Author: Christine Skirbunt

In today’s digital age, it’s not uncommon to hear concerns about the impact of violent video games, explicit music lyrics, or provocative TV and films on young minds. But this pattern of blaming popular media for societal ills isn’t new. Back in Victorian England, Penny Dreadfuls – cheap, sensational fiction aimed primarily at working-class boys – were at the center of a similar moral uproar. Described as “Britain’s first taste of mass-produced culture for the young” and “the Victorian equivalent of video games” (Wikipedia), these publications were accused of corrupting the youth, inciting crime, and undermining societal values.

But what exactly were Penny Dreadfuls? And were they really as dire to society as Victorians made them out to be?

The Rise of Penny Dreadfuls

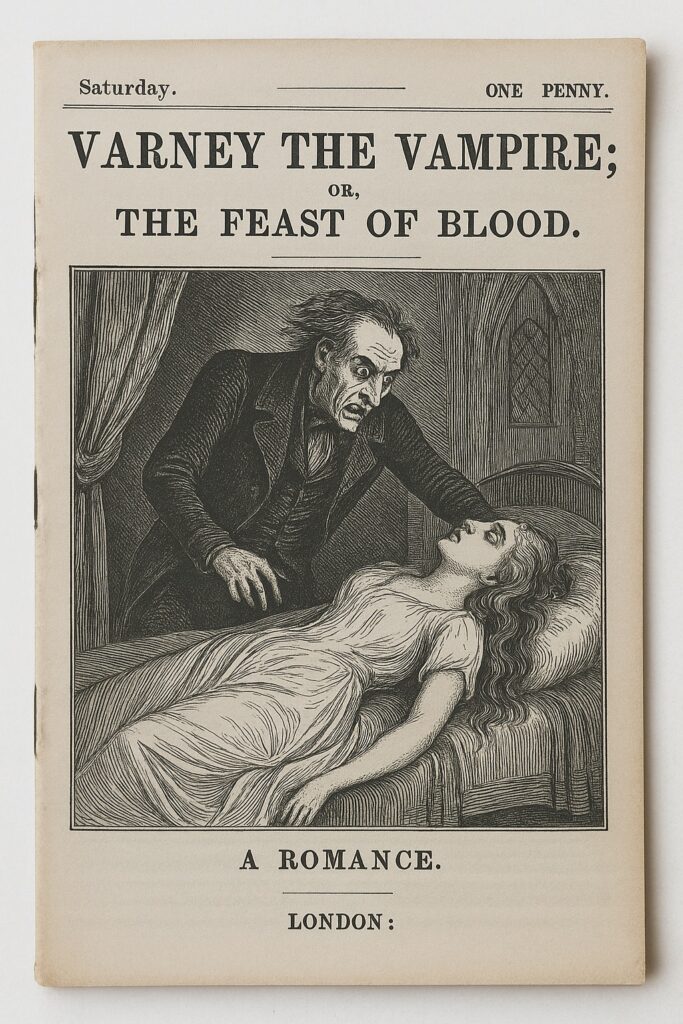

