Author: Christine Skirbunt

A Ritual in Green

Taking a delicate sugar cube, you place it on a slotted spoon, balancing the spoon atop a glass filled with a beautiful green liquid. Slowly, you then pour ice-cold water over the sugar cube either via a carafe or a small tabletop fountain and watch as the clear, sugary trickle into the glass transforms the absinthe from a jewel-like emerald to a soft, cloudy opalescence. This is the louche, the moment the Green Fairy awakens.

For centuries, drinkers have sworn there is magic in this transformation, something otherworldly in the way absinthe shifts before your eyes. But for just as long, the world has battled over whether that magic is good or bad.

But What Is Absinthe, Really?

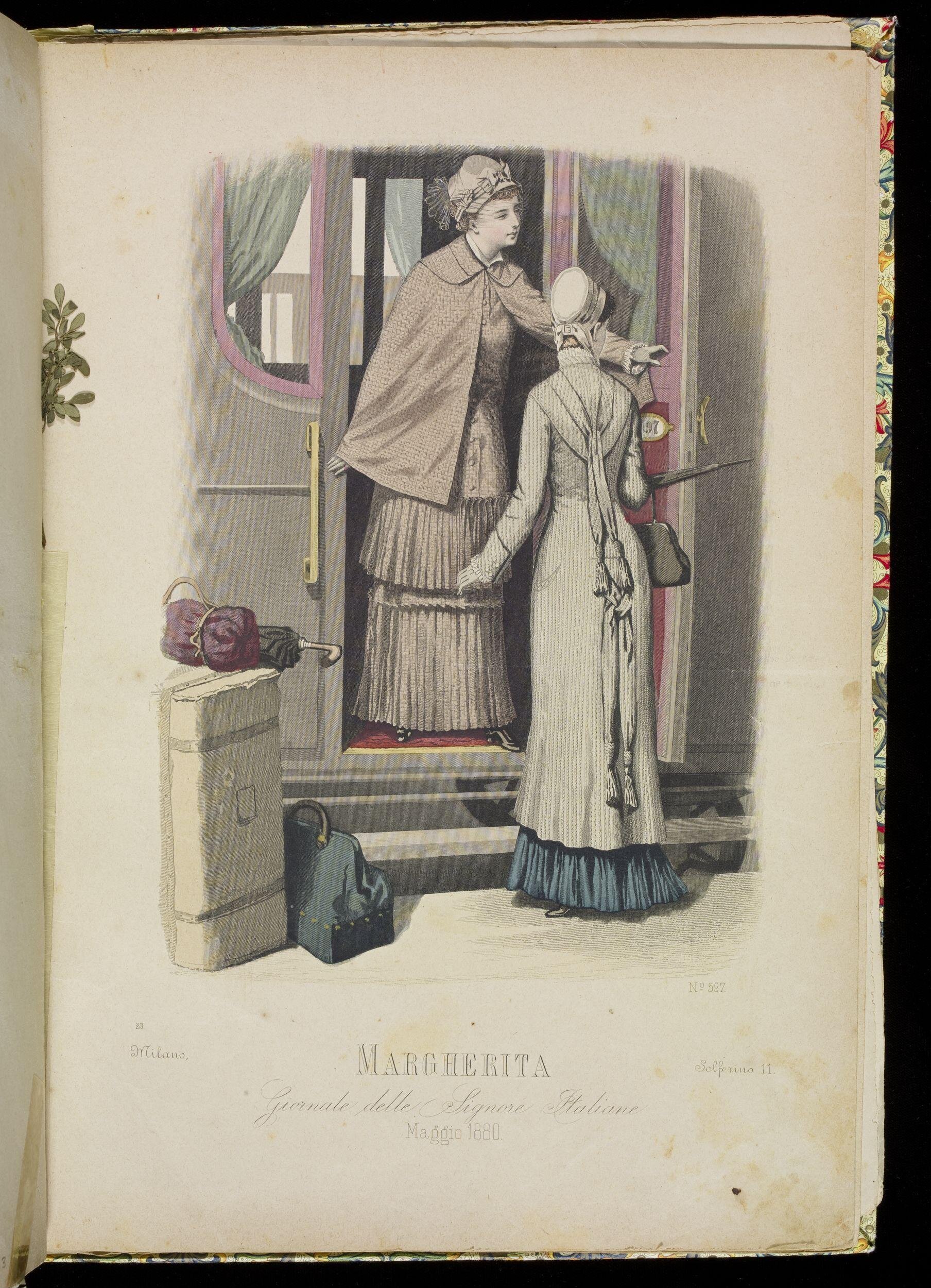

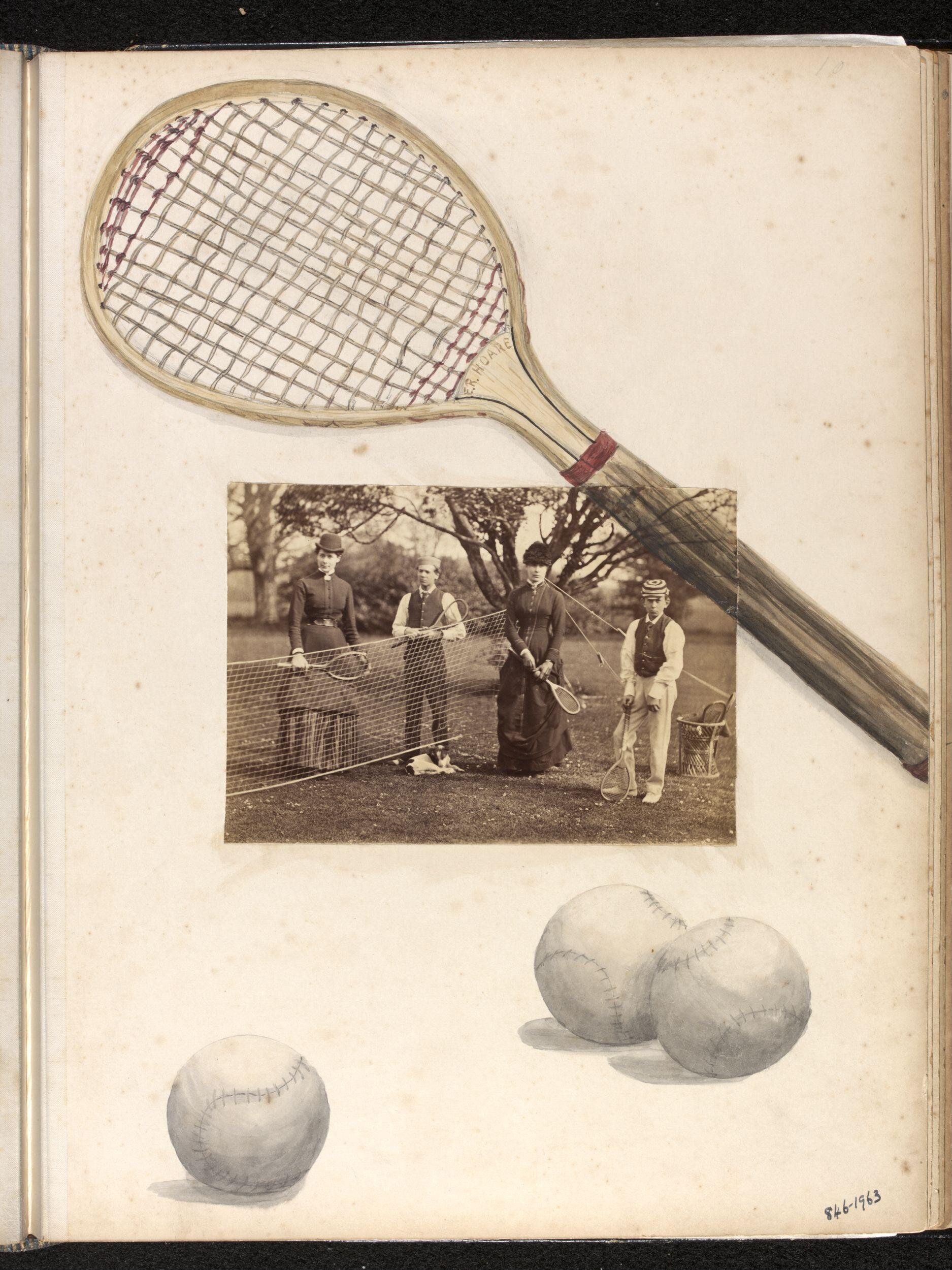

The peak of the Absinthe Drinking Era was during the Belle Époque (circa 1870–1914), especially in France. Absinthe became immensely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly among artists, writers, and the bohemian crowd in Paris.

Absinthe is an anise-flavored spirit distilled from wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), green anise, and fennel—the “holy trinity” of absinthe’s signature taste. Unlike pastis or ouzo, real absinthe is not liqueur as it is not bottled with sugar. Traditionally, it is bottled at high proof (45-74% ABV) and is meant to be diluted with cold sugar water until it turns cloudy—thanks to the essential oils within right before consumption.

