How are you celebrating the arrival of spring? Today, many of us in North America take to our local parks and trails to do so, but in times gone past communities marked the occasion with rituals such as dancing around the maypole.

Most of us haven’t participated in the tradition yet still think of spring magic when we see images of it. That’s because it is a depiction that goes back many hundreds of years. Shall we bring it back?

Origins – scandalous or sacred?

Many people will say that the maypole was originally a pagan fertility symbol. Well…maybe. The truth is that the origin hasn’t been officially traced. That being said, it would, over time, come to be thought of as such. It would even be outlawed completely by an Act of Parliament under Oliver Cromwell.

Charles II would permit the tradition to be restored and the activity would remain a mainstay in English springtime celebrations for hundreds of years, even continuing in school fetes today. However, the maypole would forever be linked with fertility rituals, with detractors at every step of the way.

Take, for instance, the story of one plucky pilgrim, Thomas Morton.

Thomas Morton: maypole disruptor

Thomas Morton was indeed a pilgrim, but as The Public Domain Review points out, he was a different kind of pilgrim. Although he arrived to the colonies just two years after the Mayflower landed, his ideas about the possibilities of the new land were entirely different from the Puritans. He saw potential for farming, business, and well, some fun. In 1627 he sent his local community into a collective rage when he sought to erect a maypole as part of a general celebration for spring and their successes thus far.

Morton took the party planning quite seriously and his maypole sounds impressive. In his own words those involved:

“devise amongst themselves to have it performed in a solemn manner with revels and merriment after the old English custom, prepared to set up a May-pole upon the festival day of Philip and Jacob; and therefore brewed a barrel of excellent beer, and provided a case of bottles to be spent, with other good cheer, for all comers of that day. And because they would have it in a complete form, they had prepared a song fitting to the time and present occasion. And upon May-day they brought the May-pole to the place appointed, with drums, guns, pistols, and other fitting instruments, for that purpose; and there erected it with the help of savages, that came thither of purpose to see the manner of our revels. A goodly pine tree of eighty feet long, was reared up, with a pair of buck’s horns nailed on, somewhat near unto the top of it: where it stood as a fair sea-mark for directions how to find out the way to mine host of Ma-re Mount.”

While he may have gotten many locals to join in the celebrations, those in charge of the settlement operation weren’t as amiable. The party was shut down and the maypole was destroyed. Some accounts state that Morton was arrested and sent back to England near starvation while others state that he left, frustrated with the Puritan leadership.

So, were the outraged Puritans justified? Not so fast, say some historians…

The Wikipedia entry on the topic references the book The stations of the sun : a history of the ritual year in Britain by Ronald Hutton. The extensive history cites multiple scholars, including Hutton, that argue the maypole was originally created as a way to celebrate nature and the coming of spring and little more. Reads the Wikipedia entry:

“English historian Ronald Hutton concurs with Swedish scholar Carl Wilhelm von Sydow who stated that maypoles were erected “simply” as “signs that the happy season of warmth and comfort had returned.” Their shape allowed for garlands to be hung from them and were first seen, at least in the British Isles, between AD 1350 and 1400 within the context of medieval Christian European culture…

The anthropologist Mircea Eliade theorizes that the maypoles were simply a part of the general rejoicing at the return of summer, and the growth of new vegetation. In this way, they bore similarities with the May Day garlands which were also a common festival practice in Britain and Ireland.”