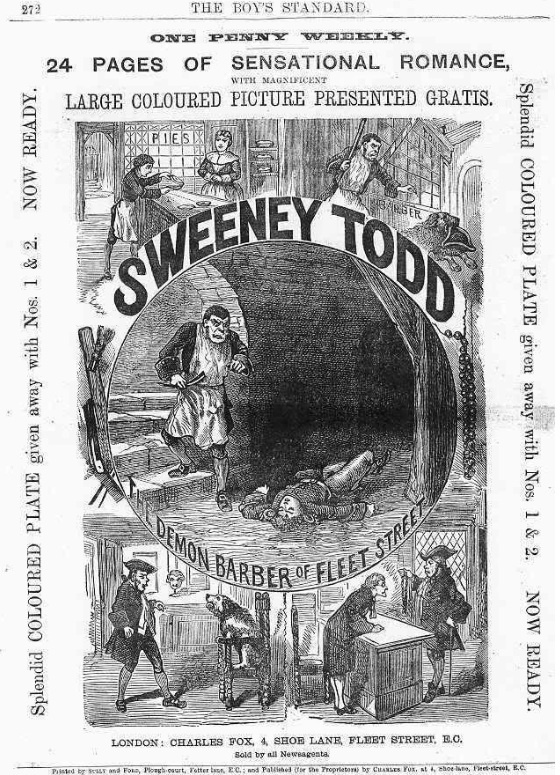

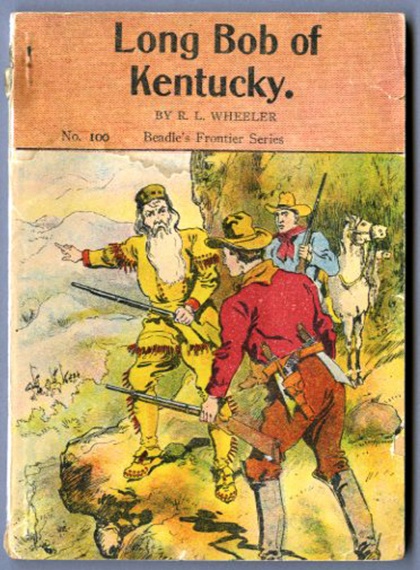

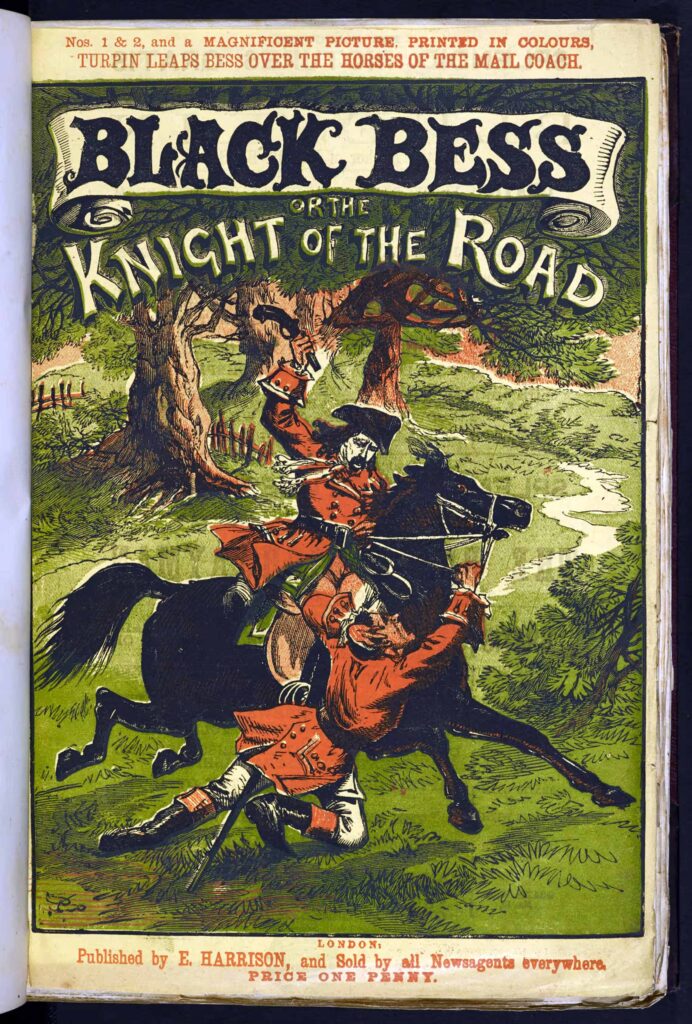

The first known Penny Dreadful appeared in 1836, titled The Lives of the Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, &c. At the time, such stories were called “Penny Bloods” due to their lurid, sometimes violent content. The term “Penny Dreadful” didn’t gain traction until the 1840s. These tales featured highwaymen, pirates, detectives, and supernatural creatures. Among the most famous were Varney the Vampire – a story that introduced many of the tropes still found in vampire fiction today (including fangs!), and The String of Pearls: A Domestic Romance, which introduced the world to Sweeney Todd. The title may have promised domesticity, but the story was anything but.

