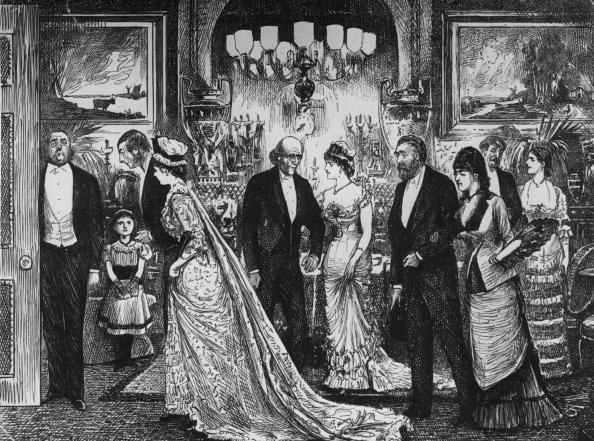

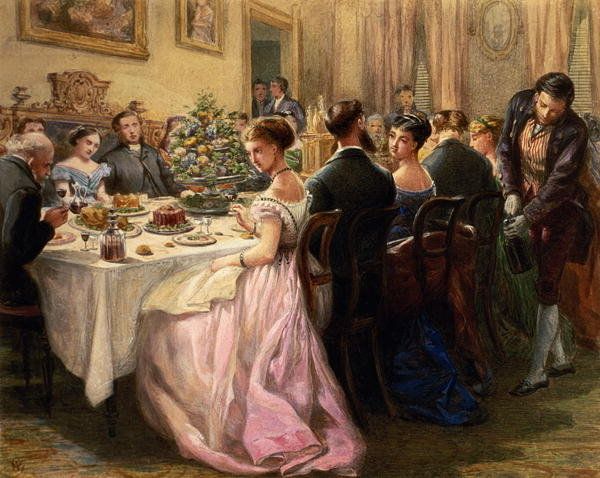

It might just be me, but I absolutely love Downton Abby scenes where dining etiquette is discussed. From the downstairs staff being trained to how things played out upstairs, I find the details so intriguing; especially considering how much things have changed since. Victorian table etiquette carried over into the first decades of the 20th century and then in so many regards was lost to history. This is one area of life that I think we would have been well-served to maintain, as it is often quite horrifying to me to see how lacking some are when it comes to table manners.

So, exactly how far have we strayed? Let’s take a look at the standard Victorian table etiquette.

