I love the fresh start of a new year! I think that even if it is just symbolic, the rare opportunities that we have in life to start a new chapter can be great chances to reevaluate our lives and make changes that ensure we are making the most of our time on this planet. I do this by thinking about all the things I want in my life and then creating something permanent to remind me of these intentions all year long. Last year I created a beautiful word art collage for 2021 that I hung in my room to remind me of my goals each morning. And it worked! I had a great year full of all the things I wished for in one way or another. I like to think of this practice as my own form of New Year’s resolutions, but more effective.

New Year’s resolutions have gotten a bad wrap in the past several years and seem to be getting less trendy as time goes by. I have been curious about how people in the Victorian and Edwardian eras recognized the beginning of a new year as a new lease on life and if they were any more effective at sticking to their New Year’s resolutions. As it turns out, plenty of individuals in the 19th and early 20th centuries had vices that they were keen to get rid of in January. And there was just as much skepticism about the effectiveness of New Year’s resolutions.

If you decide to forego beginning of the year goals or out your own spin on things like I do, hopefully, you’ll rest easy knowing that people have been struggling with New Year’s resolutions for a century or more.

Here today, gone tomorrow

People have been wary of New Year’s resolutions since the Victorian era, though that hasn’t prevented people from making them.

This trend is nothing new as a 1913 Exeter and Plymouth Gazette sarcastically points out:

“Did you make any New Year resolutions? Of course you did. Who doesn’t? There is something irresistibly magnetic about the first day of a New Year–something that compels a new channel of thought. One becomes not only retrospective but introspective. One looks back with regret for the things that might have been done, and deplores others which have been done, and forthwith makes a resolution to remedy the omissions this year. This is but natural. There is something wondrously consoling in being able to say that one hasn’t once permitted that little vice to creep into life this year. But the mischief is that this fascination doesn’t as a rule last longer than the first twenty-four hours. It is so much easier to make resolutions than to keep them. Frail is human nature!”

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette on January 4, 1913.

Despite the lack of follow-through and abundance of statistics on the number of resolutions that fail early in the year (more on that to come), personal development enthusiasts continue to believe in the power of New Year’s resolutions, myself included. A recent BBC blog post points out that there is a lot of validity in setting goals to begin the new year including the fresh-start effect and the likelihood of achieving a goal and the benefits of personal success. There is also the simple benefit of reflecting on one’s life, noted as early as 1830 in The Book of Days:

“Every first of January that we arrive at, is an imaginary mile-stone on the turnpike of human life; at once a resting place for thought and meditation, and a starting point for fresh exertion in the performance of our journey. The man who does not at least propose to himself to be better this year than he was last, must be either very good, or very bad indeed! And only to propose to be better, is something; if nothing else, it is an acknowledgment of our need to be so, which is the first step towards amendment. But, in fact, to propose oneself to do well, is in some sort to do well; positively; for there is no such thing as a stationary point in human endeavours; he who is not worse to-day than he was yesterday, is better; and he who is not better, is worse.”

Write it down

A recent New York Times article states that a third of resolutions fail before the end of January. The reasons? Goals are often based on the opinion of someone else, too vague, or lacking a clear plan on how to achieve them. As I mentioned earlier, my secret to success this year was looking at my intentions each day. This is a tactic outlined in another New York Times piece, this time from 1893. The article tells the story of two men who happen upon a sign in a business window reading “resolutions engrossed.” With that, one of the men gets a clever idea:

“I have a theory–came to me this very minute–that the reason I’ve not kept the resolution I’ve adopted every New Year’s since I left college is that I’ve forgotten each year just what the resolution has been. Now I propose to put the thing into good, legible writing and hang it up in my bedroom and then, by Jove, I’ll have it by me all the time. It’ll be a sort of conscience to me. ‘Now mind you, Jim,’ it’ll say to me every morning when I get up, ‘only three cocktails to-day, and they must be separated too, mind that, Jim.”

As it turns out, the confused storekeeper has to tell them that the types of resolutions engrossed are of the political type, not New Year’s, but the men have given him a new product idea.

