I am still quite a fan of snail mail and look forward to using the holidays as excuses to send cards and letters to people in my life. And I do so with quite a bit of freedom. I choose my own paper, my own color of ink, and allow my personality to come through. Mail from me can’t be mistaken for mail from anyone else. Writing a letter in Victorian times was a completely different story. If one wanted to be taken seriously, they would cultivate the art of letter writing and not deviate from the standard set forth by the plethora of etiquette manuals of the time. Personality? Leave it for in-person encounters!

I knew there were proper ways to write a letter in Victorian times, but I was surprised at how strict the rules were and the amount of pressure that was put on people to adhere to them. I think I would have been quite nervous to write a letter back then!

“No accomplishment is more necessary, or of greater benefit to one’s self and others, than the cultivation of epistolary correspondence. Many friendships that night have lasted through life have been dissolved from neglect of it–many advantages lost, and many means of usefulness put out of reach.”

–The young housekeeper as daughter, wife, and mother: forming a perfect ‘young woman’s companion, 1869

It all begins with the proper selection of paper

The type of paper used for letter writing was something to be taken quite seriously in Victorian times. Apparently, it said a lot about the person sending the letter and their respect for the recipient. And if you are thinking that lovely stationery paper with delicate borders or designs may have been preferred during this era, you would be mistaken. The decorated paper was considered vulgar and in bad taste. Says Beadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen (1859):

“Letter paper (other than for business) with designs of any kind is in questionable taste, as are seals ornamented with flowers and figures. Perfectly plain paper should be preferred: it may be embossed with the writer’s initials.”

The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1856) permits decorated paper, but only for young ladies of leisure:

“The selection of paper ought always to be in keeping with the person, age, sex, and circumstanced of the correspondence. Ornamented paper, of which we have just spoken, paper bordered with colored vignettes, and embossed with ornaments in relief upon the edges, or slightly colored with delicate shades, is designed for young ladies, and those whose condition, taste, and dignity, presuppose habits of luxury and elegance.”

And How to Write Letters (1876), a very comprehensive guide to all things written correspondence states that to use coarse paper leads to coarse words and impressions:

“Both paper and envelopes should be of fine quality. It conduces to fine penmanship and perhaps inspires the writer with fine thoughts. Coarse paper, coarse language, coarse thoughts,–all coarse things seem to be associates.”

Pen and ink

Equally important was the pen and ink used. Here again, people were encouraged to err on the side of simplicity:

“Never write a letter with red ink. Indeed, it is in better taste to discard all fancy inks, and use simple black. It is the most durable color, and one never tires of it.”

1869’s The young housekeeper as daughter, wife, and mother: forming a perfect ‘young woman’s companion’ encourages readers to take the matter of pen and ink selection very seriously:

“Use good pens. Bad pens make bad writers, waste time, spoil paper, and irritate the temper. Therefore it is not economy to use bad pens because they are low in price…As few hands are alike, the best plan to find which kind of pen best suits your hand and temperament is to purchase several kinds of pens, and to try each by writing the same words upon the kind of paper which you generally use.”

“Use good ink. It is very annoying to attempt to read a letter written with pale ink, especially if the letter be upon important business, and the read is in an ill-lighted office; or worse still, if it be a love-letter, and the reader, of course, all impatience.”

Know your place

Just as important to write a letter in Victorian times was the attitude of the writer and the knowledge of one’s position in society. Much emphasis was placed on making it understood in letters that a person was aware of their place in society and also their place in the relationship with the person they were corresponding. A lot of the wording in the etiquette manuals I read uses terms such as “inferior” and “superior” when describing these relationship dynamics. For instance, How to Write Letters reads:

“The style of a letter should be adapted to the person and the subject. To superiors it should be respectful and deferential; to inferiors, courteous; to friends, familiar; to relations, affectionate; to children, simple and playful…It would be absurd to write to a schoolboy in the stately phrases of an official letter, and equally absurd to use the familiar language of love and friendship in a communication of business.”

