Last week I wrote about Edwardian depictions of women and the threat that many men felt about women claiming more and more independence in the early 1900s. One of the common depictions was of a wife heading out of the house with the husband forced to stay at home and attend to the laundry. This, combined with pretty hot temperatures where I am, got me thinking about how clothing was kept fresh before the washing machine came on the scene. What did the Victorian laundry day look like?

Victorian laundry day: a quickly evolving household task

While people were still doing their wash by hand in the Victorian Era, the process had been very recently refined and had evolved from a lengthy, once in a while chore to a once a week, routine task. This was largely due to two factors. First, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution brought some simple yet game-changing advancements to the washboard. Previously a large, wooden, and cumbersome contraption, it became fixed with lightweight metal boards, making it a portable and ubiquitous household item.

Second, knowledge and concern over proper sanitation entered the public consciousness at a rapid speed. With this new awareness, soap was mass-produced and used. The addition of more soap combined with the new ease the washboard now had made for a much easier wash day, and they occurred more often.

A post about how laundry was done before the 1800s would be entirely different!

But without washing machines, dryers, eclectic irons, and spray-on stain remover, keeping clothing clean looked a lot different during the 1800s. Let’s take a look at some of the more noteworthy aspects.

Victorian laundry day: the process

The person in charge of the household laundry had to make sure that their calendar was cleared for at least an entire day and a half. A strong back and arms were required as well. Though the process varied depending on the household, a typical “load” of laundry would look something like this:

- Soak the laundry overnight in lye or soap. Each piece would need to be individually set and pushed down in the large wooden tub. Any mending would be done at this point.

- The next morning, a large copper pot would be filled with water, along with several buckets of water. The water in the copper pot would be brought to a boil.

- Each piece was removed from the overnight soak and scrubbed using the washboard. Then, each piece would be wrung dry and turned inside out.

- Each piece was then scrubbed a second time.

- The white cotton pieces (all of the underclothing worn directly next to the skin) along with the linen was placed in the boiling water. Any other laundry (there wouldn’t be much) was set aside to be rinsed.

- Using a large, heavy washing bat, the laundry was moved around to get a good boil. Using the same bats, it was then placed through a wringer or wrung by hand before being put into the final rinse. (I keep getting images of Charlie’s mom in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.)

- Each piece was then rinsed with the other water, wrung, rinsed, and wrung a final time.

- Phew! It was now time to head to the laundry lines, shrubs, or whatever else was available for drying. If the weather wasn’t permitting, it was hauled inside for a long day of indoor drying.

A note on the “wringing” process

The wringing of laundry was sometimes done by hand, but more typically with a large and laborious machine called a mangle. This must have been one of the most labor-intensive aspects of the Victorian laundry day.

Not only would it have been difficult to line each piece of clothing one by one to go in, but it was also hard to turn, and the top had to be adjusted depending on the thickness of the item. I can imagine many sore arms for those getting used to it.

What about the big dresses?