Want to learn more about Victorian New Year’s traditions? Check out our blog post: Victorian New Year’s Blessings: Pigs and Clovers

Swearing off vices

The vice of over-drinking noted in the New York Times piece was apparently a big concern in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, as I found many references to “swearing off” drunkenness (though few references to giving up alcohol completely).

A limerick submitted to the New York Times in 1910 read:

I trust it will not appear too liberal to my fellow-townsman–the great trouble with New Year resolutions is, they are apt to be made too radical. I am speaking from experience.

My effort, for which there will be no charge, would make the “limerick” read as follows:

Good New Year resolves are in style.

The bulk of them force us to smile.

Were I making one now

I should certainly vow

I’ll only drink once in a while.

-X “Sun Ray” Specialist.

Englewood, NJ Dec. 27, 1910

Of even more concern than over drinking was smoking. When it comes to this vice I found both references to “swearing it off” but just as many pointing to the fact that few men kept the resolution very long. The Wheeling Daily Register, for instance, spoke with the owner of a local tobacco shop shortly after the beginning of 1869:

“New Year’s Resolutions–A striking illustration of the truth of the proverb that a certain road is paved with good intentions was the remark made by a tobacconist the other day. “On New Year’s Day, said he, “I always find a sudden and tremendous falling off of my business. After doing an unusual amount of business Christmas week, I sell scarcely any tobacco on New Year’s Day, and indeed very little during the first week thereafter. Gradually, however, my old customers, having broken their New Year’s resolutions, come dropping in one by one, and before the end of January I sell as many cigars and as much tobacco as ever–indeed rather more.” Poor human nature!”