Writing a letter with proper “style” was just as much about giving respect and commanding it. Says Beadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen:

“If you address one beneath you in education or position, do make him feel his inferiority; be polite without familiarity, as politeness is due to every man of good parts to those beneath him.”

Don’t skimp on the flattery when addressing a woman

“In addressing a lady, imply your opinion of her taste be seeking her advice on subjects which require it. Never weary of burning incense; there is an altar in the heart of woman, and even of man, always ready to receive its fragrance. The design of good-breeding is to make you agreeable to every one; write your letters so that each one reading them will be pleased and satisfied.” –Beadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen

Keep it classy

It would certainly shock a Victorian to read emails and text messages from today. Great importance was placed on using plain language in writing letters, but also avoiding phrases considered lazy, trendy, or of the common man. To read a letter was to know a person’s level of refinement. The young housekeeper as daughter, wife, and mother: forming a perfect ‘young woman’s companion’ set the bar quite high, encouraging readers to aim for Shakespear-quality wording:

“Avoid using unmeaning or vulgar phrases, as “You know,” “You see,” “So you see,” &c. But do not strive to write “fine” language. Write good, strong, expressive English, such as you will find in Shakespeare and the best writers. Many personal affect grandiloquent language, ponderous but poor. With them everything is splendid, superb, delicious, &c.” (sic)

From How to Write Letters:

“Avoid slang words and phrases, such as “too thin,” “won’t wash,” “over the left,” “you bet,” etc. Young people are apt to pick them up in the street and elsewhere and use them unconsciously. In such cases they indicate simply a want of taste; but in most cases the mark the man or woman of low associations and vulgar ideas.”

I have a feeling that the “slang words and phrases” the author mentions may have much different meanings today!

