Victorians were innovators with a deep curiosity about the natural world. They also had a real knack for creating beautiful visuals, especially to our modern sensibilities. As we saw in my look at the life of Marianne North a couple of weeks ago, their scientific explorations often ended with beautiful aesthetics that we still enjoy today, removing ourselves from the research aspect of their origin. The study of snow is no exception. As it has been snowing every few days here in Denver I thought it would be fun to stay indoors and take a look at how pretty Victorians displayed their research. Let’s stay warm and enjoy the work of Israel Perkins Warren and Wilson Bentley.

Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature by Israel Perkins Warren

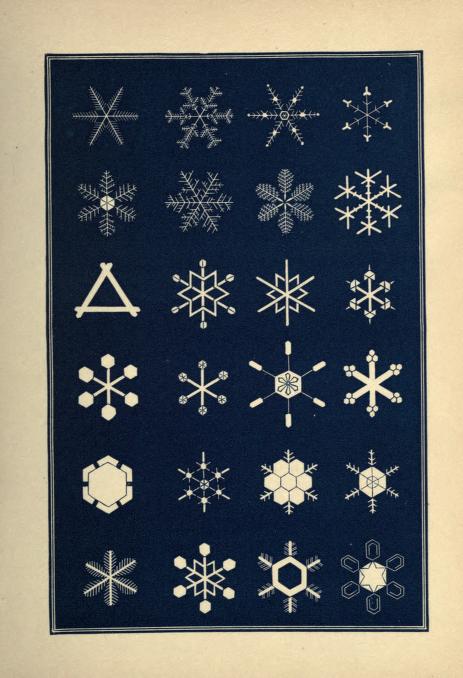

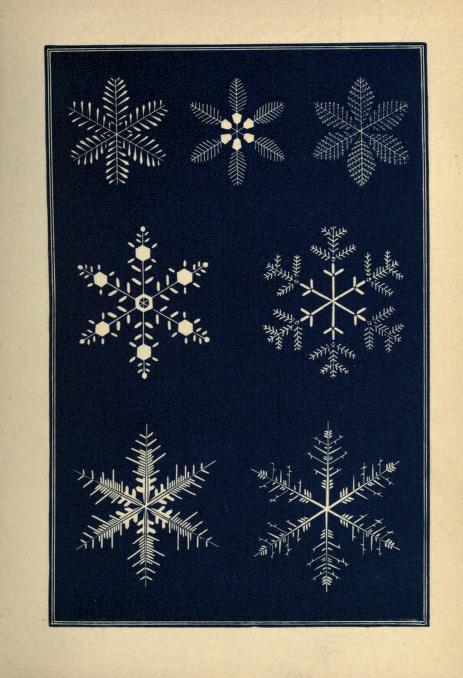

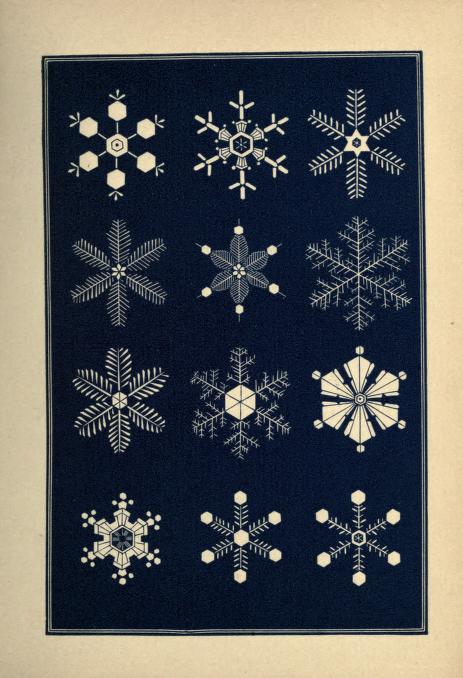

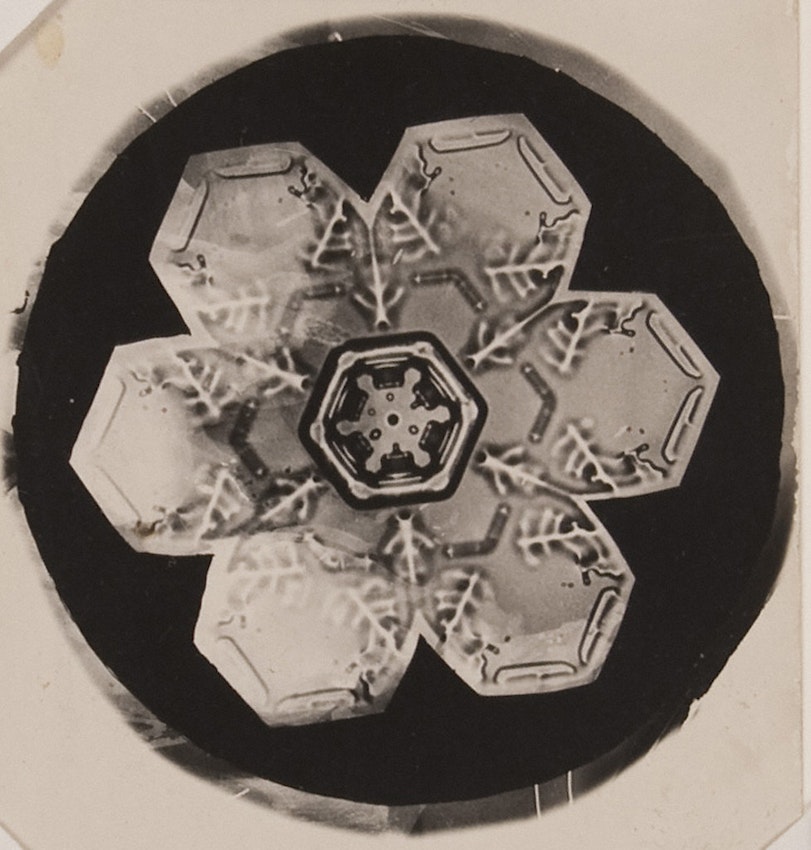

Before photographs of snowflakes could be taken people made sketches, often after catching them on pieces of black fabric. With the continual onset of magnifiers, Victorians were able to learn more about the construct of these frozen particles. Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature includes a collection of these drawings, along with scientific explanations, religious declarations, and poetry on the magnificence of winter.

Written in 1863, it is one of the most delightful books I have stumbled upon during my time writing for Recollections. The author, Israel Perkins Warren, was seemingly passionate about the topic, as seen in the introduction:

“We may be permitted to express the hope that many of our readers will examine for themselves these beautiful productions of nature. In our own climate, the “treasures of the snow” are open to all who choose to explore them; and there can scarcely be an amusement more entertaining, and at the same time instructive, than that of observing and sketching these delicate crystals.”