–The Wheeling Daily Register, January 4, 1869

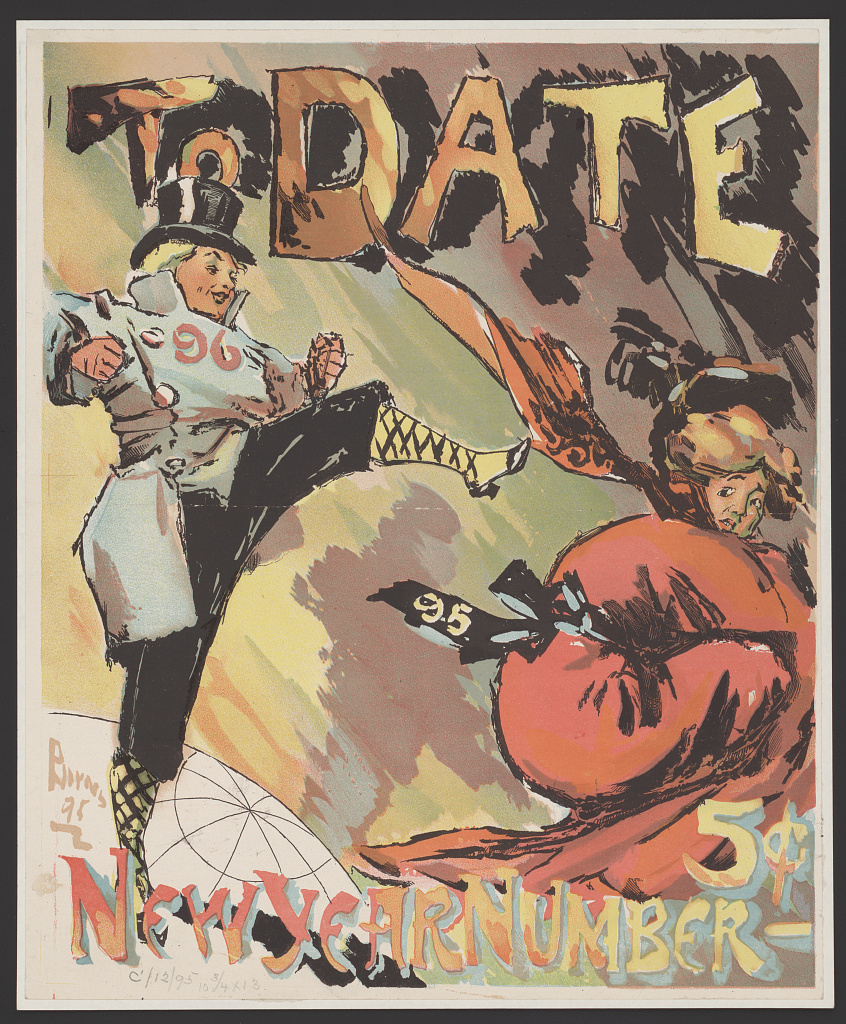

To Date magazine, 1895

Resolve to be courteous

While Victorian and Edwardian men took it upon themselves to swear off tobacco and drunkenness, there were also those in society that sought to encourage those around them to resolve to be more courteous. In a 1914 letter to the editor a Mr. Brennan said that men should recommit to gentlemanly behavior in the new year:

“In new of the approaching season for New Year’s resolutions let all the male citizens of this city remember that there is one everyday courtesy to women that is deeply appreciated by them and which every man has frequent opportunities to put into effect: that of always vacating his seat in Subway, surface, or elevated trains in favor of any woman he sees standing. If this were put into effect through New Year’s resolutions, what a deep and lasting impression of Gotham courtesy and kindliness would be made on all visitors and foreigners!”

-Burnett F. Brennan

Brooklyn, Dec. 24, 1914

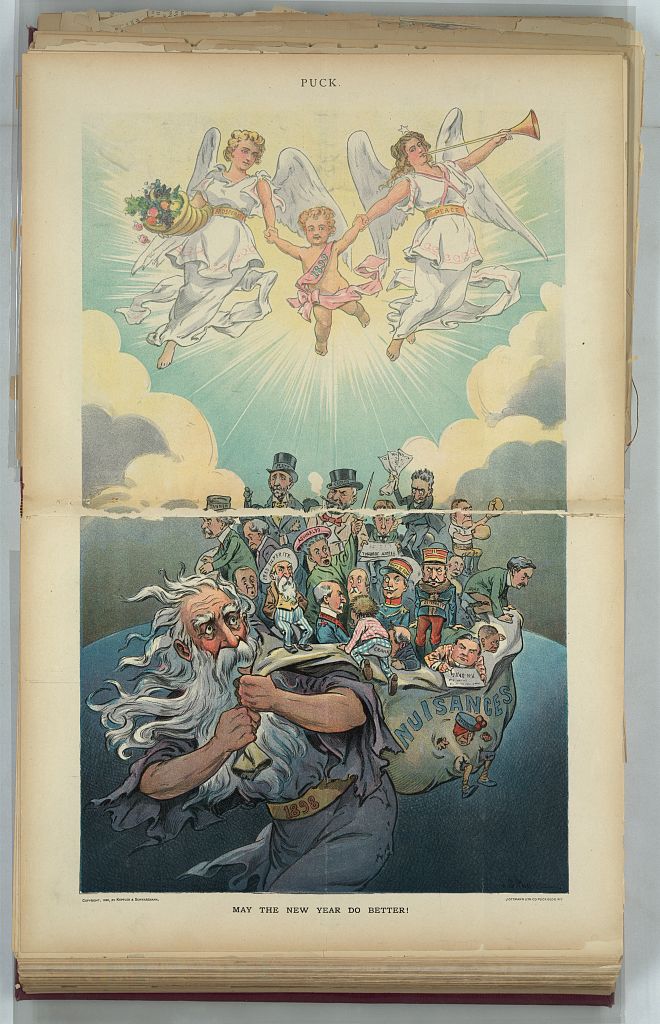

And my most favorite New Year’s resolutions reference of all is this Puck cartoon that encourages the swearing off of the following:

-bringing crying infants to the theatre

-trying to get change for large bills at the train station during rush hour

-leaving the door open after exiting a building

-violently slamming on the breaks when operating a trolley car

What about you? Are there things you would like to see others “swear off”?

What about a resolution you would like to have “engrossed” this year?

Love Victorian and Edwardian culture? You may enjoy these blog posts:

The Victorian Croquet Craze: crazier than you think

Victorian letter writing rules

Femininity in Question: Edwardian Depictions of the New Woman

I don’t do New Year resolutions, but I do a word of the year. Most of my better “resolves” have come about at some random date mid year.

Happy New Year to you~