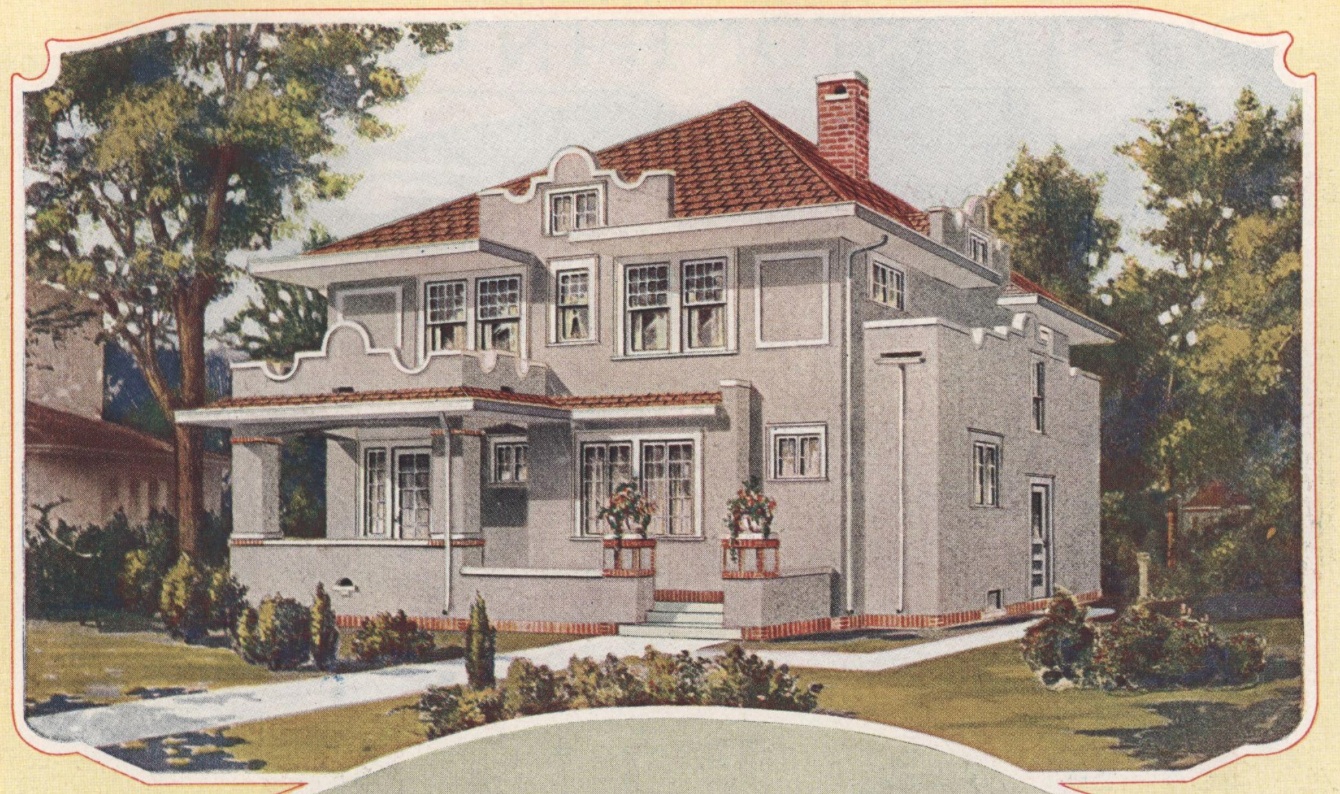

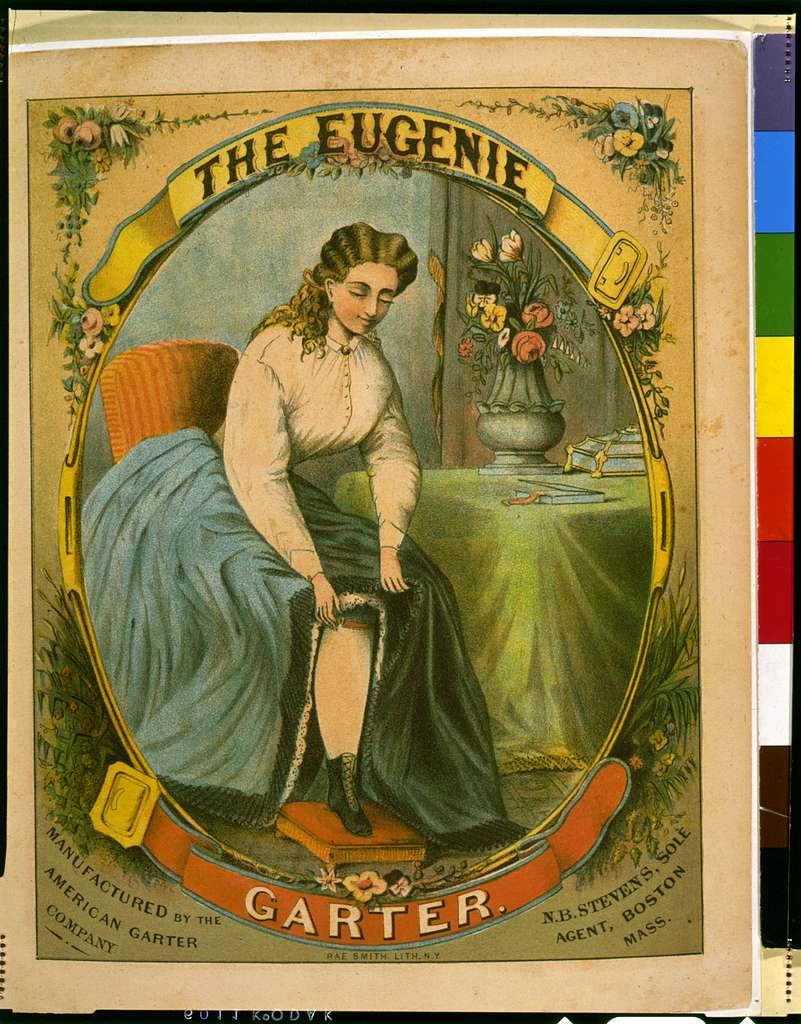

Remember that up until the 1930s (roughly), underclothing was almost always worn. For women, this meant pantaloons, chemise, corset, petticoat, and stockings. While warm, this type of daily wear was practical as it meant the heavier outerwear didn’t need the same washing. Outer clothing would have received a good brushing, some spot treatment, or a scrub without the boiling.

Treating stains

Because clothing was handmade and of higher quality in Victorian times, no matter how wealthy you were, it was important to preserve garments. This meant a variety of treatments for stains. Here are some of the most common and the most surprising.

Ink stains: buttermilk

Blood: Kerosine

Iron /rust: sour milk

Grease stains: Chalk

Grass: Alcohol

Paint on muslin: coat in butter before washing

Paint on silk: Turpentine

Mildew: Soap, salt, starch, one lemon

Wine: Salt, buttermilk, yellow soap

Stains on a mourning dress: figs

Bleaching

As I mentioned above, a large amount of the clothing washed on a typically Victorian laundry day was white cotton undergarments. This meant that a lot of bleaching was necessary. A lot. To bleach, everyday undergarments were boiled in some of the following:

Buttermilk

Lemon water

Onion water

Once washed, wrung, boiled, and wrung again, the clothing would be put in the sun to dry and to receive the bleaching effects of sunlight. When the entire process was complete it would be repeated until the desired whiteness was achieved.

Now, unfortunately, I can’t write about washing laundry in Victorian times without mentioning the use of urine. I came across this little bit of information many times while I was researching this post. Apparently, the natural properties made human urine a commonplace bleaching and disinfecting tool for many years before the full onset of the Industrial Revolution. When I went to collect more information, however, I quickly decided against it. Let’s just say that it may have been utilized and leave it at that.

Preserving color

