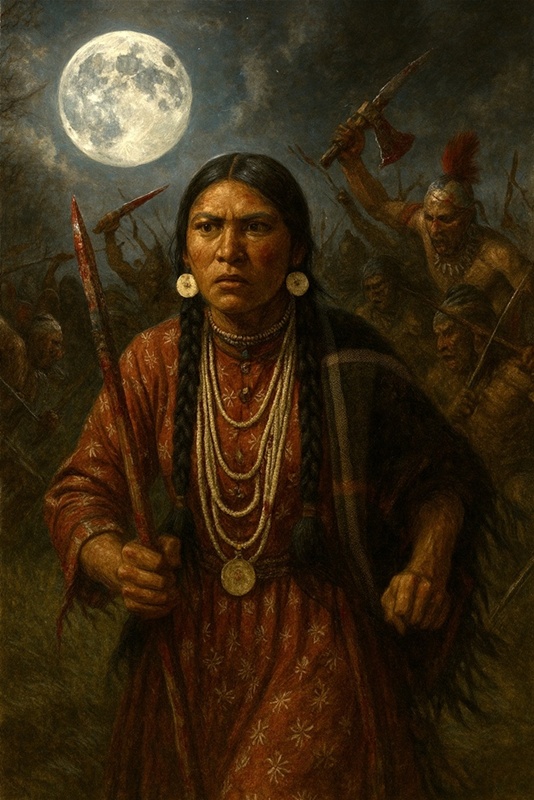

The Truth in Their Names:

Pocahontas, Nancy Ward, and Sacagawea

Author: Christine Skirbunt

Every November, Native American Heritage Month invites us to remember the first peoples of this continent, not only as historical footnotes, but as full human beings whose lives shaped American history. Yet many of us still hold on to incomplete versions of their stories. They are names we know from textbooks or films, but not the truth.

So let us turn to the real stories of three Indigenous women: Pocahontas, Nancy Ward, and Sacagawea, to see them not as side characters in someone else’s story, but as leaders, diplomats, and mothers who navigated moments of intense upheaval. Their legacies endure through the land, through their descendants, and through a growing movement to return their names, voices, and even stolen artifacts to Native hands.

Pocahontas (c. 1596–1617)

Powhatan (Pamunkey), Mediator and Captive Bride

Few names are as misused in American history as “Pocahontas.” Popularized by myth, cartoon, and colonial retelling, she’s often portrayed as a romantic figure who saved John Smith’s life and helped “civilize” Native people. But the real Pocahontas was not a love story. She was a teenager caught in the violent collision of empires and used diplomacy and adaptability to protect her people.

Born around 1596 to Wahunsenacawh (often called “Powhatan”), Pocahontas’s real name was “Amonute,” and she was known privately as “Matoaka.” “Pocahontas” was a nickname, loosely meaning “playful one.” She was part of a powerful confederacy in the Tidewater region of what is now Virginia. According to John Smith, Pocahontas intervened to save his life in 1607, but most historians agree the dramatic rescue was likely a misinterpreted adoption or ritual performance, not the literal event which Smith used to regain the favor he had lost with the London Company.

In 1613, Pocahontas was kidnapped by the English during escalating conflict with the confederacy. During her year-long captivity in Henricus, she converted to Christianity, took the name Rebecca, and eventually married John Rolfe. That union is often cited as the first “interracial” marriage in British North America. In an ironic twist, the English Court was aghast Rolfe had married Pocahontas – not because she was a Native but because they felt he overstepped his reach by being a mere commoner who married what the English considered a Princess and therefore above his station.

But the marriage must be understood in context: as a captive in a foreign world, Pocahontas had little control over her fate. For two years she lived at Varina Farms, across the James River from Henricus, with Rolfe and their son, Thomas, who was born in January 1615. By 1616, she travelled to England with Rolfe and was paraded through England as “proof” that Native people could be “tamed.” She was, by accounts of the time, seen as the linchpin in making sure the Natives could be converted to Christianity. She was a pawn who, while mastering the art of survival, died the following year, in 1617, around the age of 21. She was buried in England but her exact burial spot has been lost to time.

Her story, for centuries, has been romanticized and flattened into a fantasy of cooperation and assimilation. But today, her descendants and the Pamunkey Nation are working to reclaim her truth, correct the myths, and resist how her name has been commodified.

Nancy Ward (c. 1738–1822)

Cherokee, Ghigau (“Beloved Woman”), Diplomat, and Peacemaker

Nanyehi, known to English settlers as “Nancy Ward,” was born around 1738 in present-day Tennessee. She came of age in a matrilineal Cherokee society, where clan mothers and women held significant political power. Nanyehi herself earned the title of Ghigau, or “Beloved Woman”. It was the highest honor a Cherokee woman could receive and with it came the power to speak in council, pardon prisoners, and lead in times of war and peace.

She gained this recognition for her part in the 1755 Battle of Taliwa. Nanyehi fought alongside her husband against the Cherokee’s traditional enemy, the Muscogee (Creek) people. After her husband, Kingfisher, was killed in the battle, Nanyehi picked up his rifle and led the Cherokee warriors to victory. For her courage, she was made “Beloved Woman.” This made her the only voting woman member of the Cherokee general council. She was authorized to become an ambassador and negotiator for all her people.