Drinking absinthe properly requires a few essential tools:

- Sugar Cube – optional, but almost always preferred.

- Absinthe Glass – a specially designed glass with a reservoir to measure the spirit.

- Slotted Spoon – this rests atop the glass, allowing the sugar cube to dissolve into the drink.

- Ice-Cold Water – poured drop by drop from a carafe or fountain for the perfect louche.

However, if your only exposure to absinthe has been via Hollywood, such as in the film Moulin Rouge where the drink is set on fire before consumption, you have been terribly misled. The flaming absinthe ritual is entirely fictional, a stunt born in the 1990s to hide and distract from the fact the customer was drinking a fake—a drink with little to no real absinthe ingredients in it. True absinthe is never meant to be incinerated and to do so would not only ruin the drink, but it is historically inaccurate. It never happened in the Belle Époque era.

A Spirit Born of Medicine and Mystery

Absinthe’s origins trace back to late 18th-century Switzerland, where it was first marketed as a digestive medicinal elixir. Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French physician living in Switzerland, is often credited with its creation, though some argue it was the Henriod sisters, local herbalists, who first distilled wormwood into a curative tonic. Others say Ordinaire told the sisters his recipe before his death. Whichever version is true (if any), by the early 1800s, absinthe had moved from apothecaries to cafés and bars, particularly in France, where soldiers who had been stationed in Algeria (1844-1847) had been prescribed it to prevent disease with the belief it could make unclean water drinkable.

When these soldiers returned home, they brought their newly acquired taste for absinthe with them, and soon, it became a Parisian staple. By the mid-19th century, absinthe was everywhere—from the bohemian cafés of Montmartre to the grand boulevards of the Belle Époque. The 5 o’clock hour became known as l’heure verte—the Green Hour—when workers and intellectuals alike would gather to sip their beloved Green Fairy.

The Artists and Poets of the Green Fairy

Absinthe was more than just a drink; it was a muse, whispered about in poetry and swirled into paintings. Among its most famous devotees were:

- Oscar Wilde – the Irish playwright was known for his razor-sharp wit and his love of absinthe.

- Charles Baudelaire – the dark romantic poet whose absinthe-fueled nights inspired Les Fleurs du mal and famous for saying, “Be drunk always!”

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – living in the center of bohemian Montmartre, the artist carried a cane filled with absinthe.

