One of the more delightful rituals Victorians practiced was the art of making social calls. In a time when the telephone was not in common use, social calls were a way to keep in touch, especially if one was interested in climbing the social ladder. An integral part of visiting was the use of the calling card, a practice that started in Europe and then quickly spread to England and America.

One of the more delightful rituals Victorians practiced was the art of making social calls. In a time when the telephone was not in common use, social calls were a way to keep in touch, especially if one was interested in climbing the social ladder. An integral part of visiting was the use of the calling card, a practice that started in Europe and then quickly spread to England and America.

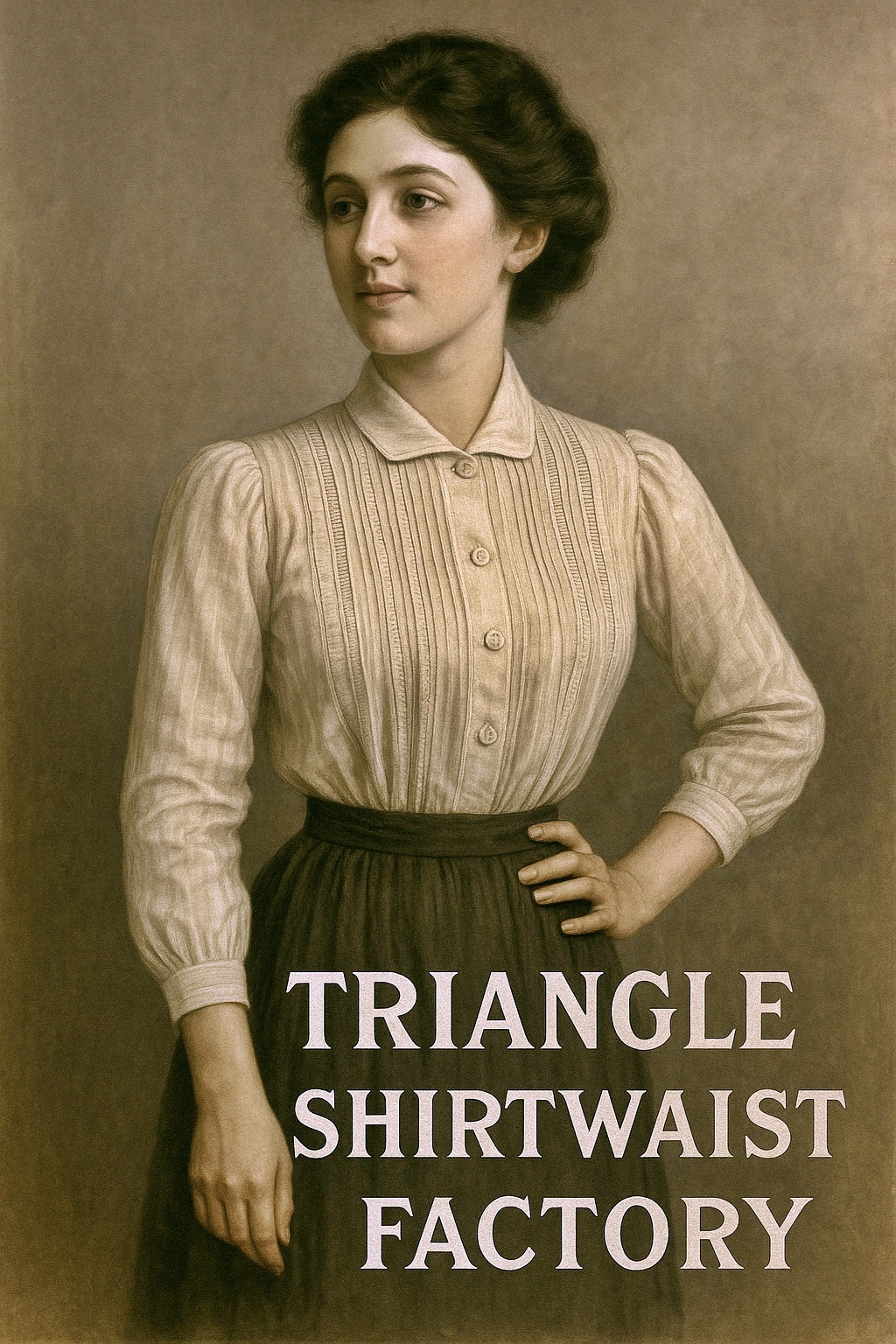

Every lady and gentleman who could afford it carried calling cards. Everything about the card had significance, including the design, motifs and type of paper used.  In general a gentleman’s cards were smaller than those carried by a lady, as they had to fit into the breast pocket of his coat. In addition, men’s cards were on plain paper while a lady’s card might be printed in color on glazed paper. Her card might also be elaborately pierced, or have fringe, lace or other decorative edge. Lady’s cards were often carried in a small case, which could be made of a variety of materials, including ivory and silver. While many cards were printed in black and white and were colored by hand, chromolithography was also popular for producing richly detailed and colored cards. Even children had cards, which were smaller than their parent’s cards, and children would practice exchanging them in imitation of the adults. Some cards were “hidden”, meaning that the actual name of the