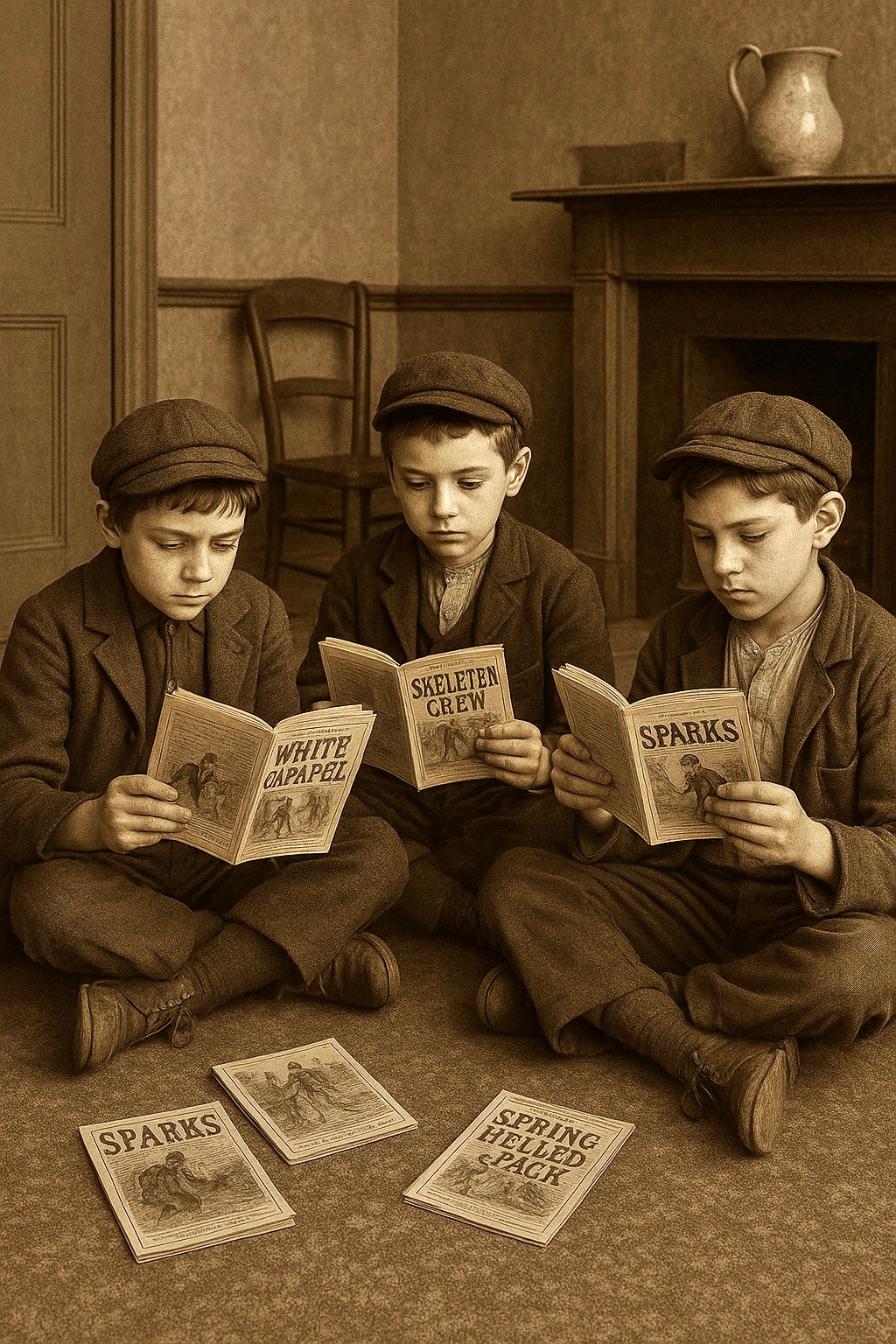

Inside, the text was often printed in double columns to maximize space on cheap thin, gray paper (Penny Dreadfuls: History). Early covers were plain and text-based, but by the 1860s, editions featured eye-catching black-and-white woodcut illustrations that depicted violence, supernatural themes, or thrilling cliffhanger moments. Their format and price made them accessible to the masses. For comparison, serialized novels by authors like Charles Dickens sold for a shilling – twelve times more than a Penny Dreadful. And at about 5” x 8” in size, they were also conveniently foldable – perfect for slipping into the back pocket of a working boy’s trousers to read at leisure.

As literacy rates rose and the working class gained access to affordable entertainment, the popularity of these stories soared – especially among boys. But not everyone was pleased. Many Victorians saw this trend as dangerous. To them, Penny Dreadfuls “gave a frightening intimation of the uses to which the laborers of Britain could put their literacy,” while “fantasies of wealth and adventure might foster ambition, discontent, defiance, a spirit of insurgency. There was no knowing the consequences of enlarging the minds and dreams of the lower orders.” (Penny Dreadfuls: The Victorian Equivalent of Video Games)

Middle- and upper-class Victorians were determined to keep the lower classes “in their place,” and they saw Penny Dreadfuls as a threat to the social order.

Moral Outcry in Victorian England

Critics argued that Penny Dreadfuls were a corrupting influence on impressionable youth, especially boys. Francis Hitchman, a British journalist and vocal opponent of the genre, famously called them “the literature of rascaldom,” expressing his belief that they glorified criminal behavior and undermined societal values (The Shocking Tale of the Penny Dreadful). In Hitchman’s mind, and the minds of many other Victorians, boys who read such stories were being groomed for a wayward life of crime – from petty theft to outright murder.

But what was really happening was this: the poor had finally been taught how to read in newly state-funded schools, but not what to read. The backlash against Penny Dreadfuls was less about moral corruption and more about controlling access to knowledge and imagination, and by extension, maintaining social control over the working class.

The Victorian media eagerly linked Penny Dreadfuls to real-life crimes. They seemed especially fixated on the crimes of children and teenagers, reporting on them obsessively. This only heightened public fear surrounding the cheap little books.

