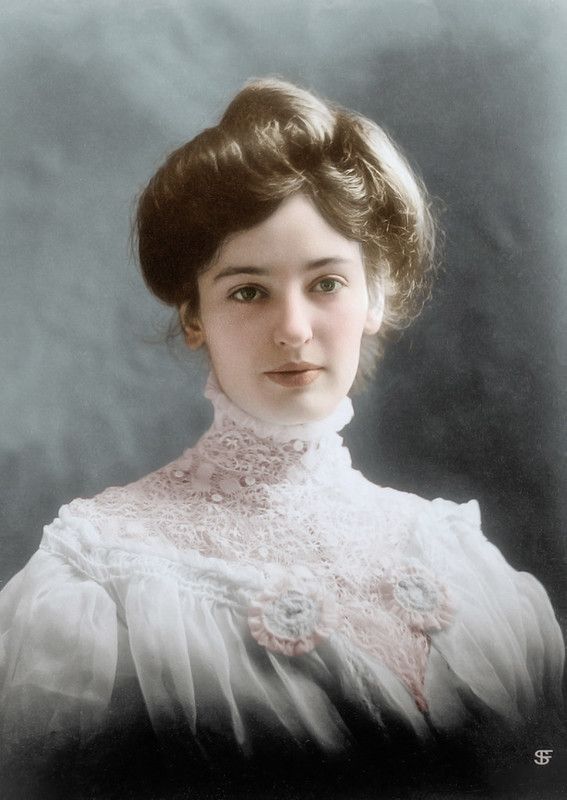

One of the first things I do when I put on makeup is to dab my cheeks with a bit of blush. I have always loved the effect and while blush has taken a back seat to eyeliner and contouring more recently, it is still a part of my most basic leaving the house routine. Maybe I just enjoy classic looks from the past, as so-called “rosy cheeks” have been sought after by women for centuries, including the Victorian era. Does that surprise you?

Last year I wrote about the Victorian obsession with shielding the face from the sun and the association between pale skin and a woman’s status in society. This obsession is well known and has led many people to believe that Victorians didn’t use makeup or cosmetics. This is far from the truth. In fact, the right color cheek was as sought after in the Victorian era as in any other, it is only the way they achieved it that was different.

Let’s take a look at how Victorian women pulled off a rosy glow in the Victorian era. It may make you extra thankful for today’s easy-to-apply options.

Victorian attitudes about cosmetics

It is well known and documented that Victorians favored the “natural” look. There are several reasons for this, including:

-A continued swing away from the decadent aesthetic of the late 18th century and early 19th century and the frivolousness associated with the time period.

-An embrace of the Cult of True Womanhood and a push to encourage women to stay in domestic roles. Manufactured cosmetics were often associated with women in the performing arts and therefore women chose to work outside the home.

-A strong association white society held between status and pale skin.

It is also believed that Queen Victoria favored a natural appearance and that English women sought to emulate her. It is possible, however, that she was responding to the larger societal trends herself.

One of the more popular etiquette books of the mid-19th century was The Arts of Beauty, Or, Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet. Ironically written by the well-known actress and courtesan, Lola Montez, it is a look at Victorian beauty standards that leaves little doubt about the pressure women must have felt to get things just right.

As for rouge, Montez echoes the general attitude of the time:

“And let no woman imagine that the men do not detect this poisonous mask upon the skin. Many a time have I seen a gentleman shrink from saluting a brilliant lady, as though it was a death’s head he were compelled to kiss. The secret was, that her face and lips were bedaubed with paints.”

One of my favorite 19th-century etiquette guides for women, The Art of Dressing Well. A Complete Guide to Economy, Style and Propriety similarly warns women:

“A fair skin is never improved, nor is a bad complexion made handsome, by the use of any of the injurious compounds sold under the pretense of “beautifying the complexion.” The best cosmetic in the world is a bountiful supply of clear water, thrown on the face with the hands, and dried upon a moderately coarse towel.”

Striving for rosy, sans rouge

Yet as much as a gentleman may shrink from a woman’s painted face, the many references to rosy cheeks in Montez’s book remind us of the double bind women were in.

“The stiff and prim city belle, encased in hoops and buckram, may well envy the agile, bouncing country romp, who, with nature’s roses in her cheeks, skips it like a fawn, and sends out a laugh as natural and merry as the notes of song-birds in June.”

The pressure to conform was a strong one, with the standard being that one took great pains to appear beautiful while at the same time not appearing to do so. As stated in the article ‘The Arts of Beauty’: Female Appearance in Nineteenth-Century British Library Newspapers’ by Michelle J. Smith:

“The overwhelming weight of the opinions of male journalists and editors weighs heavily on how female beauty is discussed in nineteenth-century newspapers. That the subject was certainly not regarded as too frivolous to consume column inches is suggested by the sheer number of articles on the subject published from 1850-1900, to take just a sample of years.”

