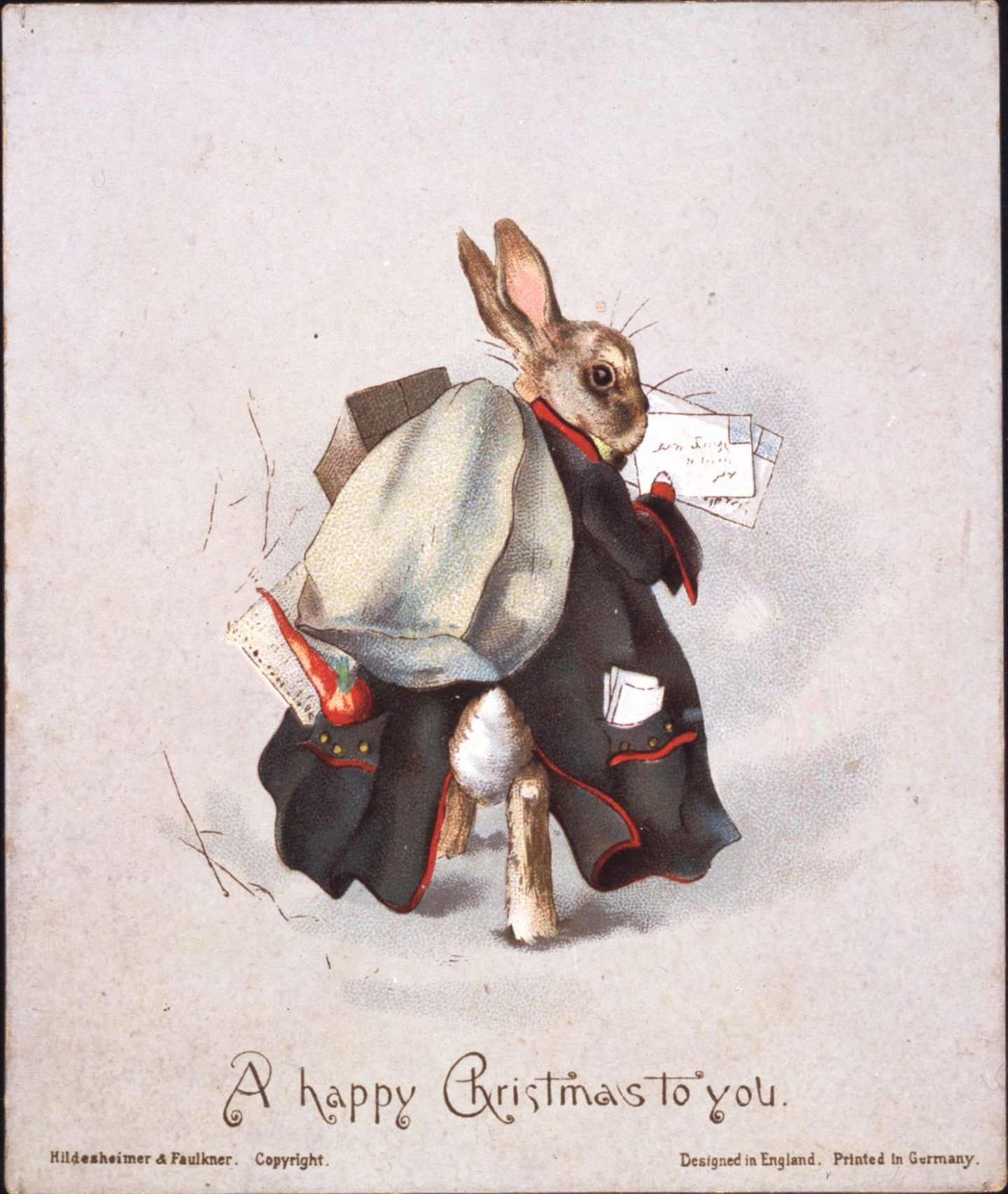

While Valentine’s Day had long since been celebrated in Britain, the industrial age brought the rise in the production of cards in factories, while previously they had been handmade. The invention of the “penny post” created lovely expressions of love that could be sent in the mail or left at the home of the individual you were courting or hoped to court. They ranged widely in quality and therefore cost, with more elaborate options being seen as proof of a lover’s true level of feeling.