And in his description of watching the snow fall:

“Nowhere is snow so beautiful as when one sojourns in a good old-fashioned mansion in the country, bright and warm, full of home joy and quiet. You look out through large windows and see one of those flights of snow in a still, calm day, that make the air seem as if it were full of white millers or butterflies, fluttering down from heaven. There is something extremely beautiful in the motion of these large flakes of snow. They do not make haste, nor plump straight down with a dead fall, like a whistling rain- drop. They seem to be at leisure ; and descend with that quiet, wavering, sideway motion which birds sometimes use when about to alight. You think you are reading ; and so you are, but it is not in the book that lies open before you. The silent, dreamy hour passes away, and you have not felt it pass. The trees are dressed with snow. The long arms of evergreens bend with its weight; the rails are doubled, and every post wears a starry crown.”

Among the scientific parts of the book is Warren’s observations on the perfect symmetry of the snowflake. In a chapter titled “Perfection” he writes:

“Striking characteristic of the snow crystal is its perfection of form. Whatever the type of its structure, that type is completed with the utmost regularity and nicety. Every angle is of the prescribed size,–not a degree more or less..With a precision which art would strive in vain to excel, the pattern carried out in detail with the most exact symmetry, and in the most nicely-adjusted proportions.”

The book also includes chapters on the various emotions snow can illicit, such as gloom and gladness, as well as the various traits of snow such as power and weakness.

Scattered among the religious and scientific ponderings are charming poems about snow that I am so glad are documented, and that I also think have the makings for a lovely illustrated collection.