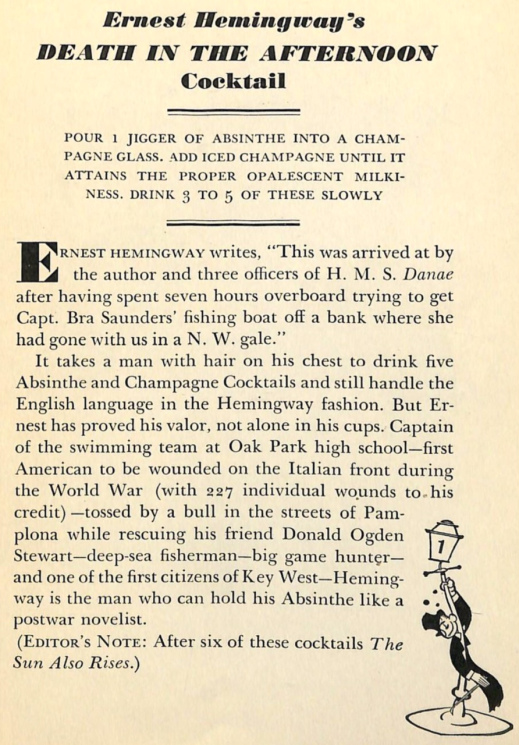

- Ernest Hemingway – created the absinthe-and-champagne cocktail Death in the Afternoon (Wikipedia), and frequently had his literary characters imbibe absinthe.

These writers, artists, and dreamers found inspiration in the swirling, heady effects of absinthe—though whether it enhanced their genius or merely accompanied them on their way is still debated.

Absinthe’s Unusual Geography: Where It Was and Wasn’t Popular

Absinthe’s stronghold was France and Switzerland, where it was consumed widely in both bohemian circles and by the working class. It also had a firm foothold in Spain, particularly in Barcelona, where it was embraced by artists like Pablo Picasso.