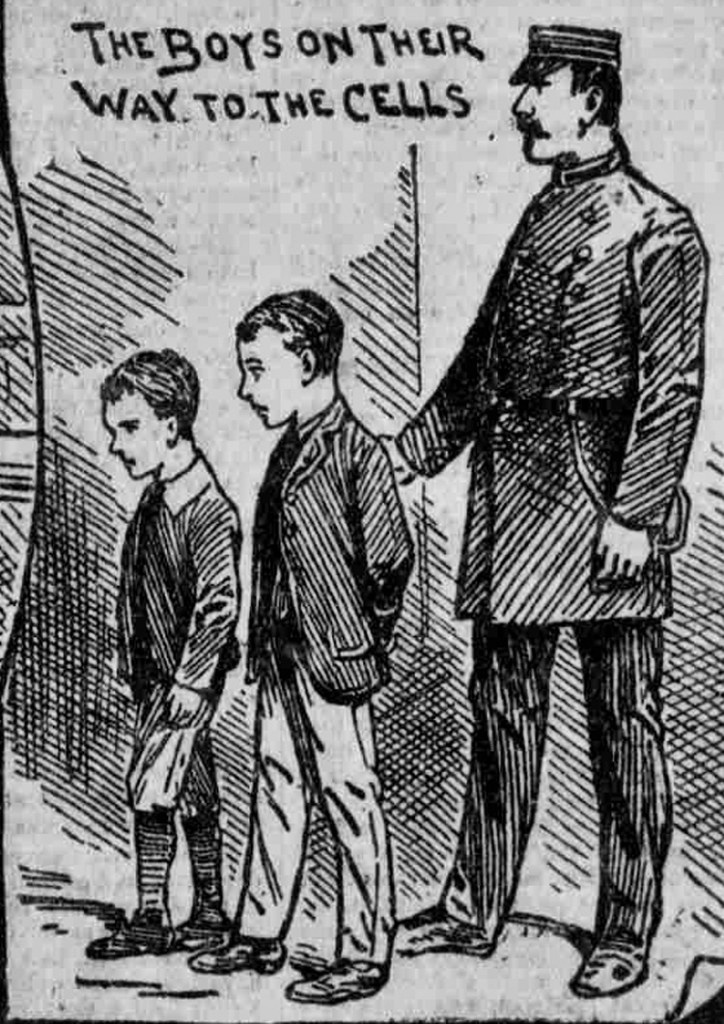

In 1888, mounting concern led to an official inquiry into the supposed connection between Penny Dreadfuls and youth crime. It failed to find any evidence that the stories directly caused criminal behavior. However, authorities noted that many boy offenders had copies of Penny Dreadfuls in their bedrooms. This fact that was seized upon as pivotal, rather than coincidental. What was conveniently ignored was that these publications were found in most boys’ bedrooms across Britain.

Despite the inquiry absolving Penny Dreadfuls of criminal influence, the media continued to vilify them. For example, in 1892, the suicide of a 12-year-old boy was attributed in the press to “temporary insanity, induced by reading trashy novels.”

The Coombes Brothers Case

In 1895, Victorian England was once again rocked by a sensational case: this time involving murder. And once again, Penny Dreadfuls were dragged into the spotlight.

On July 17, 1895, the body of Emily Coombes was discovered in her bedroom in a modest East London home. She lived there with her two sons, Robert (13) and Nathaniel (12). When the police investigated, they found a collection of Penny Dreadfuls in the parlor, and these were quickly entered into evidence at the inquest.

The press latched onto this detail. The story captivated Victorian society (much in the same way a fictional Penny Dreadful captivated young boys) and reignited the debate over juvenile crime and the influence of sensational literature. The case became a lightning rod for moral panic, despite the complexities of the boys’ home life and psychological state being far more relevant than the reading materials they had on hand. (Penny Dreadfuls: The Victorian Equivalent of Video Games)

The Blame Game

Much of the attention surrounding Robert Coombes’ motive for stabbing his mother – while Nathaniel was present but not directly involved – focused on the boys’ collection of Penny Dreadfuls. To many, the explanation was simple: it had to be the books. Surely only literature that depraved could drive two young boys to commit such a heinous crime against their own mother.

But this was a convenient narrative and one that spared Victorian society from examining the much more uncomfortable truth: the emotional and psychological distress that Robert was in with no one to turn to for help. The books provided an easy answer, but not the correct one.

In reality, it was the family dynamics that played the role in Emily Coombes’ death, as became increasingly clear during the boys’ trial. Testimonies revealed that Emily Coombes was a deeply disturbed woman. Neighbors and relatives described her as emotionally unstable, prone to hysterical outbursts, and frequently violent toward her sons. With their father absent, Robert and Nathaniel were left to fend for themselves under the care of a woman clearly unfit for motherhood and with no mental health support system or societal safety net to intervene to help the family.

Robert testified that he lived in fear, both for himself and for Nathaniel. He believed their mother might one day kill them. Eventually, he said, they felt they had no other recourse. So, he acted preemptively, desperately believing it was the only way to protect his brother and himself.

Robert was found guilty but declared insane and committed to a hospital where he stayed for 17-years. Nathaniel was acquitted. After his release, Robert moved to Australia, served with distinction in World War I, and from all accounts, lived a quiet life until his death in 1949.

