Author: Christine Skirbunt

When we think of fashion’s dangers, we might imagine high heels that twist ankles or corsets that pinch waists. But for much of history, clothing didn’t just cause discomfort – it could kill. From flammable fabrics that turned stages into infernos to toxic trades that poisoned entire industries of workers, fashion has left behind a trail of tragedy.

As we near Halloween, we open the doors to haunted wardrobes and peer inside three eerie “cabinets,” each filled with garments and textiles that carried hidden dangers. These clothes may have once signified elegance, innovation, or even safety, but behind their beauty lurked a deadly cost.

Wardrobe One: Toxic Trades

Fashion’s pursuit of beauty has often come at the expense of workers’ lives. Long before fast fashion, entire trades were haunted by the chemicals and processes required to create sought-after fabrics and accessories.

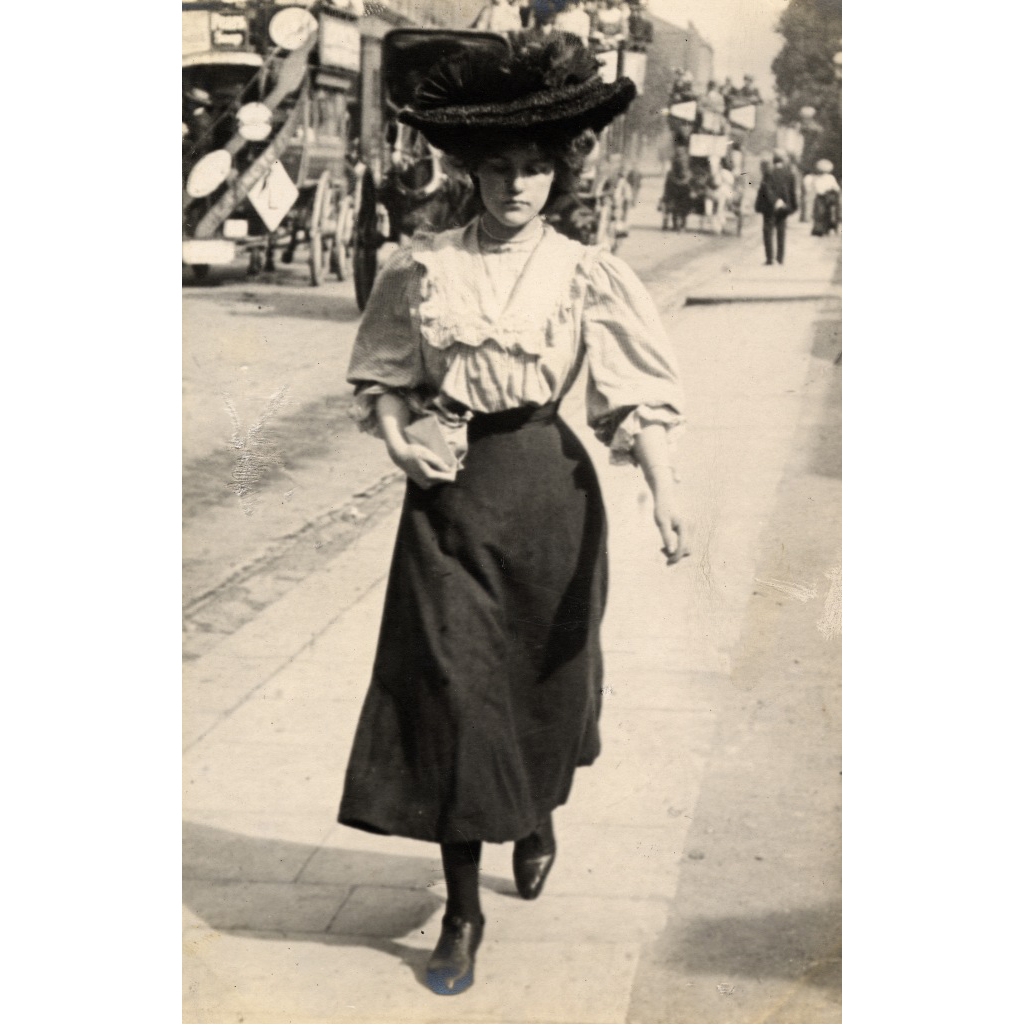

The Mad Hatter’s Curse: Felt Hats

From the 17th through the 19th centuries, no gentleman was complete without a felt hat as it was considered “socially unacceptable for European men to leave the house hatless.” (McMahon, David: 8) But the fur used on these hats was hard to work with and time-consuming. That is, until the 1730s, when hat makers discovered if they added mercury to the mix, pelts became much easier to create into felt. Animal pelts were processed into soft felt using mercury nitrate, a chemical that smoothed fibers and gave hats their crisp, stylish finish.

The cost? Negligible to wearers as the hats were coated in shellac and lined with silk and leather. But the workers inhaled mercury vapors daily as they steamed and shaped felt. The results were devastating: trembling, blackened gums, slurred speech, memory loss, and paranoia (to name just a few symptoms). Some workers even smelled of metal. Their conditions became so notorious it was nicknamed “The Hatter’s Shakes” or “Mad Hatter Disease.”

As early as 1757, French doctor Jacques-Rene Tenon observed that most hatters didn’t live past fifty and were ill years before their deaths. His findings were ignored and mercury’s toll lingered well into the 20th century. Shockingly, it wasn’t banned from hat-making. It wasn’t until after nearly three centuries of occupational deaths and madness that it was the declining popularity in hats which ended the usage of mercury to make felt.

