Author: Christine Skirbunt

250 Years

25 Decades

One Nation in Motion

The United States of America is turning 250 in 2026 and for two and a half centuries it has stood as both a symbol of self-determination and as an experiment in government, inspiring many other nations in their own pursuits of democracy. But how do we begin to fully honor 250 years of American history in a single article? The story of the founding of America to the present day is far too expansive for one anecdote, and to try to make it so would be a disservice to the country and its people.

But when we break the stories down, decade by decade, something remarkable happens: patterns emerge from the commotion, voices rise from the margins, and history becomes more tangible…more human.

So instead of attempting to summarize one major event to speak for all of America’s last 250 years, this article takes a different approach: one defining moment for every decade since 1776. Some are sharp turning points; others are quieter shifts that shaped who we’ve become. Not every story may be what one would expect to be included – but within each story is a deeper thread. Often, it’s the so-called “small” moments that make the big ones possible.

Each decade also features a Factoid – a lesser-known detail from the same era that adds surprise, depth, or reflection. Some are joyful, some tender, many complex, but all of them matter.

It’s important to remember this isn’t a timeline. It’s a collection of living snapshots of a country still in progress. And while the last 250 years have brought extraordinary change, one thing remains true: the American story is not finished.

Keep an eye out for the “tie-ins” woven throughout! These highlight where fashion, domestic life, and untold women’s histories intersect. Moments where overlooked voices that helped stitch the fabric of a nation together finally get their say.

Decade 1: 1776–1785

The Declaration of Independence launched a long and brutal fight for freedom.

On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, but the fight for liberty had already been underway. The Revolutionary War had started more than a year earlier, on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. From that point on, Americans endured over eight years of war – not winning full independence until the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. One of the first public readings of the Declaration of Independence happened on July 8, 1776, in Philadelphia. And George Washington had it read aloud to his troops in New York to raise morale. The country’s founding wasn’t just declared – it was hard-won.

Factoid: Fireworks lit up the sky as early as 1777.

Philadelphia marked the first Independence Day on July 4, 1777, with bonfires, cannon salutes, and fireworks. Fireworks originated in China over a thousand years ago and were brought to Europe through trade. By the 18th century, they were widely used in European celebrations, especially royal and military events. American colonists adopted the tradition from Britain. So, when Philadelphia celebrated Independence Day on July 4, 1777, fireworks were a natural choice for marking such a momentous occasion.

The Pennsylvania Evening Post reported on July 5, 1777, that “the evening was closed with the ringing of bells and a grand exhibition of fireworks, which began and concluded with thirteen rockets.” The thirteen rockets were, of course, symbolic of the thirteen colonies.

Decade 2: 1786–1795

The Constitution was written – and almost didn’t pass.

In 1787, delegates from twelve of the thirteen states gathered in Philadelphia to fix the weak Articles of Confederation. What emerged instead was the U.S. Constitution, drafted behind closed doors in a sweltering summer hall. The debates were fierce – how strong should the federal government be? How would states be represented? And what about slavery? After months of negotiation, the final document was signed on September 17, 1787, but it still had to be ratified by the states. The Constitution wouldn’t take full effect until March 1789! Even then, it took the promise of a Bill of Rights, added in 1791, to win over the skeptics. The government we know today almost didn’t happen.

Factoid: The first American fashion trend? Presidential hair envy.

George Washington’s iconic hairdo wasn’t a wig – it was his real hair, powdered and styled. But wigs were still trendy, and by the 1790s, American elites had begun copying his look as a symbol of “virtuous” republican leadership. Fashion and politics were already intertwined.

