Last weekend I picked up the April copy of Real Simple. The theme for the issue is naturally, spring cleaning. It got me thinking about how this tradition has been around for so long and wondering how much I could find in Victorian household manuals on the topic. I am also striving to use more environmentally friendly products in my home, and thought I might learn something as well. Victorian spring cleaning did look a lot different than it does today. Without a lot of the modern conveniences and supplies that we now use, it was a lot more involved. And, they had some great ideas that I think we can still use today.

Victorian household manuals were highly specific on how to clean each and every part of a house, from floors to lamps to windows and beds. Remarkably, the books recommend different methods for nearly each item in a home that could be cleaned.

Getting ready to do some spring cleaning of your own? I have pulled a lot of ideas from a few great household manuals to give you a true look inside preparing a home for spring in the Victorian era.

It all about the attitude

It appears to me that spring cleaning was taken rather seriously by many Victorian households, though many had mixed feelings about it. In 1857 writer Sara Payson Willis Parton wrote of the ritual:

“‘Spring cleaning!’ Oh misery! Ceilings to be whitewashed, walls to be cleaned, paint to be scoured, carpets to be taken up, shaken, and put down again; scrubbing women, painters, and whitewashers, all engaged for months ahead, or beginning on your house to secure the job, and then running off a day to somebody else’s to secure another. Yes, spring cleaning to be done; closets, bags, and baskets to be disemboweled; furs and woolens to be packed away; children’s last summer clothes to be inspected (not a garment that will fit all grown up like Jack’s bean-stalk); spring cleaning, sure enough. I might spring my feet off and not get all that done.”

In 1848 writer Susan Fenimore Cooper wrote that spring cleaning was a necessary evil in life, though did say that it was often worth it in the end:

“It must be confessed, however, that after the great turmoil is over – when the week, or fortnight, or three weeks of scrubbing, scouring, drenching are passed, there is a moment of delightful repose in a family; there is a refreshing consciousness that all is sweet and clean from garret to cellar; there is a purity in the neighborhood, the same order and cleanly freshness meet you as you cross every threshold. This is very pleasant, but it is a pity that it should be purchased at the cost of so much previous confusion – so many petty annoyances.”

And before you go embracing the notion that Victorians were far more stuffy and strict about cleanliness than we are today, think again. Household manuals also taught about having a positive attitude about domestic tasks. The book The expert cleaner : a handbook of practical information for all who clean houses, tidy apparel, wholesome food, and healthful surroundings, published in 1899 reminds readers that while cleanliness is important, one should maintain a laid back attitude about it:

“The extremely neat housewife is not an agreeable person. Her nerves are too keenly alert in watching for possible defects in her own or another’s housekeeping. Her sensitiveness is shown in her temper and in her tongue. Too much neatness, because of the anxiety attending, becomes injurious to the mental faculties, and so lessens the vitality and those energies by which the housewife should make her surroundings sweet and agreeable.”

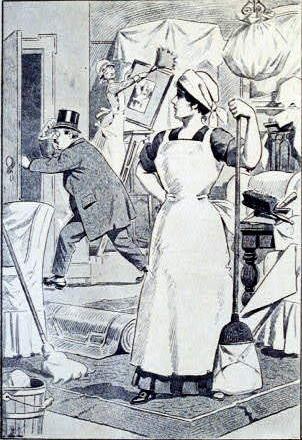

Victorian methods for a deep spring clean

There was not a household item or fixture that Victorians didn’t have a very specific way to clean. The household manuals from the time prescribe so many specific methods and supplies that it is no wonder books needed to be kept handy to keep it all straight. After all, there was no multi-purpose spray!

Before you start your spring cleaning, make sure to take note of these very peculiar, and very Victorian, cleaning hacks.

Gilded picture frames

“Freshen up the colour and shine of gilt picture frames by going over them with a soft brush dipped in water in which three or four onions have been boiled for about an hour.”

Mind Your Manors

Sweeping:

Keep it a secret!