In doing this, Nanyehi became a genuine ambassador between the Cherokee and the British and European Americans. When Nanyehi met with American delegations, she expressed surprise that there were no women negotiators among the Americans. She used her unique role for decades as a diplomatic bridge between the Cherokee and the young United States.

In the late 1750s, Nanyehi married Irish trader Bryant Ward. She then became known as “Nancy,” the anglicized version of her name. Nanyehi advocated for peace and cooperation, signing treaties and warning both her people and American settlers about the risks of escalating violence. She kept her people fed during famines after being taught the art of dairy cow husbandry and, late in life, she operated an inn that welcomed Native and non-Native travelers alike in Southeastern Tennessee.

Yet, like many Indigenous leaders who sought peace, her efforts were met with betrayal. Despite her warnings, the U.S. government repeatedly broke treaties. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed eight years after her death, resulted in the forced relocation of the Cherokee and other tribes in the infamous Trail of Tears.

Still, Ward’s descendants include notable Cherokee leaders, and her story is preserved at the Nancy Ward Gravesite and Memorial in Benton, Tennessee. Every year, Cherokee citizens and allies gather in her memory.

In recent years, Cherokee citizens have also pushed back on the display of sacred items associated with Ward and other historical figures. They are calling for better consultation and repatriation of artifacts housed in non-Native museums. These efforts echo a broader movement under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), urging institutions to return human remains and cultural items taken without consent.

Sacagawea (c. 1788–c. 1812?)

Lemhi Shoshone, Interpreter and Guide on the Lewis & Clark Expedition

No figure from early American exploration is more iconic – or more misunderstood – than Sacagawea. Her image has appeared on coins, stamps, and monuments. But her real story is one of resilience in a life shaped by kidnapping, forced marriage, and survival on the edge of an expanding empire. And despite all these known facts, in actuality, very little reliable information is known about the real Sacagawea – from conflicting accounts about her tribal origins to which decade and where she actually died.

Most contemporary history maintains Sacagawea was born around 1788 into the Lemhi Shoshone in present-day Idaho and kidnapped by the Hidatsa. But some account reverse this and maintain she was from the Hidatsa and kidnapped by the Shoshone. The general agreement is that around age 12, she was kidnapped and later sold or traded into a forced marriage with Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the Upper Missouri in 1804, Charbonneau was hired as an interpreter and Sacagawea joined them. She was pregnant and barely 16.

Her contributions to the expedition were profound. She helped secure horses and safe passage through Shoshone territory by acting as a cultural broker, and at one emotional encounter, reuniting unexpectedly with her brother. Her presence as a young mother carrying an infant, Jean-Baptiste, also signaled peace to the wary tribes they encountered. She translated, interpreted, gathered food, and helped navigate terrain the men of the Corps of Discovery didn’t understand.

Yet despite all she endured and contributed, Sacagawea’s voice is mostly missing from the expedition’s journals. Her name (spelled in many ways, often “Sacajawea” or “Sakakawea”) is still debated. Most scholars agree on “Sacagawea,” from the Hidatsa tsa-ka-ka-wi-a, meaning “Bird Woman.”

Her death is also disputed. Historical sources maintain she died in 1812 of illness; others, supported by oral histories, claim she lived until possibly 1884 among the Comanche and Shoshone. Either way, her life was marked by survival in a world not of her choosing and her image has too often been co-opted.

She’s celebrated as a guide but rarely acknowledged as a girl taken from her home, married to an older man, and written over by white male chroniclers.

In recent decades, Native communities have pushed back on the romantic statues of Sacagawea, especially those that show her trailing behind Lewis and Clark. A prominent statue in Charlottesville, Virginia, was removed in 2021 after criticism from Indigenous activists and scholars who argued that she deserved a position of dignity and agency, not subservience.

A Shared Legacy and a Call to Listen Closer

What binds these three women – Pocahontas, Nancy Ward, and Sacagawea – is not only the weight of their names, but the silence that too often surrounds their full stories. Each moved between cultures under extraordinary pressure. Each was written into white historical narratives in ways that served national myths, not Native truth. And each is now being reclaimed, not only by descendants, but by museums, educators, and readers who want to know what really happened.

That reclamation includes more than their true names. It includes:

- Repatriation of artifacts and cultural belongings to Native nations.

- Corrective interpretation at historic sites.

- Representation led by Native voices in textbooks, media, and museums.

- Respectful public art, where Native women are shown as they lived and not romanticized or sidelined.

For Recollections readers who love history and heritage, there is so much we can do. We can start by saying their real names: Matoaka, Nanyehi, Sacagawea. We can ask what’s missing from the stories we were taught. And we can model respectful curiosity: not collecting stories like souvenirs but honoring them as lived lives.

This Native American Heritage Month, let’s remember that these strong women were not symbols. They were daughters, mothers, leaders, and survivors. They walked, paddled, and negotiated through worlds that tried to diminish them. But they are not gone. They are still here: in the land, in the language, and in the truth, which still waits for us to listen.

Leave A Comment