by Donna Klein

The other day I was talking with a friend of mine who is a nurse and the subject of Florence Nightingale came up. I thought I would write a post about her, but as I was doing my research, I became fascinated by Mary Seacole. She truly embodied the pioneer spirit; she believed in herself and she believed in making a difference.

Mary Seacole’s Early Days

She was born Mary Jane Grant, the daughter of a Scottish officer in the British Army and a free Jamaican Creole, in 1805, in Kingston. Her mother ran a boarding house in Kingston where she treated people who were ill using herbal medicines as needed. This is where Mary’s fascination with medicine began. This knowledge was passed down to her. She also had a ‘patroness’ who funded her education and training as a nurse.

Traveling

Mary possessed a love of travel, too. She visited many places; Cuba, Haiti, the Bahamas, Central America, and Britain. Through her travels, she was able to learn about and incorporate European medical ideas with the knowledge she gained in nursing school and through her mother.

Mary married Edwin Seacole, a permanent resident of her mother’s boarding house, in 1836. The marriage was short-lived, however. Edwin died in 1844.

She and her sister ran the family boarding house for a few years. They supervised its reconstruction after the great fire of 1843 in Kingston. She also nursed cholera and yellow fever patients in Jamaica and Las Cruces, Panama. Her brother owned a hotel in Las Cruces, and she helped him run it for more than two years. She also helped with a cholera epidemic in 1850, and yellow fever outbreak, both in Jamaica. She was well-known as a medical practitioner, including the treatment of knife and gunshot wounds.

The Crimean War Days

When the Crimean War broke out in 1853, British soldiers serving in Turkey came down with cholera and malaria. Mary heard about an appeal in the London Times newspaper in 1854 asking for nurses to aid wounded soldiers. She took letters of recommendation with her, but when she applied, she was turned down.

Undeterred and knowing she could make a difference, she went to the Crimea and approached Florence Nightingale about helping. Again she was turned down. Instead of going home, she went to a British bridgehead at Balaclava. Somehow, she managed to build a British hotel on the main supply road to the siege of Sevastopol. She sold food, drink and clothes to British officers and also treated medical problems. She also traveled to the front lines to visit injured troops.

After the war, Mary was left with a great reputation among the British military forces, but little money. She was nearly destitute when she returned to London. But, once her plight became known, many people, including such prominent ones as Major General Lord Rokeby, Prince Edward, and the Duke of Wellington.

Mary Seacole’s Later Days

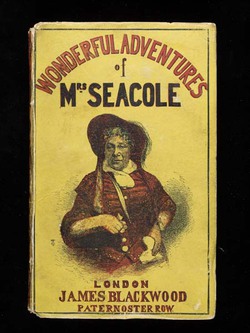

Mary Seacole published an autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, that focused on her work during the Crimean War in 1857. She was the personal masseuse to the Princess of Wales in 1870. She died in Paddington, London, on May 14, 1881.

Sources

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/seacole_mary.shtml

http://spartacus-educational.com/REseacole.htm

http://www.biographyonline.net/humanitarian/mary-seacole.html

Leave A Comment