Victorian table etiquette according to the experts

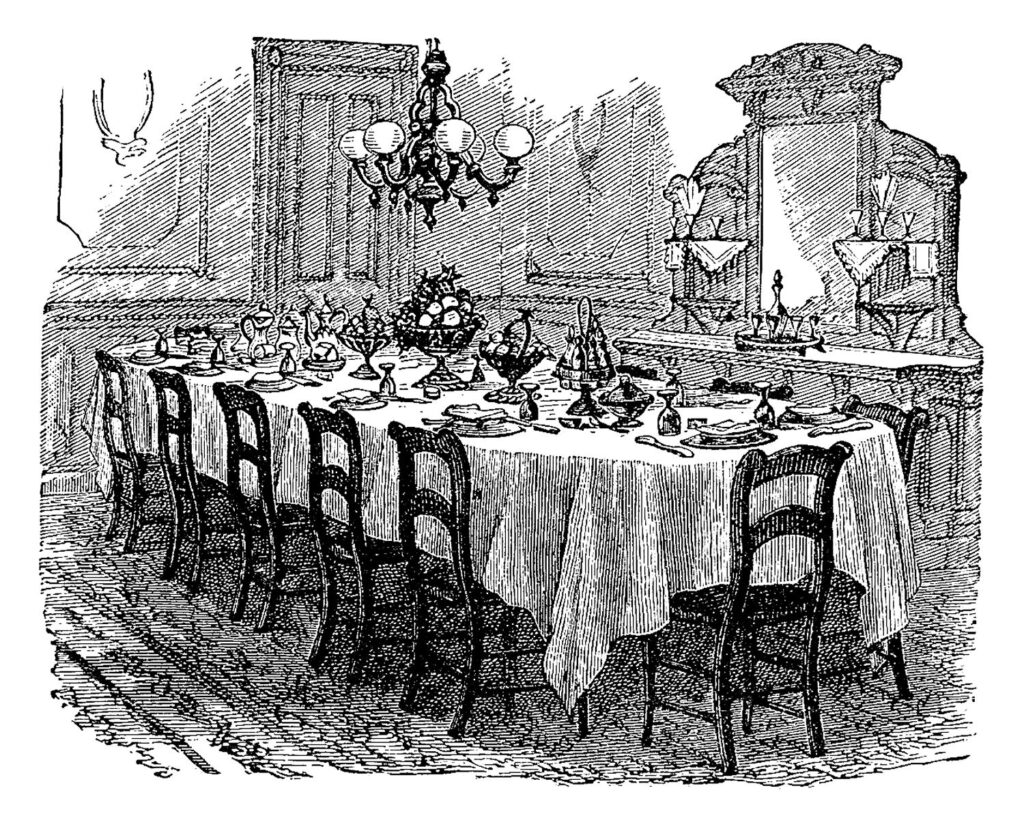

I had originally planned to give a general overview of the top most important things to know when attending a Victorian dinner party. I then started combing through etiquette manual after etiquette manual and quickly saw a few surprising common threads stand out to me. A huge emphasis on correct ways of doing certain things that I wasn’t quite expecting. Some are downright laughable and I thought I’d share them.

Off-limits conversation topic: the food itself

The first thing that I noticed that I hadn’t predicted is that in Victorian times it was considered wildly inappropriate on both the part of the hostess and the guests to focus on the food. Instead, it was meant to be accepted without much conversation or examination. This is a far cry from today’s dinner table when the food itself is often the very thing people talk about the entire time.

Here’s what the experts had to say on the topic:

Beadles Dime Book of Practical Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen, 1859:

“A mistress of a house ought never to appear to pride herself regarding what is on her table, now confuse herself with apologies for the bad cheer which she offers you; it is much better fr her to observe silence in this respect and to leave it to her guests to pronounce eulogiums on the dinner; neither is it in good taste to urge guests to eat nor to load their plate against their inclination.”

Woman in Her Various Relations, 1851:

“Do not press people to take more than they seem inclined to eat. This absurd custom is entirely abandoned.”

The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility, 1856:

“Do not press people to eat more than they appear to like; nor insist upon their tasting of any particular dish; you may recommend one as to mention that it is considered excellent.”

The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness, 1876:

“Never examine minutely the food before you. You insult your hostess by such a proceeding, as it looks as if you feared to find something upon the plate that should not be there.”

But if you find something crawling around on your plate?

“If you find a worm on opening a nut, or in any of the fruit, hand your plate quietly, and without remark, to the waiter, and request him to bring you a clean one. Do not let others perceive the movement, or the cause of it, if you can avoid doing so.”

Besides these entries, every book makes mention of taking food without asking about it, refraining from talking about the food as you eat it, and not remarking about whether you enjoyed a particular dish or not.

Separate spouses and colleagues

While I have noticed that the hostess and hostess sit at separate ends of the table when watching Victorian period pieces, I don’t think I realized that it was a standard pratice to ensure that no spouses were seated next to each other. It was of great concern to a hostess to provide an environment for easy, light, communal conversation. It was believed that when seated next to each other a husband and wife would carry on their own conversation, getting in the way of this goal. The same effort was meant to be taken to separate people of similar professions, as they would find too much common ground.

Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society, 1890:

“If the number of gentlemen is nearly equal to that of the ladies, we should take care to intermingle them; we should separate husbands from their wives, and remove near relations from one another as possible; because being always together, they ought not to converse among themselves at a general party.”

The lady’s guide to perfect gentility, 1856:

“We should, as much as possible, avoid putting next one another two persons of the same profession, as it would necessarily result in an aside conversation, which would injure the general conversation, and consequently the gaiety of the occasion.”

“We should separate husbands from the wives, and emove near relations as far from one another as possible, because, being always together they ought not to converse among themselves in a general party.”

Keep your hands to yourself!

I have always considered putting your elbows on the table to be bad manners and try to avoid this in any dinner that is not super casual. I knew that this was a custom that came down from Victorian times, but I didn’t realize just how against having hands on the table they were. All of the five or six books that I consulted for this post made a strong mention of it.