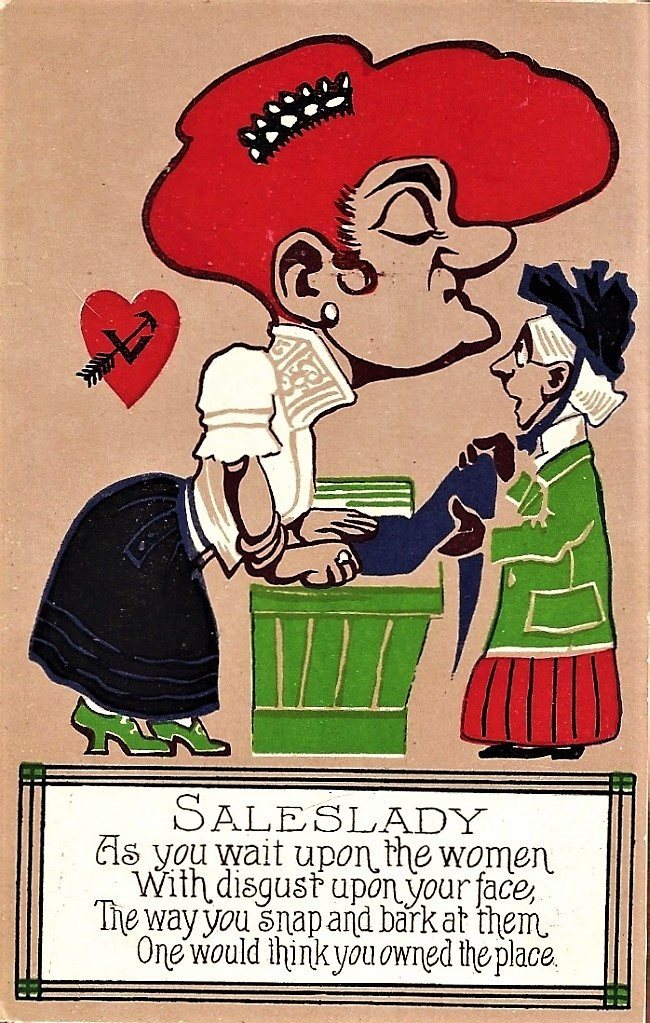

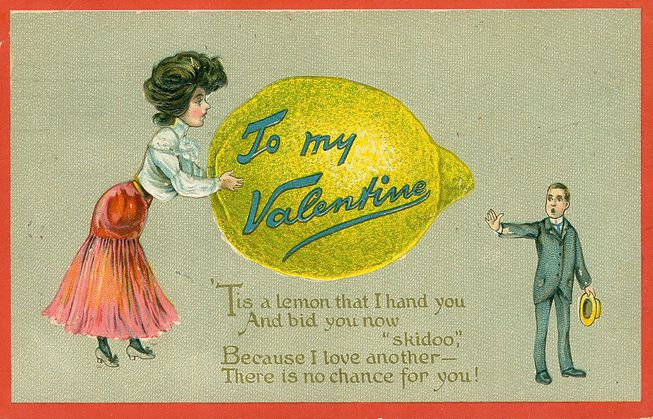

While I have always enjoyed Victorian Valentine’s, I was unfamiliar with so-called “vinegar Valentine’s” produced during this time. Such cards were the “anti-Valentine’s” card, meant to be sent to someone you didn’t care for. This could be someone who had refused you, or, as I discovered in some follow-up research to the episode, it could simply be an acquaintance you didn’t care for. The example below appears to be meant for an irritating shop lady, the next one to a refused lover. I am glad we no longer use Valentine’s Day as an excuse to be nasty!

The most well-known producer of the penny post was Johnathan King, who owned a factory next to his stationery shop. One year he sent the “ultimate” Valentine’s Day card to a woman he was courting, which included page after page of delicate expressions of love. Tucked into the back panel of the “card” was a marriage proposal. The couple did marry and proceeded to have 15 children together, one they named Valentine.

The corset’s “tie-in” with Spiritualism

Having just written a post about the dress reform movement, I was tickled pink to learn about the connection between corsets and the Spiritualist practices that gained so much popularity in the 19th century. As you may know, the movement began in America around the middle of the century and quickly spread to England. This migration mixed well with the ever-growing “cult of mourning” taking hold in the U.K., as it provided a means of connecting with those in the next realm. One of the primary Spiritualist rituals was the seance, in which small groups would gather and communicate with the dead through the mystical gifts of a “medium.” Young women were most commonly seen as bearing the gifts of mediumship and were thought to sometimes embody the souls of the dearly departed during such rituals.

After conducting a brief prayer with the group, in some seances the medium would leave the room, returning shortly after under the influence of an unknown being. The personage would give messages from beyond to certain group participants, touch some participants, and bond with them in various ways. In some cases, the participants would be allowed to touch the body of the spirit, and this was how some were converted to believers, as the figures were not wearing corsets. Remarkably, the use and the expectation of women to wear corsets were so engrained in British society at the time that it was believed that only a woman from another realm would appear before a group without one.

The case of Isabella Robinson

As the century progressed, so did the desire that women had for autonomy, opportunity, and their own versions of happiness. As A Very British Romance points out, however, some areas of society were slow to catch up, and many women suffered unfortunate fallout from some of their choices. One such woman was Isabella Robinson. In 1854 she was trapped in a marriage to a distant, unkind man and leading a most unsatisfying existence. We know this because she left behind detailed diaries in which she lamented her situation. She also outlined her friendship with a friend and doctor she enjoyed time with and whom she eventually had a romantic and passionate affair with. Several segments of the diary are read on this episode and I couldn’t help but cheer Isabella on as I heard her descriptions of her encounters with her lover.

Unfortunately for Isabella, the diaries were discovered by her husband, who wasted no time suing her for divorce in one of the country’s very first such cases. The diaries were not only used as evidence in the case against her, excerpts ran in newspapers around the country. The contents were far more explicit than anything in publication at the time and caused an enormous stir. They were also full of innuendo and flowery language so indicative of the time. In one passage Isabella wrote of the joy the “effects of his presence” gave her, in a passage somewhat obviously referring to a sexual encounter.

It was also this coy relating of events that saved Isabella in the end, as the court determined, after months of deliberation, that the evidence that she had actually committed the act of adultery was too weak.

Are you tuning into A Very British Romance? If so, what has been your favorite part so far? Next week the show will cover the changing tides of society and romance in the aftermath of World War One and Two.

Thank you for sharing these stories,I have found them enjoyable and very interesting.Can’ wait too read more of your stories.