“While sweeping, keep all doors shut, that the dust may not spread. And let those who are not active assistant in the operations know as little as possible of what is going on; have no brooms and brushes there to proclaim it, and no water-pails and dust pans standing about to endanger people’s shins.” The expert cleaner

Wallpaper

“If a good wall paper is soiled, it may be refreshed by rubbing it lightly with a piece of bread-crumb; this too, is best done by straight long strokes.” [sic] The expert cleaner

Deep cleaning bedding

“If one sunny day in the year, at least, all bedding could have a good airing out-of-doors, it would be very beneficial: a feather bed put in the sun for a day will have received almost as much benefit as if it had been sent to be cleaned and steamed. A feather should be put into all the screwholes and crevices of a bedstead, to clear it of dust; and if there is a suspicion of any unwelcome visitors, the feather should be dipped frequently in turpentine.” The expert cleaner

The stove

The young housekeeper as daughter, wife, and mother has an entire narrative about a young maid learning the complex task of cleaning a stove, and it may help you use up that pesky stale beer:

“”Well Jane,” said her mistress, “I am glad to see you have conquered the difficulty of lighting the fires. Now, I think it adds very greatly to the comfort and beauty of a fire-place that the stove, fire-irons, and fender should all be bright and clean. I will not, as I promised, teach you how to make them so.

And after preventing fingermarks by placing wood panels and paper, and rolling up the carpets, it is time to begin cleaning the stove:

“moisten some black-lead with a little stale beer, if there is any; if not, water will do. Then with the small round blacking-brush put the lead over every part that is to be blacked. Be careful not to black over the bright stell ornaments. In many stoves the ornaments are made to slip in and out, and then it is better to remove them before using the black-lead.”

Windows

An 1860’s issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book stresses the importance of making sure a seasonal cleaning gives special attention to the windows of a home:

“The windows of the house sometimes reveal the character of the occupants in a way not to be misunderstood. Where they are dirty, filled with cracked panes, or disfigured with slovenly blinds, we may conclude, without much risk of mistake, that those who dwell within are not models of order and cleanliness. On the other hand, well-kept windows give an appearance of respectability and a sense of propriety and comfort which are highly gratifying. Drapery is to a room what dress is to the human figure, and, like dress, its style may be such as to suit every taste and every pocket.”

And how to wash them? Got any black tea on hand?

An 1879 issue of Country Gentleman reads: “…Dry whiting will polish the glass panes nicely; and we find weak black tea with some alcohol the best liquid to wash the glasses. For a few days before the cleansing takes place, save all the tea grounds; then when needed, boil them in a tin pail with two quarts of water, and use the liquid on the windows. It takes off all dust and fly specks. If applied with a newspaper, and rubbed off with another paper, they look far better than if cloth is used.”

Floors

A little milk should do the trick!

“When a floor has been polished it may be kept in order without much trouble. Many new things are advised for keeping the floor looking nice, but nothing is better than this: Take a flannel cloth, and saturate it in sweet unskimmed milk; with that wipe over the floor whenever it needs cleaning or brightening.” The expert cleaner

Sweet odors: a Victorian recipe for rose potpourri

The expert cleaner Included a variety of recipes for potpourris and other mixtures that add a sweet odor to the home. My favorite is “A Rose Jar,” which I do believe would leave a room smelling quite divine – if one had the patience to see it through. Because it is written in a manner that may be hard for modern readers to easily follow and use, I have broken down the steps for this Victorian DIY for you here.

- In the early morning gather the rose petal of some sweet-smelling variety.

- Let them remain spread out in some cool place, stirring them until they are free of the dew, which may take one or two hours.

- Do this each morning until the entire jar is filled. Let stand for ten days, stirring each morning.

- Take a glass fruit jar of the size desired, and put in the bottom of it two ounces of coarsely-ground cloves, the same amount of broken allspice, the same of broken cinnamon, and one grated nutmeg.

- Then put the rose leaves in the jar on the spice, and let the mixture stand for six weeks with the lid closed as tight as possible.

- Once it has been sitting for six weeks, it is ready to be used. Simply remove the top from the jar for a few moments to sweeten the room.

Will you be using any Victorian cleaning methods in your home this spring?

Thanks for the suggestion, Mea!

I use tea water on my windows.- it works very well. Used to use newspaper too but it’s getting harder to get newspaper nowadays. Now I have to use a microfiber cloth…it’s not as good as newspaper.

Your spring cleaning blog gave a wonderful chuckle to our volunteers at the Old Colorado City History Center in Colorado Springs! We have all concluded that we would prefer to be in the museum than face spring cleaning at home!

1800s wallpaper was remarkably hard to clean because it was mostly not water-resistant – it was literally paper, and sometimes embossed with designs, so it wasn’t flat. Using bread to clean such papered walls is a method that pops up throughout the century’s housekeeping tricks, because lightly wiping down with a piece of fresh bread removes some dirt and dust without damage. Later, companies started to produce “dry cleaners” for papered walls, notably in a putty form. Once such manufacturer was Kutol. By 1910 or so, wallpaper was being produced that was similar to linoleum, making it easier to wash with water. Kutol’s putty like wall cleaner was remarketed as a toy for children… Play Dough.