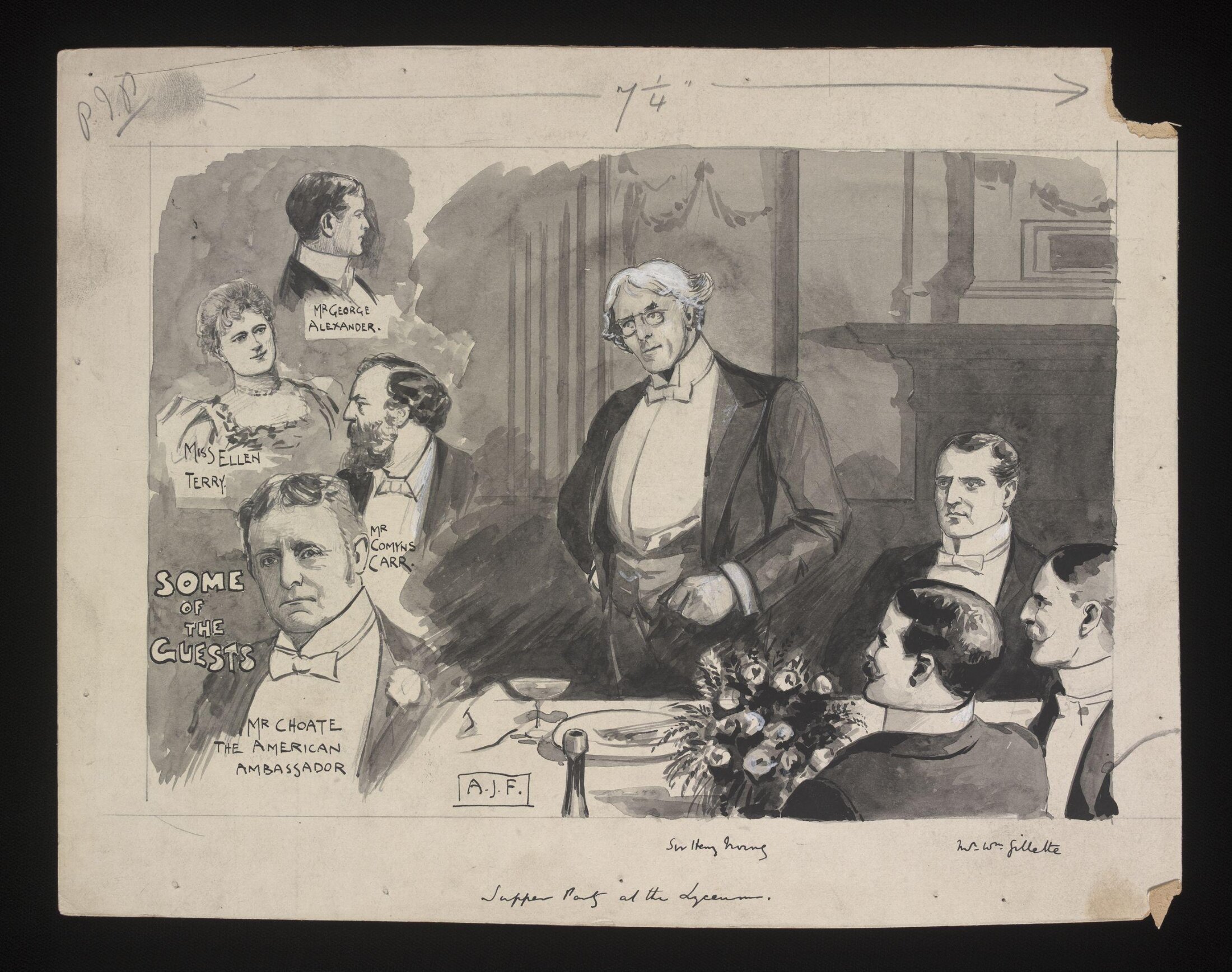

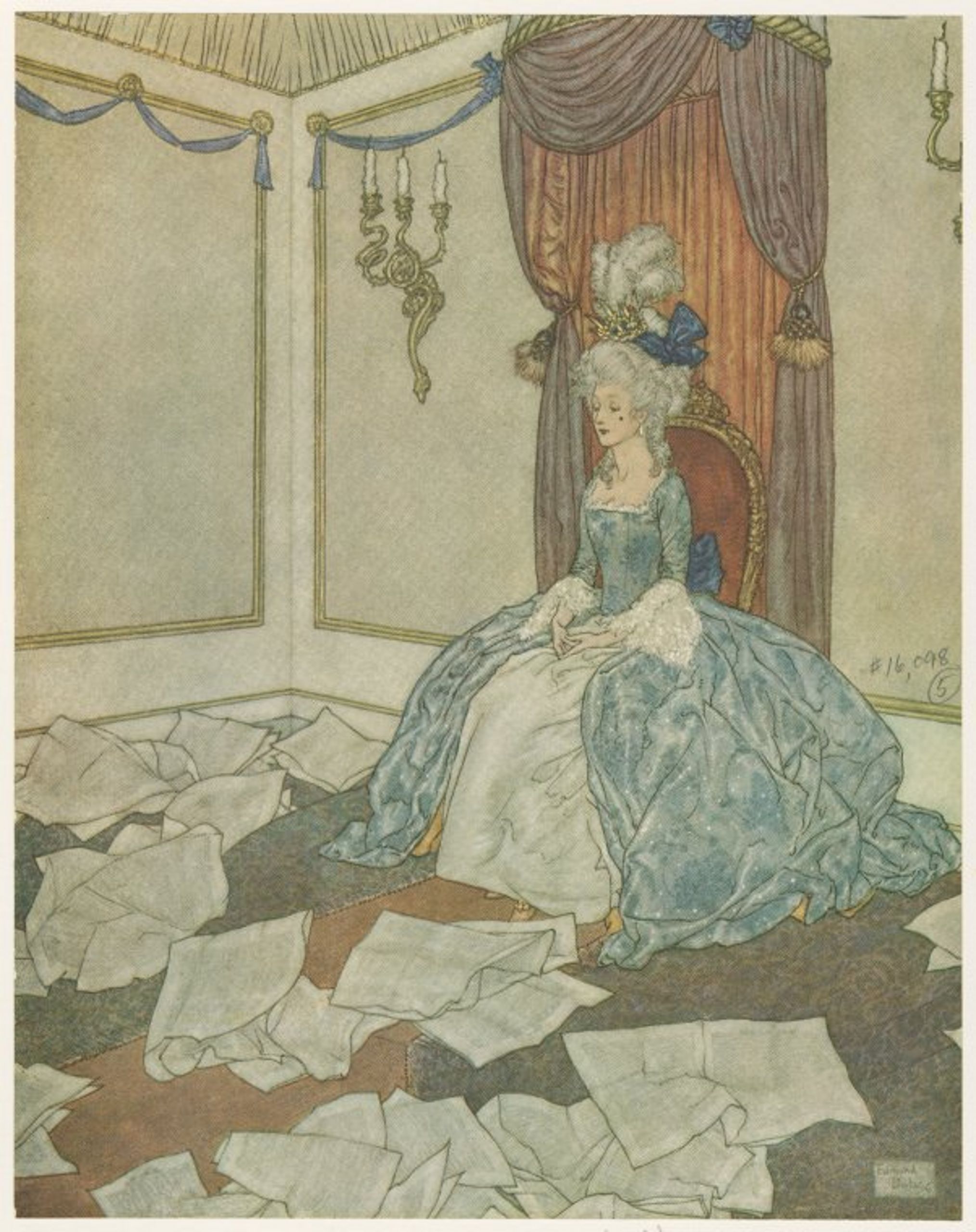

Leave nothing to chance! Templates for Victorian letter writing

Included in any Victorian etiquette manual that discussed letter writing were sample letters for various occasions. These letters provide such great insight into how people interacted with each other during the time and how close people kept their cards to their chests. They show how much times have changed. Today people are quite comfortable expressing emotions of all kinds in their writing. In Victorian times there were very clear guidelines about communicating about even the most sensitive of topics.

Take, for instance, my favorite of the template letters I found while researching for this post. The occasion for the letter is listed as “A lady on receiving from her suitor an apology for some offense”:

DEAR SIR:

The acknowledgment of your error, contained in the letter I have just received, does honor to your feelings, and serves to convince me that, though you had swerved from that good sense which is the usual guide of all your actions–accidentally, I believe, I cannot now think designedly–you are still the same both in head and heart, the man of honor which I have ever been won’t to esteem you.

That you had offended me, I have not attempted to disguise from you; but the apology which you have made is so satisfactory that it dissipates from my mind that feeling of displeasure which your late conduct had given rise to.

Henceforth let us banish this painful subject from our recollections; the sensible and manly letter which you have this day sent has reconciled you to me, and determined me to subscribe myself.

Yours, still sincerely,

Catharina Van Brunt

This letter tells us so much about Victorian courtship and custom. There is clearly an expectation that the “offending” party sends a letter of apology, but also that upon doing so, it be forgotten.

I wonder what sort of offense this letter would have been used for!