Decade 3: 1796–1805

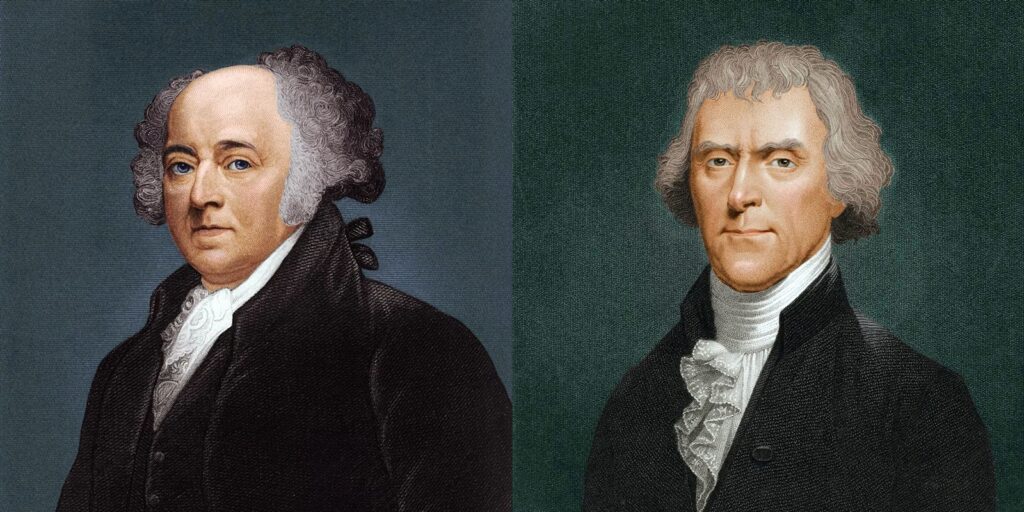

America proved it could transfer power peacefully.

In 1800, Thomas Jefferson defeated incumbent John Adams in one of the nastiest presidential elections in history – complete with mudslinging, fake news, and accusations of tyranny and atheism. But what mattered most was what happened next: a peaceful transfer of power between rival political parties. It was the first time in modern history that a nation changed leadership by ballot, not bloodshed. Jefferson called it “the Revolution of 1800,” and it proved that the Constitution – and democracy – could actually work.

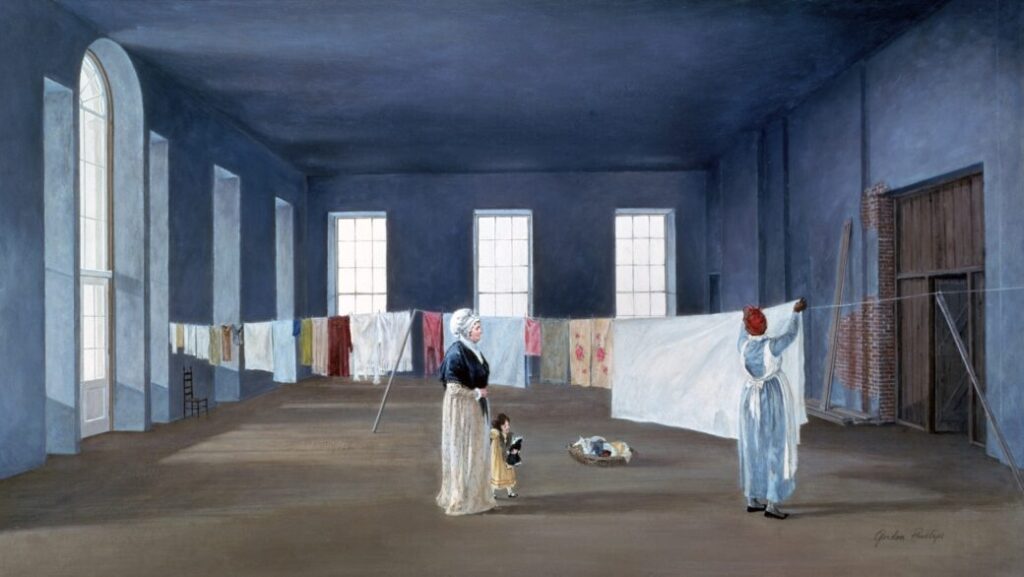

Factoid: The White House got its first residents – but not furniture.

President John Adams and his wife, Abigail, moved into the still-unfinished Executive Mansion in 1800, becoming its first residents. Abigail famously hung wet laundry in the East Room because it was the only dry space available.