Snow Crystals by Wilson Bentley

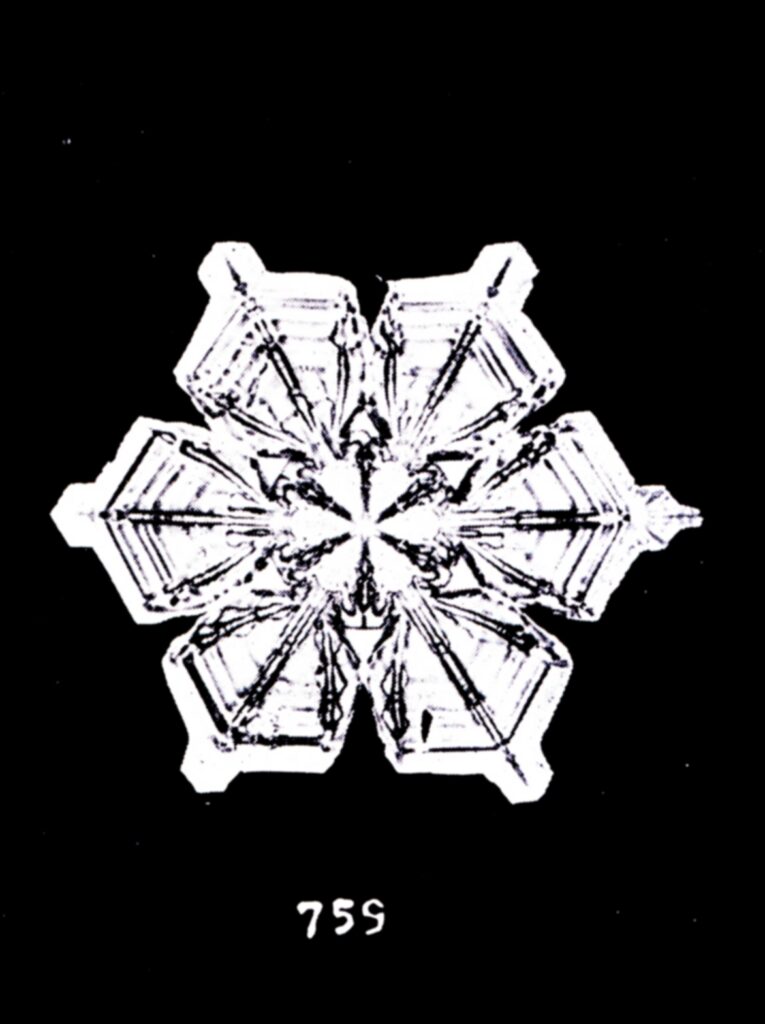

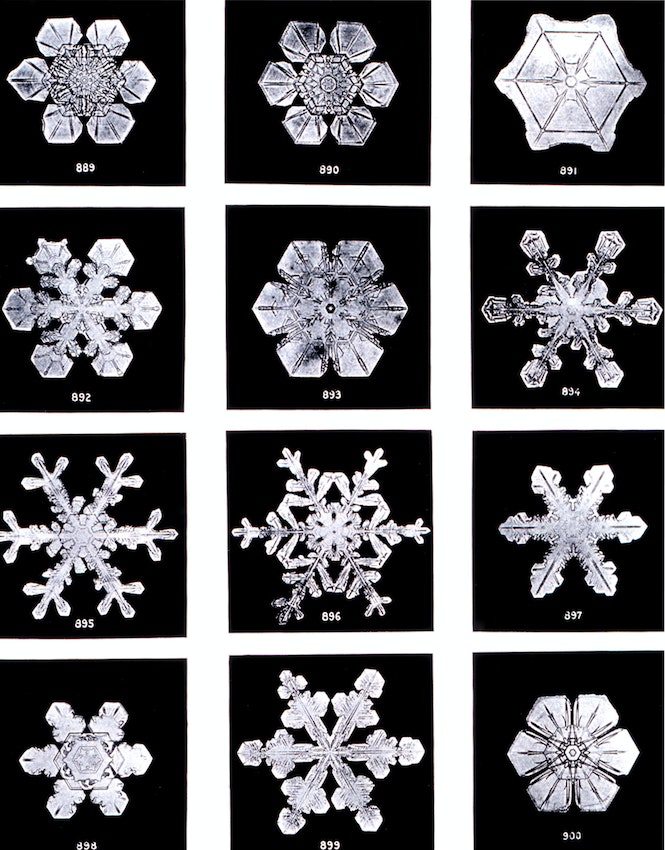

The drawings included in Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature are remarkable in their detail. I wonder if the artists could have imagined that just a few decades later photographs would be made of these intricate morsels, providing the world with an even closer look.

Wilson Bentley was born in Vermont in 1865. His mother said that he was always interested in the small things found in nature, from raindrops to butterflies. His mother, a former teacher, gifted him a microscope for his 15th birthday and he would spend the rest of his life dedicated to learning as much as possible about such things, especially precipitation.