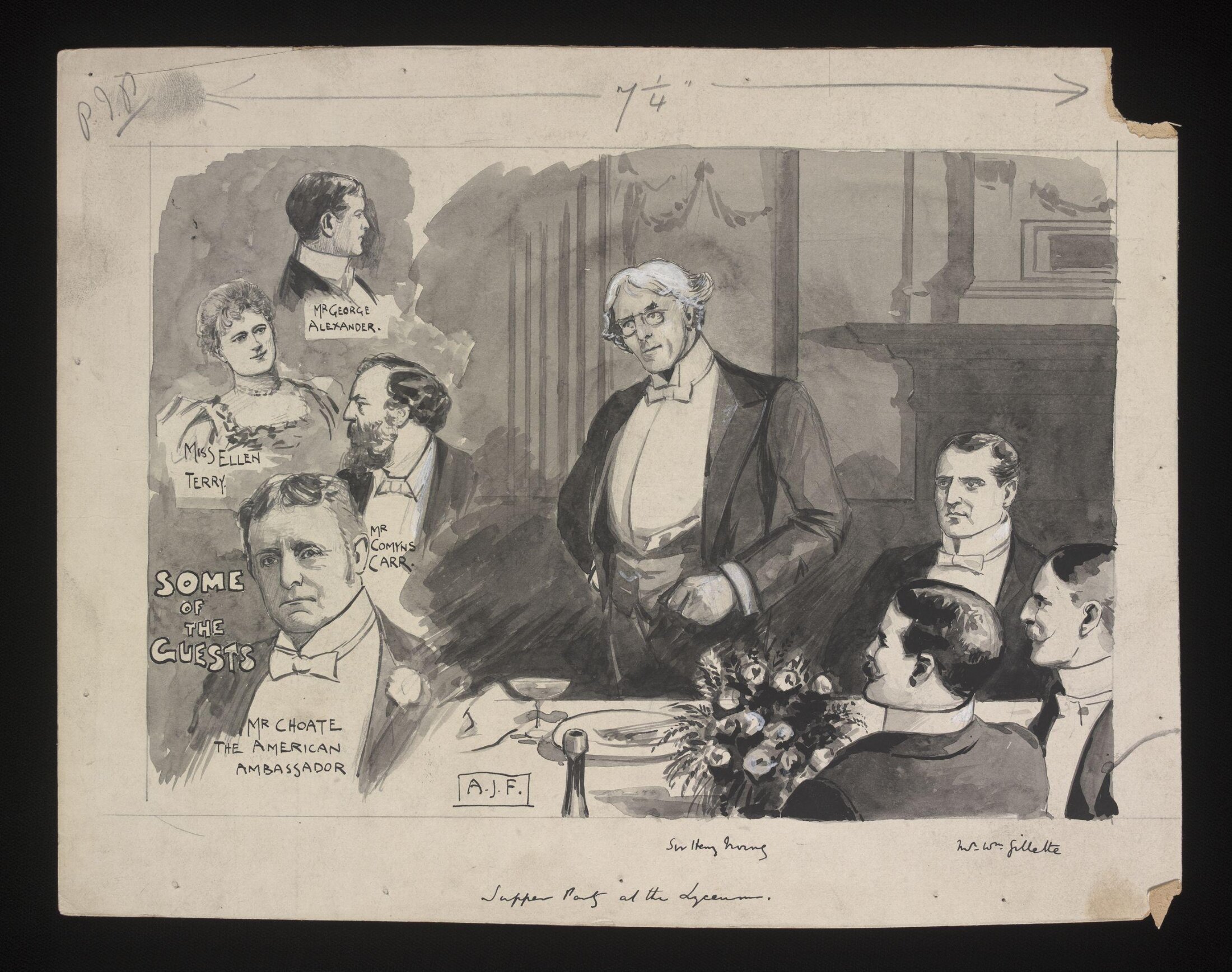

However, England never truly embraced absinthe. The British preferred gin and ales while absinthe never caught on in pubs the way it did in French cafés. Adding to this, the tight-laced English Victorians fully believed the slander that it was a drink that could be ruinous due to rumors of its hallucinogenic properties. America, on the other hand, had a quiet but dedicated absinthe fanbase, especially in New Orleans, where it was welcomed by the heavy French influences of the city.

The Smearing of Absinthe: Wine, Temperance, and Degas’ Scandal

As absinthe grew in popularity, the French wine industry panicked. Phylloxera, a louse infestation, had devastated French vineyards, making wine expensive and less available. Meanwhile, absinthe was cheaper, stronger, and beloved by the masses. When the wine industry began to recover, absinthe had supplanted wine as the national drink. Seeking to reclaim dominance, the wine industry helped fund anti-absinthe propaganda, painting it as the cause of moral decay and madness. Their assault was relentless.