In general a gentleman’s cards were smaller than those carried by a lady, as they had to fit into the breast pocket of his coat. In addition, men’s cards were on plain paper while a lady’s card might be printed in color on glazed paper. Her card might also be elaborately pierced, or have fringe, lace or other decorative edge. Lady’s cards were often carried in a small case, which could be made of a variety of materials, including ivory and silver. While many cards were printed in black and white and were colored by hand, chromolithography was also popular for producing richly detailed and colored cards. Even children had cards, which were smaller than their parent’s cards, and children would practice exchanging them in imitation of the adults. Some cards were “hidden”, meaning that the actual name of the  sender would be hidden behind a small picture or verse, which had to be lifted to reveal the sender. There were even double-hidden cards, which might have a picture covering a verse, which in turn covered the name. A black border on a calling card indicated that the sender was in mourning.

sender would be hidden behind a small picture or verse, which had to be lifted to reveal the sender. There were even double-hidden cards, which might have a picture covering a verse, which in turn covered the name. A black border on a calling card indicated that the sender was in mourning.

A message could be conveyed without writing on the card by folding down one corner. If the top left corner of the card was bent or torn, it indicated a social call. A top right corner bent down indicated a visit of congratulations or other good news. If the sender was leaving town, the lower left corner was bent. A visit of condolence was indicated by a bent bottom right corner. If the card was not folded at all, this was an indication that a servant had delivered the card, as a servant would never alter a card. (Author’s note: I have come across  conflicting information about which corner indicated which message, but have provided information here from what I hope to be the most reliable source) Sometimes these corner messages would be printed in French on the reverse corners of the cards; Visite, Felicitation, Affaires, and Adieu, so that the message would be revealed when the corner was folded down. Other than the above-mentioned messages, it was considered bad form to write on a calling card. For example, writing “accepts” or “regrets” in response to an invitation was frowned upon, as an invitation always required a formal note in response.

conflicting information about which corner indicated which message, but have provided information here from what I hope to be the most reliable source) Sometimes these corner messages would be printed in French on the reverse corners of the cards; Visite, Felicitation, Affaires, and Adieu, so that the message would be revealed when the corner was folded down. Other than the above-mentioned messages, it was considered bad form to write on a calling card. For example, writing “accepts” or “regrets” in response to an invitation was frowned upon, as an invitation always required a formal note in response.

Today we exchange business cards, which usually carry far more information than just our names. These cards are meant to be referred to later so that people will have our address, phone number, or know something about our business. Victorian calling cards usually had only the sender’s name, and were a record of who had made a visit, although a gentleman would sometimes add his address to the card. A lady’s card never carried any information other than her name. Depending on the current trend, a middle initial might be used or left out.

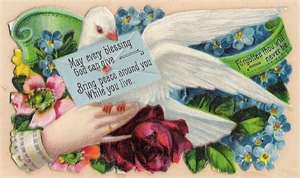

The images and symbols which appeared on the cards had significance to the Victorian. A dove might symbolize purity and devotion, and an owl suggested  wisdom. An image of a swan indicated purity and grace, while a swallow indicated a child or motherhood. Ivy was a sign of immortality and everlasting life, and forget-me-nots were used to symbolize affection. Violets were a sign of shy modesty and quiet virtue. Hands were also a popular motif, symbolizing friendship when clasped, or holding a rose to symbolize love. A hand holding a fan symbolized flirtation.

wisdom. An image of a swan indicated purity and grace, while a swallow indicated a child or motherhood. Ivy was a sign of immortality and everlasting life, and forget-me-nots were used to symbolize affection. Violets were a sign of shy modesty and quiet virtue. Hands were also a popular motif, symbolizing friendship when clasped, or holding a rose to symbolize love. A hand holding a fan symbolized flirtation.