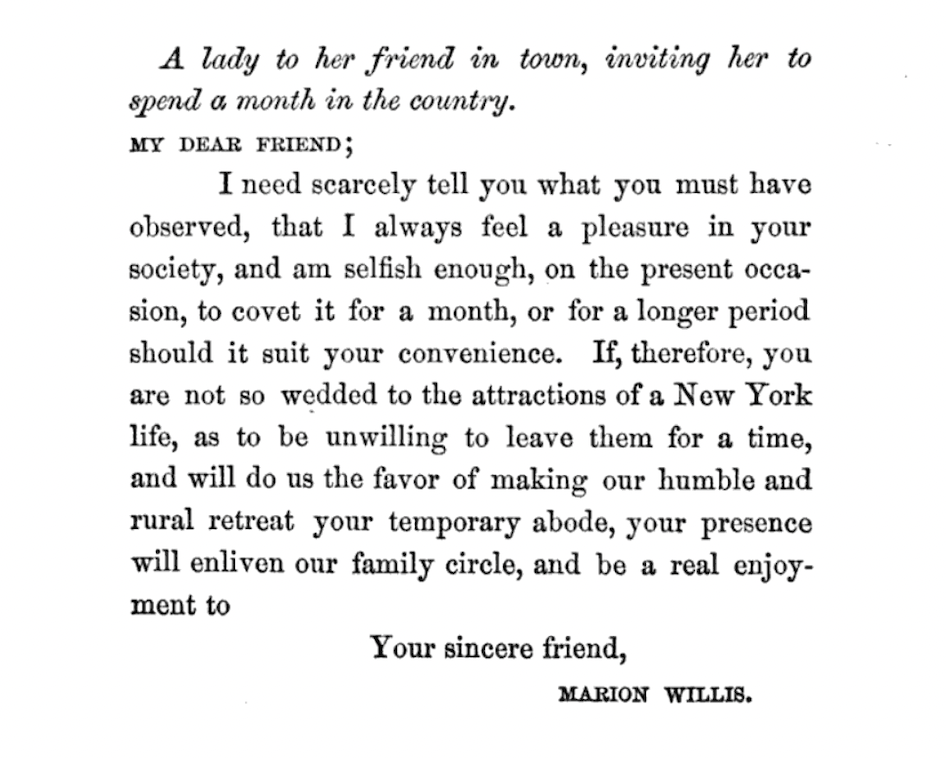

I also noticed that the sample letters show a lot about the lifestyle that the middle and upper classes enjoyed during the Victoria era. There are many templates to extend social functions of all sorts and of all lengths. The one below is a template for inviting a friend away to the country for an entire month.

Other topics I found in the manuals I searched:

-Letter to a friend on the evil consequences of a love of dress

-From a mother to her newly-married daughter on domestic economy

-Letter accepting a proposal of marriage

-Letter declining an offer of marriage

-Letter on the advantage of simplicity, and cultivating a contented spirit

-Invitations to balls

There is much more to be said on Victorian letter writing! Stay tuned for future posts on the topic!

Learn more about Victorian culture:

Vinegar Valentines: a look at Victorian cruelty

Before selfies and text messages there were friendship books

I agree! Thank you so much for reading!

I’d love for letter writing to come back in popularity. It would be so nice to have a Pen Pal. I’ve lost the skill and art of writing a letter to a friend. A book like you showed (in a modern sense) would be most helpful. Thank you for sharing such interesting examples!

Thank you so much for being a reader!

Dear Ms Formichella,

I am writing to thank you for this post and to convey my admiration for your blog.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, my wife and I became interested in Victorian dance, and I discovered Recollections while researching period attire. Since then our dancing has been curtailed for obvious reasons, but I continue to enjoy visiting your blog. Thank you for your gracious edification of readers like me. If I have remained a silent beneficiary until now, perhaps the topic of letter writing has proven irresistible. Thank you again.

Sincerely,

A. N. Admirer

I agree! I send them pretty regularly still and I love to hear from people when they get them. Let’s not let the practice die!

Thank you so much for being a reader! I love to write letters too! Sometimes I feel like I’m the only one, but people sure enjoy receiving them!

Loved reading this! Bit of a far cry from today’s communication! I have been a letter writer for 60 years and run a Penpal Club – yes, they DO still exist! I write approximately 1000 letters a year and publish a magazine called Rainbows too.

Marjorie, rainbows5534@hotmail.co.uk

I love this. I too appreciate real letter writing though probably much less formal than what would have been expected. There is still something special in sending and or receiving a hand-written letter.