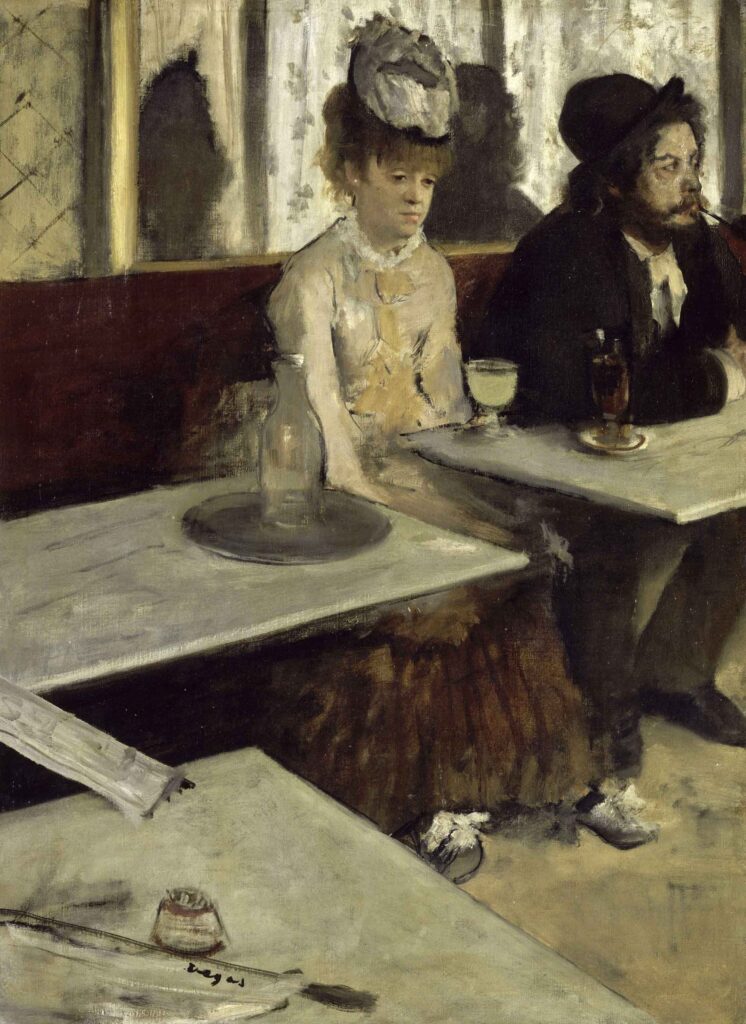

In an odd alliance, the temperance movement joined the wine industry and together they seized upon absinthe as a convenient scapegoat for society’s degeneration. A particularly infamous example is Edgar Degas’ painting L’Absinthe (1876), which depicted a solemn woman sitting over a glass of the drink. The painting seems very innocuous to the modern viewer, but in the 19th century it was considered scandalous, an example of absinthe’s ruinous effects, and was removed from public view for decades. When L’Absinthe was shown again, this time in England in 1893, Victorian society considered it “an abomination of morality.” (Wittels, 2017) Today, it is recognized as a masterpiece of Impressionist social commentary. (Wikipedia)

Alcoholism vs. Absinthism: A Manufactured Fear

Absinthe’s vilification introduced the idea of “absinthism,” a supposed syndrome of hallucinations, madness, and criminal behavior different than that of alcoholism. However, modern science has debunked absinthism as a myth—the symptoms were no different from regular intoxication. The real issue was not the wormwood in the drink, but the cheap, adulterated “absinthes” some suspect producers sold, which contained toxic additives like copper salts and antimony to enhance color. Overindulgence in other alcohols also played a role, as did laudanum and morphine being so common in this era that they were basically socially acceptable.

The Green Fairy’s Vindication

Despite bans across Europe and the U.S. by the early 1900s, absinthe’s legend never truly faded. Research in the 1990s on old pre-ban bottles disproved the idea that absinthe was dangerously psychoactive, leading to its gradual legalization:

- 1988 – Absinthe was legalized in Europe.

- 2007 – The first authentic absinthes were legally sold in the U.S. after nearly a century.

- Today – Absinthe is once again widely available, though the myths still linger and there is no universal standard for it like there is for Scotch or Champagne.

Absinthe in Cocktails and Cuisine

Beyond the traditional preparation, Absinthe has found a place in modern mixology and culinary experiments:

- Classic cocktails: Sazerac, Corpse Reviver No. 2, Death in the Afternoon, to name a few.

- Culinary uses: Absinthe-laced chocolates, seafood flambé, and even ice cream.

Its intense herbal flavor means a little goes a long way, but for those who appreciate its complexity, absinthe adds an unforgettable twist.

What’s Next for the Green Fairy?

Absinthe is experiencing a renaissance, with craft distilleries producing historically accurate versions and cocktail culture is embracing its bold character. However, it still faces legal inconsistencies and a century of bad press resulting in a lingering and unwarranted stigma that it must recover from.

But after a century of controversy, the Green Fairy is no longer a forbidden spirit: she is out of the bottle—a legend reborn.

Final Toast

So, should you ever find yourself in the company of a bottle of real absinthe, take your time. Let the water drip slowly. Watch as the fairy awakens. And when you take that first sip, remember—you are not simply just having a drink, you are partaking in a historical ritual.

References:

Wittels, Betina J, and Breaux, T.A. (2017). Absinthe: The Exquisite Elixir. Fulcrum Publishing.