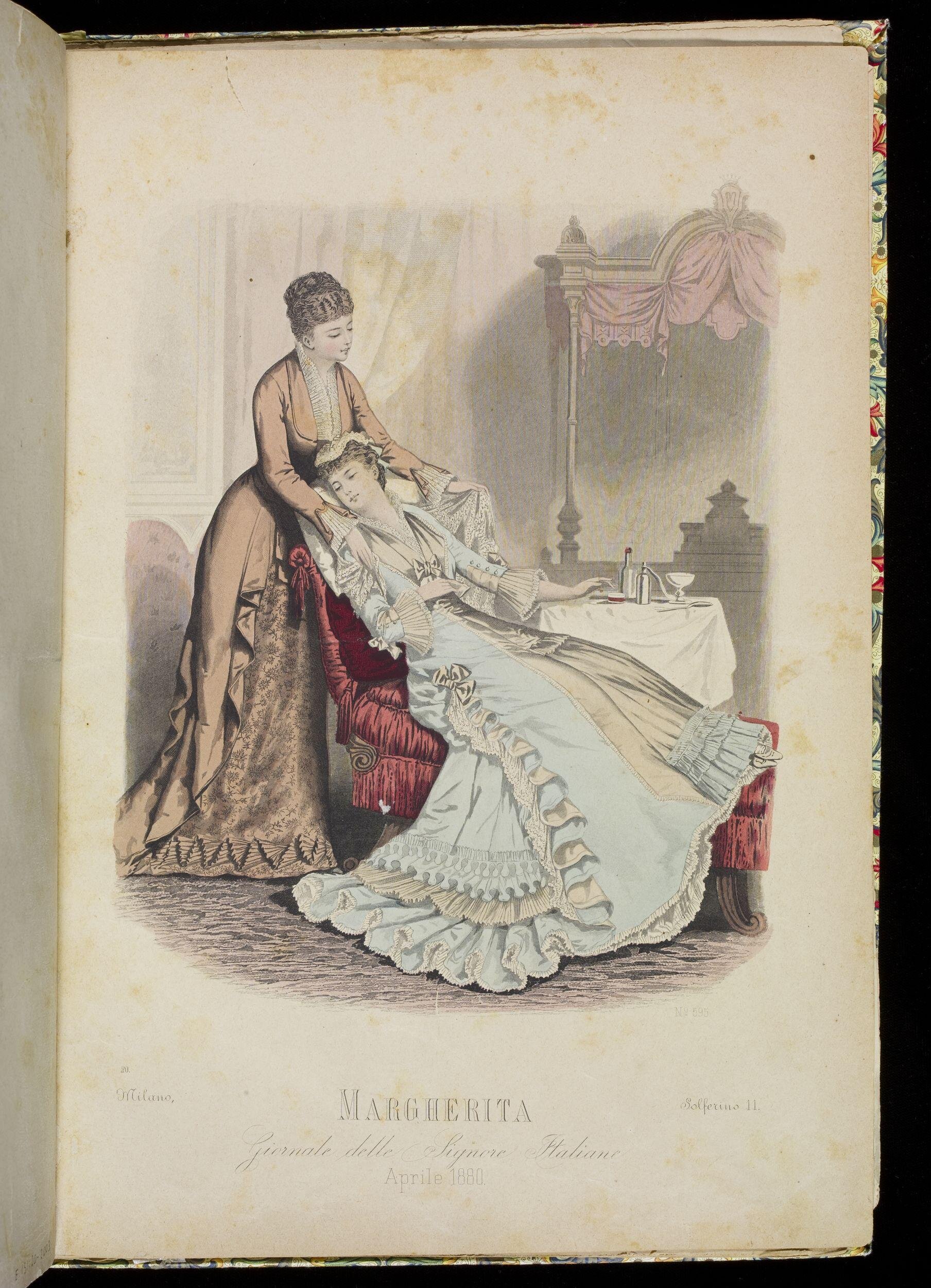

Usually when calling, the visitor would give his or her card to a servant who would then take the card to the lady of the house. She would see the card and  then decide if she would receive the caller. If no one was at home, the card would be left in the foyer of the house in a special tray placed there to hold calling cards. Visits had specific times. Ceremonial visits – for example in response to a ball, tea or other entertainment – would be made the following day between three and four o’clock. In this instance, it was not necessary to see the host or hostess, but simply to leave a card as a “thank you” for the invitation to the event. Semi ceremonial calls – say for a dinner party – were made between four and five o’clock a day or two after the event. After the passing of a loved one, Mourning calls were made in the afternoon. Calls were never made on Sundays, which were reserved for close friends and relatives. Visits were always kept short, usually less than 30 minutes. If another caller came while one was visiting, it was courteous to leave within a few minutes of their arrival.

then decide if she would receive the caller. If no one was at home, the card would be left in the foyer of the house in a special tray placed there to hold calling cards. Visits had specific times. Ceremonial visits – for example in response to a ball, tea or other entertainment – would be made the following day between three and four o’clock. In this instance, it was not necessary to see the host or hostess, but simply to leave a card as a “thank you” for the invitation to the event. Semi ceremonial calls – say for a dinner party – were made between four and five o’clock a day or two after the event. After the passing of a loved one, Mourning calls were made in the afternoon. Calls were never made on Sundays, which were reserved for close friends and relatives. Visits were always kept short, usually less than 30 minutes. If another caller came while one was visiting, it was courteous to leave within a few minutes of their arrival.

By the turn of the century, the habit of using calling cards fell out of favor, though they may still be found in antique shops. The internet also has lovely examples of original calling cards, and some sites even offer designs which may be downloaded and used to create your own calling card. If you are a re-enactor who dresses in period attire (or even if you are simply a romantic at heart) wouldn’t it be just the thing to have your own calling card to exchange with friends or a new acquaintance? What a lovely touch!

Leave A Comment