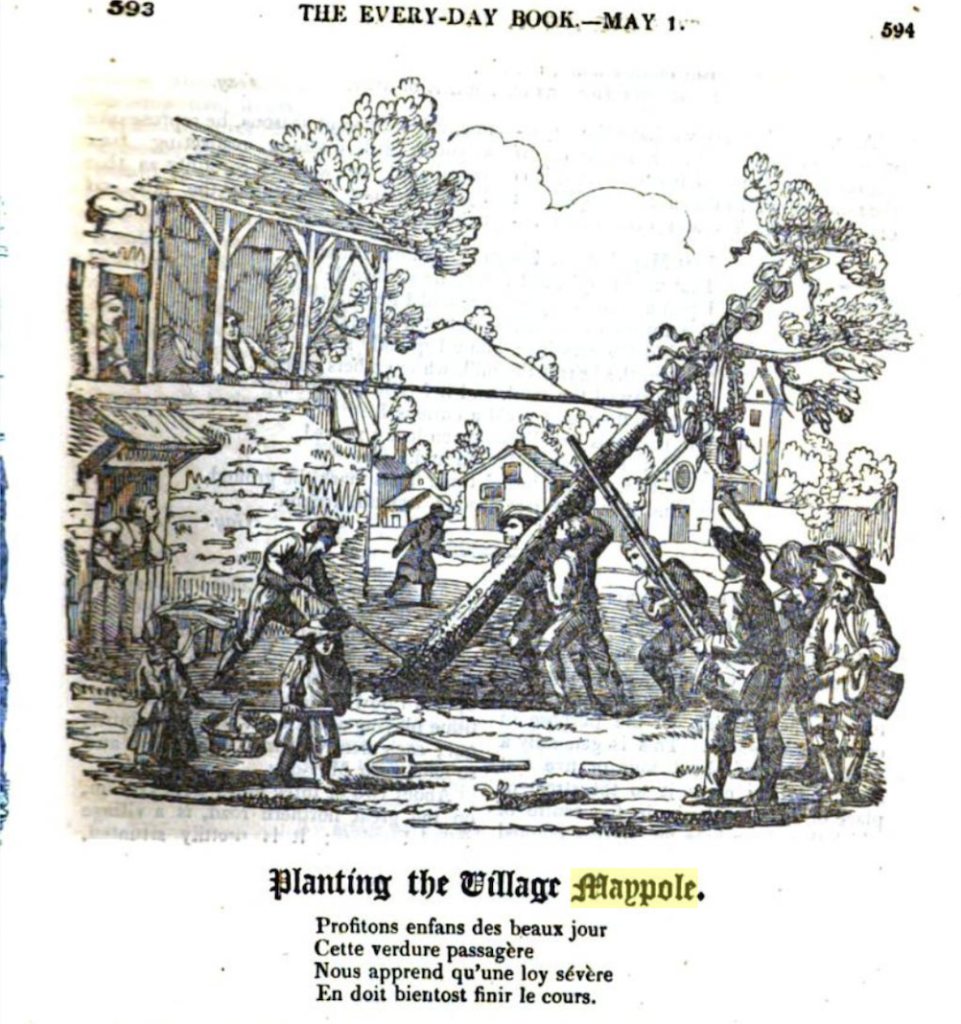

It is also worth noting that early maypoles did not include the ribbons and garlands used in more modern times for dancing, but were rather a large decorated pole as seen below.

Want to see a maypole dance? Check out this darling video I found from 2012:

English revival

Whatever people think of the symbolism and origin of the maypole, it has remained a spring staple in Europe for centuries. I lived in Germany about ten years ago and it was common to see villages with maypoles up during the spring months, both in parks and as decoration in the middle of town as seen below.

You could also say that May Day had its “heyday” in Europe in the mid to late 1800s, with maypole imagery abounding. I have read that this was partially due to a revival in enthusiasm for English customs taking place. The Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, published in 1830 provides a history of things that had happened on each day of the year up to that time, and numerous suggestions on how to celebrate various holidays. The entry for May 1st, May Day, has over 20 references to maypoles, including a story about a French town that made a tradition of erecting a maypole as part of their annual celebrations.

The book also includes the poem “The Country Maypole”:

It is a pleasant sight, to see

A little village company

Drawn out upon the first of May

To have their annual holiday –

The pole hung round with garlands gay;

The young ones footing it away;

The aged cheering their old souls

With recollections and their bowls;

Or, on the mirth and dancing failing,

Their oft-times-told old tales re-taleing.