N/A. (n.d.). “Death in the Afternoon (cocktail).” Wikipedia. Death in the Afternoon (cocktail)

N/A. (n.d.). “L’Absinthe.” Wikipedia. L’Absinthe

Images:

- · “194+ Different Types of Spoons and Theirs Use with Image.” https://194crafthouse.com/blogs/inspiration/different-types-of-spoons-and-theirs-use-with-image

- “Antique Absinthe Fountain, Pineapple Style.” https://www.maisonabsinthe.com/antique-absinthe-fountain-pineapple-style-43303/

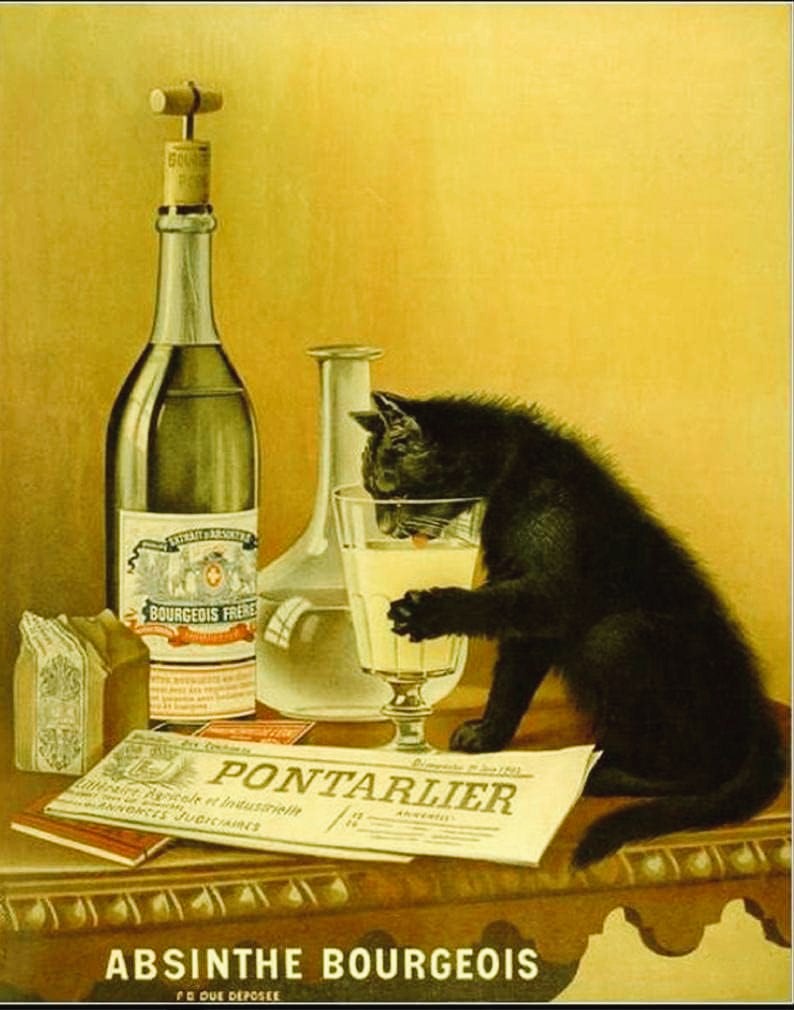

- “Absinthe Bourgeois (1902)” https://a.co/d/3XhP4pZ

- “A fantastical photorealistic image with subtle Art Nouveau undertones, featuring a glass of green absinthe, three tiny, lithe, and green fairies” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Death In the Afternoon Recipe.” https://realabsinthe.blogspot.com/

- “L’Absinthe by Edgar Degas.” Degas https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Absinthe#/media/File:Edgar_Degas_-_In_a_Caf%C3%A9_-_Google_Art_Project_2.jpg

Further Reading:

“Absinthe Museum.” Musée de l’Absinthe. https://lafee.com/musee-de-labsinthe/

Jesse Hicks. (October 5, 2010). “The Devil in a Little Green Bottle: A History of Absinthe.” Science History Institute. https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/the-devil-in-a-little-green-bottle-a-history-of-absinthe/

A wonderful read! I do own a bottle of absinthe and have tasted it. It’s a very beautiful experience. Thank you for this blog and I can’t wait to read the next blog.

Amazing history. The Degas painting really captures something powerful. I’ve never been able to find real absinthe in my life, I’m so curious how expensive it is! Alas, I wouldn’t be able to imbibe as a now teetotaler. But I might gift a bottle.:)