Woman in Her Various Relations, 1851:

“When not engaged in eating, let not your fingers find employment in making pellets of bread, or in playing with the table furniture.”

Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society, 1890:

“Never lay your hand or play with your fingers upon the table. Neither toy with your knife, fork, or spoon, make pills of your bread nor draw imaginary lines upon the table cloth.”

The matter of correctly engaging with one’s bread was another hot topic and the one we will discuss next.

Bread: not up for debate

How to properly enjoy bread was a matter not up for debate in Victorian table etiquette. From what I can tell, two things were expected: That a piece of bread never be cut before having a bite, and that each bit was torn from the slice or roll before being put into one’s mouth. And as far as enjoying with various foods? Proceed with caution.

Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society, 1890:

“It is considered vulgar to dip a piece of bread into the preserves or gravy upon your plate and then bite it. If you desire to eat them together, it is much better to break the break to small pieces, and convey these to your mouth with your fork. “

“Some persons use their bread at dinner to dry up their plates; this is intolerable beyond the family circle, and even there is rather childish.”

The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness, 1876:

“Do not break bread into your soup. Break off small pieces and put into your mouth, if you with, but neither bite it from the roll nor break it up, and eat it from your soup-plate with a spoon.

In eating bread with meat, never dip it into the gravy on your plate, and then bite off a small piece, put it upon your plate, and then, with a fork, convey it to your mouth.”

Wine: up for a lot of debate

The one area that lacked consistency in the etiquette manuals was that of serving and partaking in wine. Serving wine at any dinner party is a custom that I am in full favor of, what about you?

A Word to Women, 1898:

A dinner party without wine is rather a mournful business. I was at one once. It was several years ago but I have never forgotten it. It was the first occasion on which I ever tasted a frightful temperance drink called “gooseberry champagne.” It is also likely to be the last! Oh no! Do not let us have tasteless dinner parties!”

Beadles Dime Book of Practical Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen, 1859:

“In drinking wine you should say to your neighbor, “Sir, may I offer you?” and not employ the ungenteel phrase, “will you take?” as if you were at the bar of some ordinary drinking-saloon.”

Woman in Her Various Relations, 1851:

“Wine drinking is no longer considered a part of a dinner ceremony. It is not practiced at the most refined tables, and the best part of community discard it wholly.”

The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness, 1876:

“No lady should drink wine at dinner. Even if her head is strong enough to bear it, she will find her cheeks, soon after the indulgence flushed, hot, and uncomfortable; and if the room is warm, and the dinner a long one, she will probably pay the penalty of her folly, by having a headache all evening.”

Last but not least: what to do what one’s napkin

Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society, 1890:

“Never use a napkin in the place of a handkerchief by wiping the forehead or blowing the nose with it.”

Woman in Her Various Relations, 1851:

“Spread your napkin in the lap, the ladies take off their gloves and lay them under the napkin.”

“When all through, the guests fold their napkins, and lay them on the table. The lady of th house rises to the drawing-room. If the lady of the house lays her napkin on the table after the meats are through, the company will do the same. Colored Napkins are often used, and are best for fruit.”

“If finger-glasses are served round to each person at the end of the second course, it is that you may dip your fingers in, and wipe them on your napkin. Observe after this, whether the lady of the house throws her napkin on the table or retains it, and do likewise, as the customs of the houses vary…If colored napkins of dailies are served, use them to wipe your fingers on, after eating fruits, to avoid stains.”

The lady’s guide to perfect gentility, 1856:

“It is ridiculous to make a display of your napkin; to attach it with pins to your bosom, or to pass it through your button-hole.”

What do you think about Victorian table etiquette? What would you love to still be in place today and what are you glad to not worry about anymore?

More on Victorian culture:

Victorian letter writing rules

I, too, would like to see many of these etiquette rules back in use again. Most people eat like pigs. (I often times eat too quickly and this would help me learn to slow down.)

I couldn’t agree more! I was also taught proper table manners growing up and am glad for it!

I thought it was rather interesting and I remember being told not to put my elbows on the table and to put my napkin in my lap. Some of the other stuff was funny.

Great information. It is a shame that Victorian table manners are out of vogue. Most people eat like pigs and I loathe sitting across from them during a meal. I was instructed on proper table manners by my father during the 1950’s and he was a stickler for proper use of utensils.