Patterns of Moral Panic

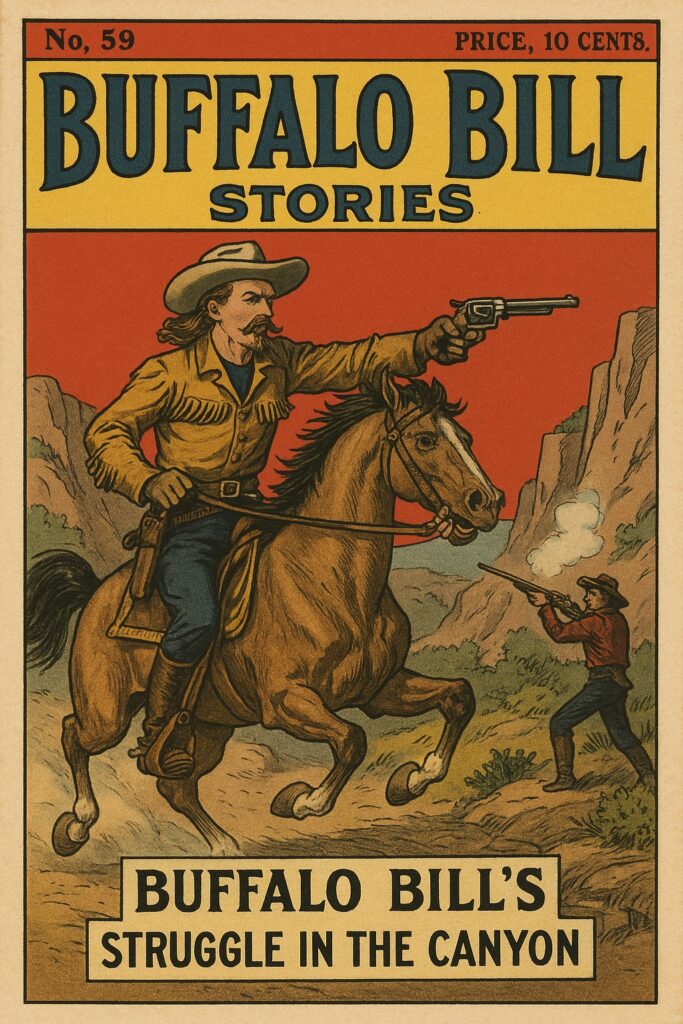

The backlash against Penny Dreadfuls (and their American counterparts, Dime Novels) is part of a larger, recurring pattern of moral panic. Every few decades, new forms of popular media are blamed for the corruption of youth and the unraveling of society. And this didn’t end with Victorian fiction.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the same cycle continued:

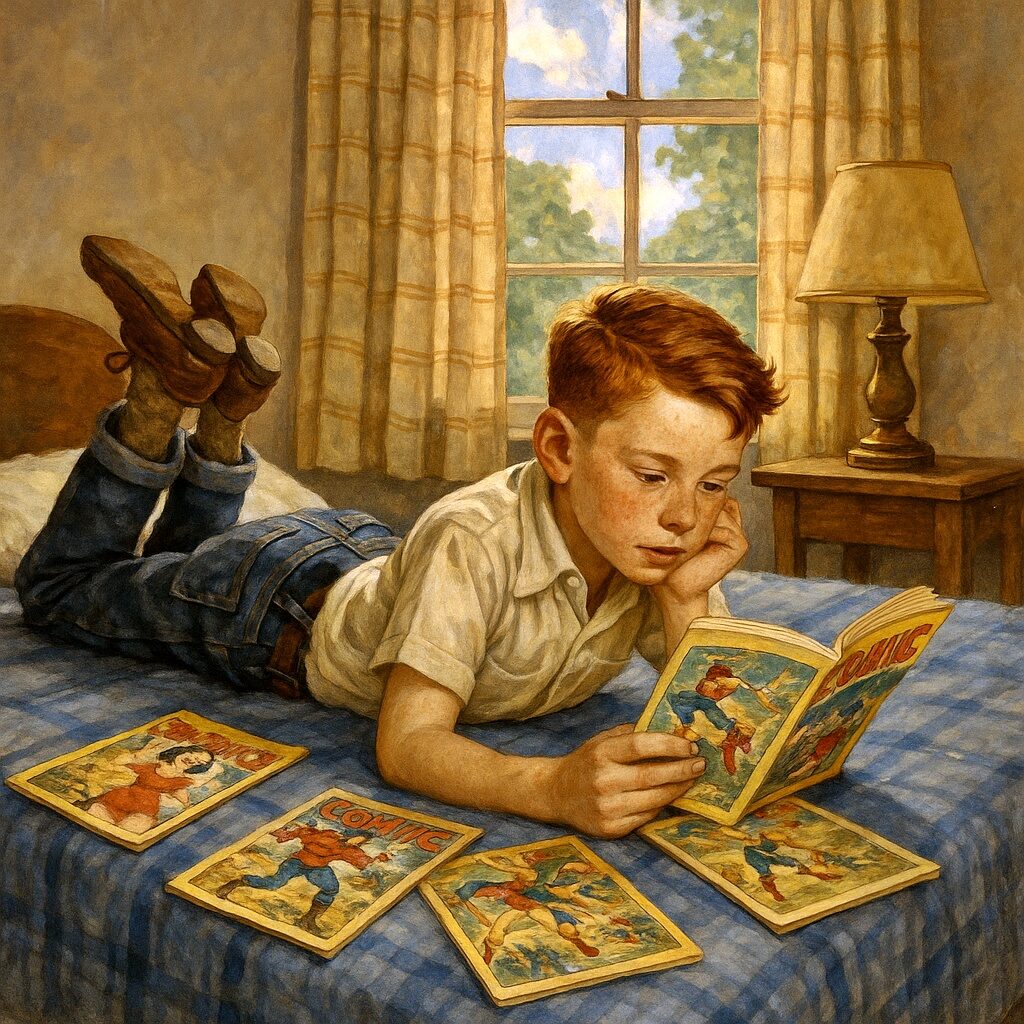

Comic Books

- In 1954, psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham published the highly influential Seduction of the Innocent, in which he claimed comic books were responsible for juvenile delinquency, sexual deviance, and anti-social behavior. Sound familiar?

- His book sparked the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, televised for the American public, where comics were grilled much like Penny Dreadfuls had been.

- To avoid government censorship, comic book publishers created a self-regulating body: the Comics Code Authority (CCA). Under its strict guidelines, comic books could not include:

- Excessive violence

- Sexual innuendo

- Profanity

- Disrespect toward authority figures (like teachers or clergy)

- Vampires, werewolves, or zombies

- And, most importantly: the good guy must always win.

- Comics that passed inspection bore the CCA seal on the cover to reassure parents that the content was wholesome.

The Blame Evolves: Radio, Television, and Film

As new forms of entertainment emerged throughout the 20th century, each in turn became the latest scapegoat for adults’ anxieties about juvenile behavior, violence, and moral decline. Much like Penny Dreadfuls before them, radio, television, and movies were met with suspicion, alarm, and attempts at censorship.

Radio

Radio introduced the first modern form of storytelling that didn’t require a book, and that alone was enough to cause a stir. Critics worried that passive listening would make children lazy and distract them from reading (but of course, only the approved kinds of reading). Radio dramas, especially crime and suspense programs, were accused of glamorizing criminal behavior.

Television

Television was accused of “dumbing down” the youth. It didn’t matter what was on: westerns, detective shows, even cartoons. All were blamed for promoting aggression, disrespect, and inattentiveness. This argument persisted for decades and eventually led to the creation of the TV Parental Guidelines rating system in the 1990s.

Film

Hollywood didn’t escape the crosshairs either. In 1934, the Hays Code was introduced. It was a sweeping set of morality guidelines imposed on film studios. To earn the Production Code Administration seal of approval (which was essential for theatrical release), a film had to omit:

- Profanity

- Nudity

- “Suggestive dancing” (whatever that meant)

- Interracial relationships

- Homosexuality

- Ridicule of the clergy (yes, that again)

Much like the Comics Code that would come two decades later, the Hays Code was designed to reassure the public that popular culture would remain morally upright – at least on the surface.