Decade 4: 1806–1815

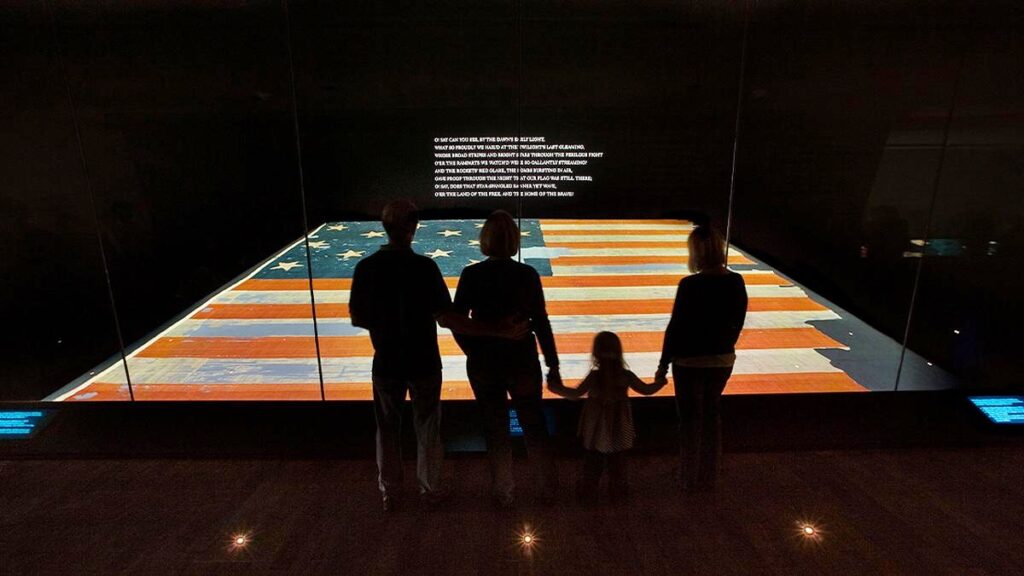

The War of 1812 gave us the national anthem – and a renewed sense of identity.

Fought between the U.S. and Britain from 1812 to 1815, the War of 1812 was messy, controversial, and nearly ended in disaster. The British burned the Capitol and White House in 1814. But Americans rallied, especially during the Battle of Baltimore, when Fort McHenry withstood a 25-hour bombardment. Watching from a British ship, lawyer Francis Scott Key was so moved to see the American flag still flying “by the dawn’s early light” that he authored a poem – “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It later became the national anthem and a lasting symbol of American endurance.

Tie-in: The actual flag that flew over Fort McHenry was sewn by Mary Pickersgill, a professional flag maker in Baltimore. It measured 30 by 42 feet and required a team of women, including her daughter and nieces, to complete it.

Factoid: The White House got a rebuild – and a name.

After being burned by the British, the Executive Mansion was rebuilt and painted white to hide scorch marks left by the British. It wasn’t officially called the White House until the early 1900s, but the nickname started circulating right after the war.

Decade 5: 1816–1825

The “Era of Good Feelings” brought unity – and big dreams of expansion.

After the War of 1812, the country entered a period of political calm known as the Era of Good Feelings (1817–1825), named for the widespread national pride and sense of unity under President James Monroe. With only one major political party left standing (the Democratic-Republicans), partisan bickering quieted – at least temporarily. Monroe toured the country to promote national harmony and wore American-made clothes to encourage independence from European goods. It was a brief but hopeful moment when Americans believed the future was theirs to build.

Tie-in: American fashion began subtly shifting during this era. High-waisted “Empire” dresses gave way to more structured silhouettes, and there was a growing emphasis on distinctly American-made textiles and clothing as a matter of patriotic pride.

Factoid: The Erie Canal opened a watery highway to the West.

Begun in 1817 and completed in 1825, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes – allowing goods and people to move faster and cheaper. It turned New York City into a major trade hub and kicked off a migration boom to the Midwest.

Image Sources:

- Declaration of Independence Signed: https://www.history.com/articles/declaration-of-independence

- The First Fourth of July Celebration: ChatGPT

- George Washington Lansdowne Portrait by Gilbert Stuart: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lansdowne_portrait

- Abigail Adams Drying Laundry in East Room by Gordon Phillips: https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/abigail-adams-used-the-east-room-to-dry-the-laundry

- Sewing The Fort McHenry Flag: ChatGPT

- The Original Star-Spangled Banner Flag: https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/star-spangled-banner4

Leave A Comment