One of these standards was a rosy cheek. Other etiquette manuals of the time show us the lengths women would go to achieve it discreetly.

DIY rosy cheeks, the Victorian way

It was the actual purchase of cosmetics that seems to have been slightly taboo in the Victorian era, not the use of products to alter one’s appearance. This seems to be understood among women during the time, as many respectable books gave tips for artificially producing color on the skin. Here are just a few of the various methods employed.

The ladies’ book of etiquette, and manual of politeness; a complete hand book for the use of the lady in polite society (1860): [sic]

Yaoulta: Take 1 ounce of white starch, powdered and sifted, ½ a drachm of rose pink, 10 drops of essence of jasmine, and 2 drops of otto of roses. Ix and keep in a fine muslin bag.

This exquisite powder is to be dusted over the face, and, being perfectly harmless, may be used as often as necessity requires. It also imparts a delicate rosy tinge to the skin preferable to rouge.

Note: I have searched and searched for the meaning behind “Yaoulta” and am yet to have information to share.

Want rosy cheeks? Head into the kitchen, but watch out for burns and blisters

Health and beauty Hints by Margaret Mixter (1910):

The mustard effect

“A girl I know, whose cheeks are naturally colorless, by using her own concoction of glycerin and English mustard, has worked up a pretty flush. And this is the way she has brought out the red: By rubbing into her cheeks a paste made of English mustard, one teaspoon of flour, and enough glycerine to form a sticky mess. The theory is simply that mustard brings the blood to the surface.

As soon as there is sensation of smarting the paste is washed off in warm water and a few drops of glycerine rubbed into the flesh to prevent irritation. Caution must be exercised in doing this that the original paste does not remain on sufficiently long to cause blistering.”

And of course, beet rouge:

Health and beauty Hints by Margaret Mixter (1910):

“Beet rouge, that was popular with our grandmothers, can be made by anyone. The raw vegetable is thoroughly washed and dried. It is then pressed against a grater until the juice is extracted, and this liquid is then mixed with starch or rice powder until the shade one wishes is attained. It is finally covered with a thin cloth to keep out dust, and set in the sun to dry. This is absolutely harmless when applied to the skin.”

The British Newspaper Archives sites another recipe for beet rouge, found in an 1890 Gentlewoman article:

“Before the beetroot is applied, Venus encourages a lengthy preparation of the face, which should be ‘gently sponged with tepid water (if possible without soap).’ After that, ‘eau de Lubin, eau de Bully, or best of all, Mason’s Essential Oil of Eau de Cologne’ should be applied, which would give ‘a very desirable feeling of freshness.’

We are still not ready, however, to apply the beetroot. The face should be dampened with ‘a fairly strong solution of alum water,’ and then powder should be applied. Venus recommends ‘Mr Mason’s Bloom of Stephanotis,’ which should be put on with ‘a piece of chamois leather, instead of the ordinary puff, as it can be rubbed into the skin, and so remain on much longer.’

Finally, Venus then advises her reader to ‘dip a rather thick camel’s-hair brush into the beetroot juice.’ The beetroot needs to have been cut up previously, and left to stand and drain for a little while. The cheek is painted with the beetroot juice as ‘desired,’ and then more powder is added (with the aid of the chamois leather), in order ‘to tone down too voyant a colouring.’”

DIY for the weekend

And if you’ve got a lot of extra time on your hands to dedicate to achieving just the right rosy look, consider this recipe from The Cyclopaedia of Practical Receipts in All the Useful Arts (1841):

Rouge, Pure: Take safflowers, any quantity; wash them until the water comes off colourless; dry, powder, and digest in a weak solution of carbonate of soda; then place some fine cotton wool at the bottom of the vessel, and precipitate the colouring matter by gradually adding lemon juice or white vinegar till it ceases to produce a precipitate. Next wash the cotton in cold water, then dissolve out the colour with a fresh solution of soda; add a quantity of finely-powdered French chalk, proportional to the intended quality of the rouge; mix well, and precipitate as before; lastly, collect the powder, dry with great care, and triturate it with a minute quantity of oil of olives, to render it smooth and adhesive.

**This is the only article which will brighten a lady’s complexion, without injuring the skin.**

Do you have any DIY home beauty tricks?

Love learning about the Victorian era? You may enjoy these posts:

The rise and fall of puffy sleeves

Thank you for reading!

So interesting and well researched!

Another winner, Janice! Very interesting some of the ingredients. I’m wondering in today’s thinking what were some of the allergic reactions! They probably wouldn’t have connected that.

My grandmother (b.1893) always told me to stay out of the Sun. Except for a teenage tanning craze, I have always tried. Seems melanoma runs in the family, so she was correct!