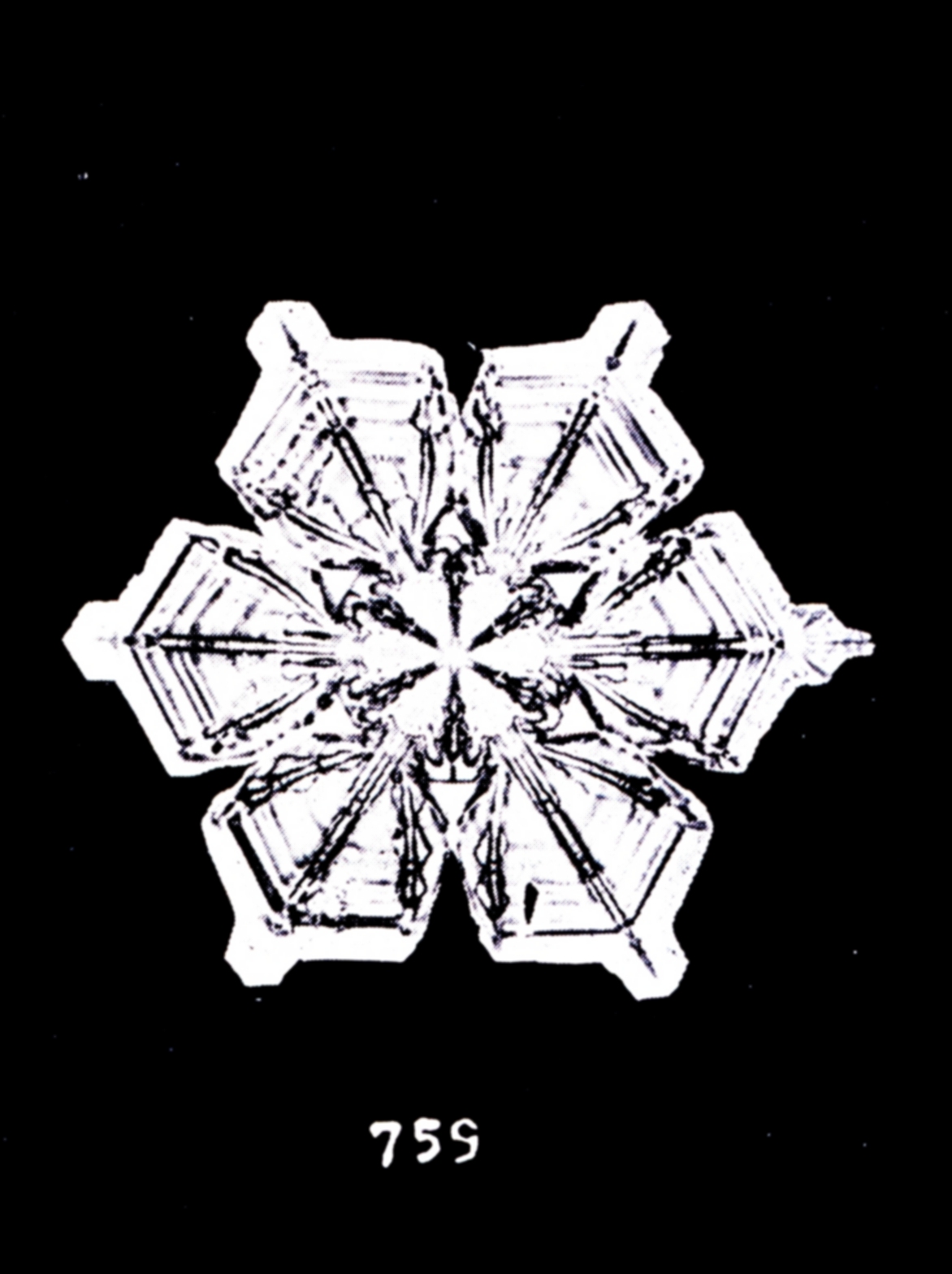

Bentley was taken by the complexity of snowflakes and wanted a view of them that was more permanent. In 1885 he had his hands on a camera, though with the medium being so new he had to experiment to figure out how to capture the image of a fleeting snowflake. Writes Just History Posts:

“On the 15th January 1885, Bentley took his equipment out in the midst of a snowstorm. He connected his camera to his microscope and stood in the cold, catching falling snowflakes. When he found one, he gently lifted it with a feather so as not to melt it and placed it under the lens of the microscope. The freezing cold of the outside air allowed the snowflake to last through the minute and a half-long exposure to take a photograph. Instant photo printing was still a long way away, so Bentley took his film inside and developed the negatives. He almost fell to his knees: at last, he had managed to take a good photograph of a snowflake, resplendent before him. “It was the greatest moment of my life”.

This experiment would make Wilson Bentley the first person to ever photograph a single snowflake. However, he assumed that others were doing the same work and amassed over 400 such photographs before his work became known by a single scholar or scientist. When George Perkins of The University of Vermont learned about the project he convinced Wilson of its importance and a book was devised.

Snow Crystals is a collection of 2,500 photographs and it is stunning. The book is still in print today.

Learn more about Wilson Bentley in the delightful book Winterlust by Brund Brunner.

More winter fun:

Staying warm in the Victorian winter

Leave A Comment