Maypoles for the masses

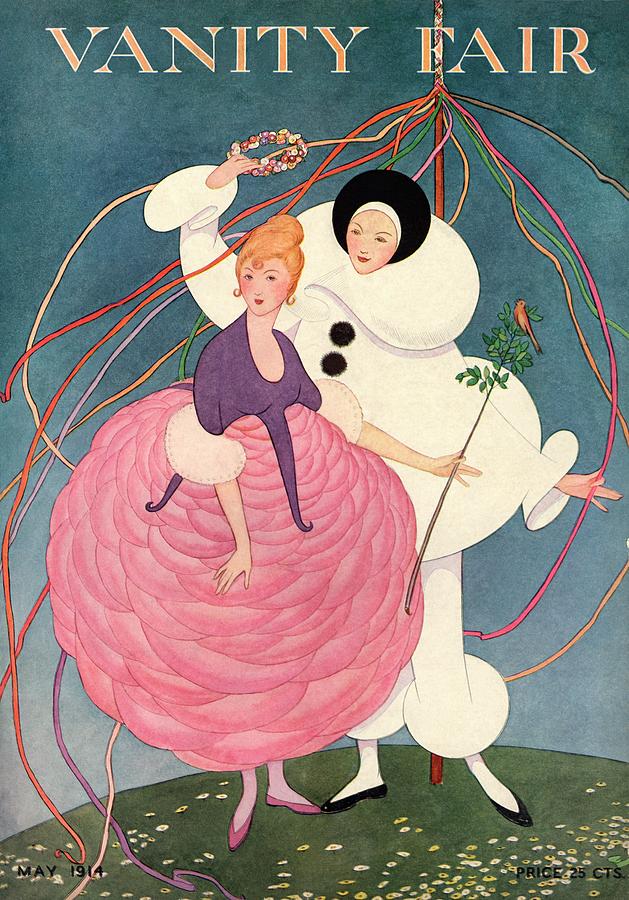

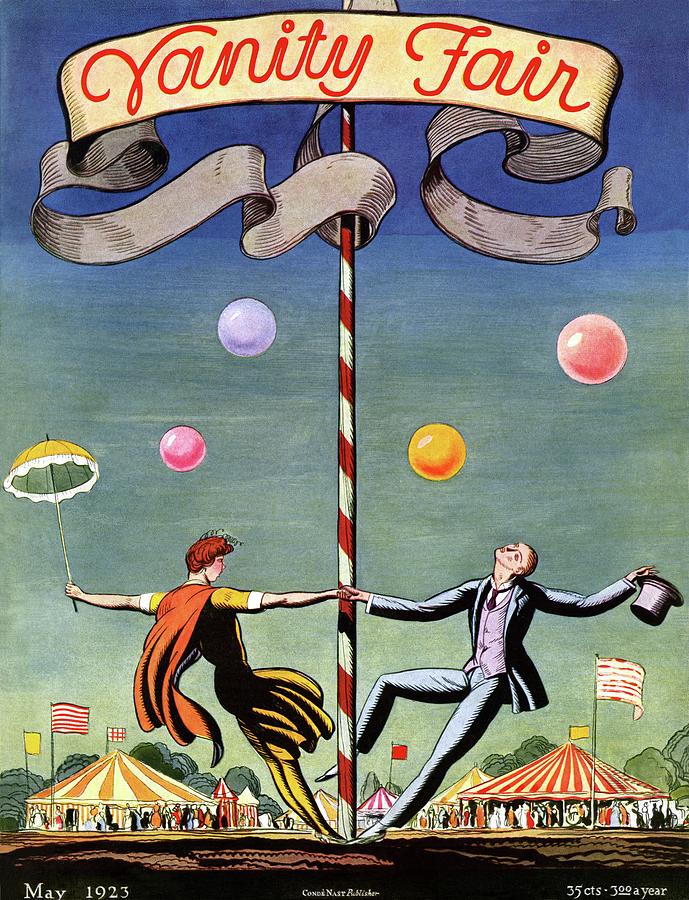

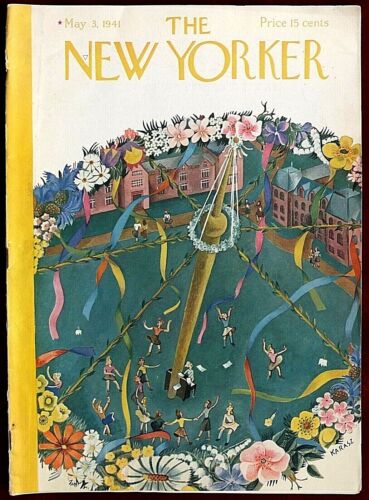

The popularity of maypoles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is also seen in the mass media of the time.

Two covers of Vanity Fair featured the tradition, one in 1914

And one in 1923

Multiple covers of The New Yorker have featured maypoles, my favorite from 1942.

The 1930s and 40s appear to have been a popular time in America for the tradition, as I came across many photographs of communities participating in it.

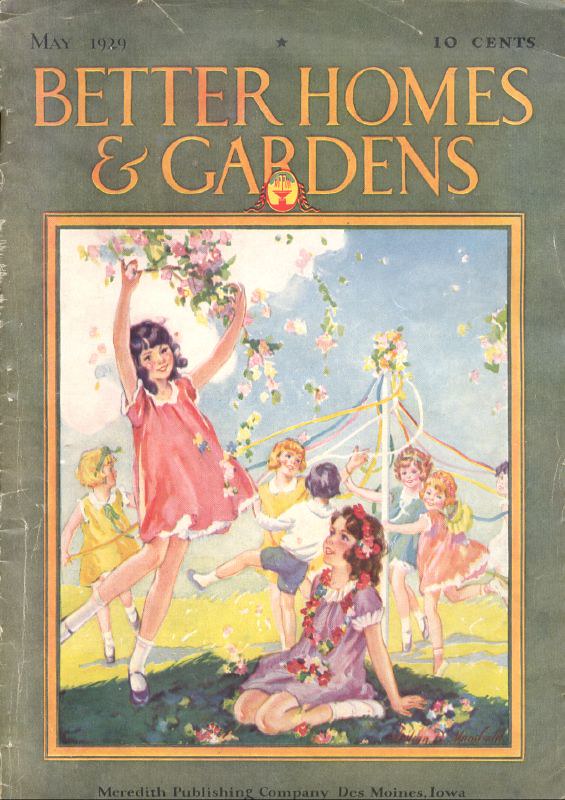

This charming 1939 cover of Better Homes and Gardens confirms that maypoles were trending during this time.

Have you danced a maypole? Let us know in the comments!

You may also enjoy these history posts:

Rosy cheeks: the Victorian way

Have fun, but not too much fun: Victorian ball etiquette

Yes I have danced the Maypole grew up in South Africa and always on May 1 there was a Maypole. As a child I thought it a lot

of fun. South Africa been in the Southern Hemisphere we weren’t celebrating Spring.