Video Games

When video games hit the mainstream, they were quickly cast in the same villainous role. Games were blamed for promoting violence, desensitization, and antisocial behavior. Even today, they are still used as a convenient scapegoat following tragedies.

But just like Penny Dreadfuls over a century earlier, video games only provide an easy answer to much more complex problems – problems rooted in social systems, mental health, trauma, and access to care.

The Last Laugh

These examples highlight society’s recurring tendency to blame emerging forms of media for complex social problems. But in many cases, the media in question has had the last laugh:

- Comic books? Publishers began ignoring the Comics Code Authority in the 1970s, and by the early 2000s, it was rendered officially powerless.

- Television? Few people today give more than a passing glance to the TV rating system, choosing instead to stream whatever they like.

- Films? The Hays Code was abandoned in 1968, replaced by the MPAA rating system, which allowed filmmakers to freely explore themes previously banned or censored.

- Video games? Though still an occasional scapegoat, they’ve become fully mainstream. The generation that grew up playing them is now raising children of its own and those parents don’t see games the way that past generations did.

Ending the Stigma

The history of Penny Dreadfuls and how their legacy has echoed through comics, television, film, and video games, reminds us that Victorian fears laid the foundation for modern moral panics. The concerns were never just about crime or violence. They were about control, class, and the unsettling idea that the working class was not only learning to read but dreaming bigger because of it.

To middle- and upper-class Victorians, Penny Dreadfuls didn’t just threaten to corrupt morals, they threatened to disrupt social order. The stories invited boys from modest homes to imagine themselves as adventurers, rebels, even heroes. That alone was subversive. Understanding this early backlash helps us see a pattern: what scares one generation often empowers the next. And while the tools of storytelling have changed, the anxieties haven’t.

References:

Hephzibah Anderson. (May 2, 2016). “The shocking tale of the penny dreadful.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160502-the-shocking-tale-of-the-penny-dreadful

Kate Summerscale. (April 30, 2016). “Penny dreadfuls: the Victorian equivalent of video games.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/30/penny-dreadfuls-victorian-equivalent-video-games-kate-summerscale-wicked-boy

N/A. (n.d.) “Penny Dreadfuls.” Penny Dreadfuls. https://dfordreadful.wordpress.com/history/

N/A. (n.d.). “Penny dreadful.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penny_dreadful

Images:

- · “Comic Books – 1950s.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “The Coombes Brothers.” Robert Allen Coombes. https://www.jack-the-ripper-tour.com/generalnews/robert-allen-coombes/

- “Buffalo Bill Dime Novel.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Long Bob of Kentucky Dime Novel.” Dime Novels and Penny Dreadfuls. https://bpsc.library.ualberta.ca/collections/dime-novels-and-penny-dreadfuls

- “Varney the Vampire Penny Dreadful.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Victorian Boys Reading Penny Dreadfuls.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/(

- “Black Bess Penny Dreadful.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Sweeney Todd Penny Dreadful.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

Further Reading:

“Robert Allen Coombes.” Richard Jones. https://www.jack-the-ripper-tour.com/generalnews/robert-allen-coombes/

“Penny Dreadfuls in Victorian England: On its Origin & Importance.” High On Books. https://highonbooks.co/penny-dreadfuls-in-victorian-england-essay/

‘But what was really happening was this: the poor had finally been taught how to read in newly state-funded schools, but not what to read. The backlash against Penny Dreadfuls was less about moral corruption and more about controlling access to knowledge and imagination, and by extension, maintaining social control over the working class.’ A tale as old as time, clearly! Is there anything the wealthy won’t do to maintain power? A silly question indeed.

Perfectly written piece with keen insights on top of well researched history. Bravo!

Beautifully summarized.