Victorians took the preservation of their clothing seriously, and this often meant ensuring that the color stayed bright. If a dress, gloves, hat, scarf, petticoat, or handkerchief needed a bit of brightening it would either be given a color treatment or dyed. The dyes used are also the topic for an entirely new post, but I will mention some of the color treatments here.

I have to hand it to them, the domestics of the Victorian era were creative folks!

Colored muslins: wine (a “dessert spoonful to a gallon” according to The Workwoman’s Guide)

Greens: add a half pence to the washing water

Black silk:

-Beer mixed with milk

-A combination of figs, gin, and spirits of wine

-Black tea, washing soda, dissolved gum arabic

-Coffee

Ironing

A lot of what I’ve read about doing laundry in Victorian times suggested that it was the ironing that caused the real angst with domestic workers and homemakers. That is probably because it was done using a cast iron flat iron, also known as a “sad iron.” Why sad? The thing weighed between five and nine pounds. You have likely seen various models if you have spent much time in vintage or antique shops. Next time you do, pick it up and imagine ironing piles of laundry with it!

Laundry doesn’t sound so bad now, does it?

Laundry is one of the most hated household chores in America, ranking in at #2 after washing the dishes. I find this surprising as it doesn’t phase me one bit. Then again, I’m the type of person who cleans for fun, so I guess that’s not a surprise. But if laundry is the second most hated chore that means that many of you reading dread the thought of the clothing piling up in your laundry basket. If this is you, how do you feel about it after reading the lengths that Victorians had to go through to get everything clean?

Thank you for reading, Hope! It certainly is easy, and much easier on the body than it was back then! Those woman must have had pretty toned arms!

Wow! I will think of how easy my laundry ? day is now.

Don’t forget using dew on the grass- leaving the garment/item out to receive treatment.

It was the combination of the actions of the lawn/green grass and the dew forming.

Thank you for the above information, this article was informative, makes me wonder what I can use around the house in a pinch….