Poison in the Air: Viscose Rayon

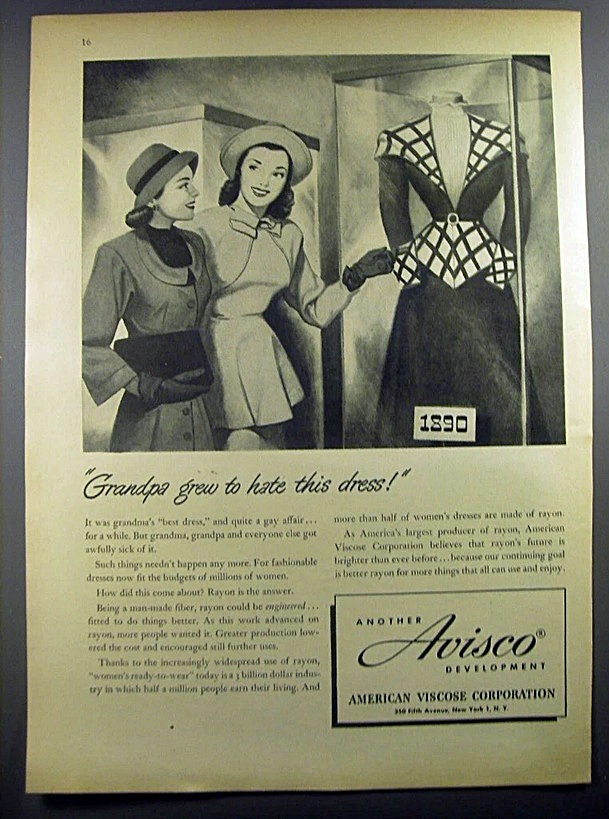

In the late 19th century, viscose rayon was hailed as a miracle fabric. It was invented in 1891 and was considered a glamorous, budget-friendly alternative to real silk. By the 1910s and 1920s, rayon was seemingly everywhere: from stockings and dresses to even furniture upholstery.

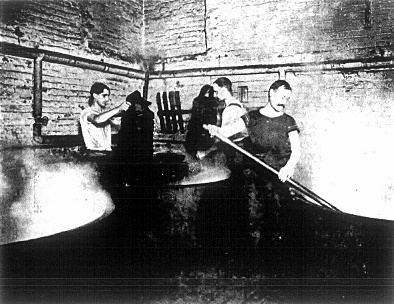

But in the factories a different story was playing out and workers were paying with their lives. The viscose process relied on carbon disulfide, a solvent so toxic it damaged the nervous system. Men and women who spun rayon fibers often developed neurological damage, tremors, hallucinations, violent mood swings, and early death.

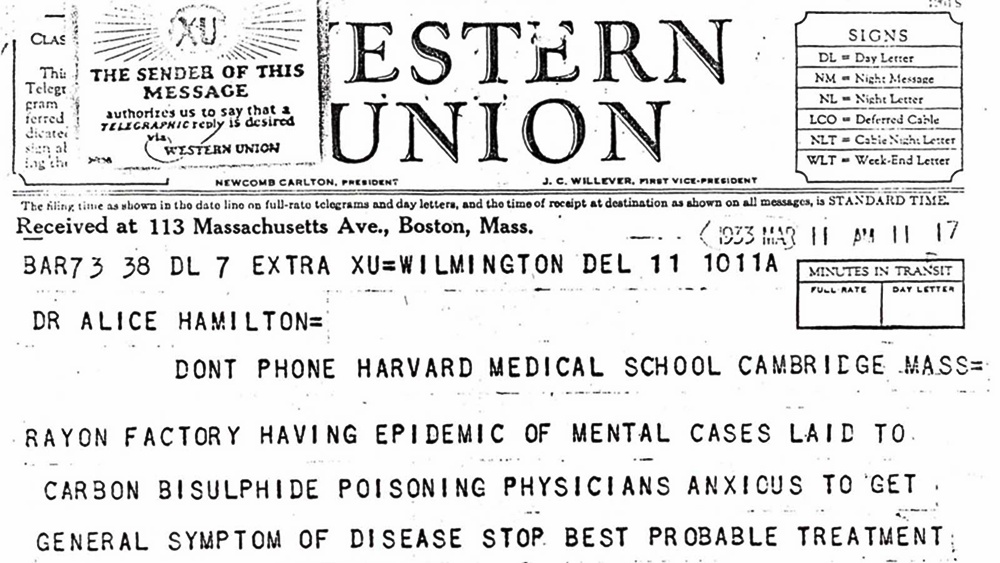

Recognized by doctors in the early 1900s, it was called “Rayon Worker’s Disease.” In 1933, the US Public Health Service investigated rayon factories and confirmed widespread illness linked to production. Yet companies covered-up the dangers, prioritizing profit over safety.

Because the finished garments were safe to wear, the manufacturing process left behind poisoned workers that few consumers knew (or cared) about:

“Which is why it’s gone on so long. Because when consumers aren’t affected, there’s not very much impetus for outrage if it’s just the poor people making it that suffer.” (Why Rayon is Killing Industry Workers: author Paul Blanc)

Today, in developed countries, there are now stricter industrial safety standards. US and European factories are more regulated, but in places like Asia, however, workers are still being exposed.

The Fireproof Death Trap: Asbestos In Everything!

Not all dangerous cloth was meant for fashion. Some were designed to save lives – but ended up stealing them instead.

Known since the ancient Greeks and encountered by Marco Polo in Mongolia in 1280, by the 19th century, asbestos was celebrated as a wonder material. Resistant to fire, it was woven into everything from theater curtains to the 1850s Paris Fire Brigade’s uniform material.

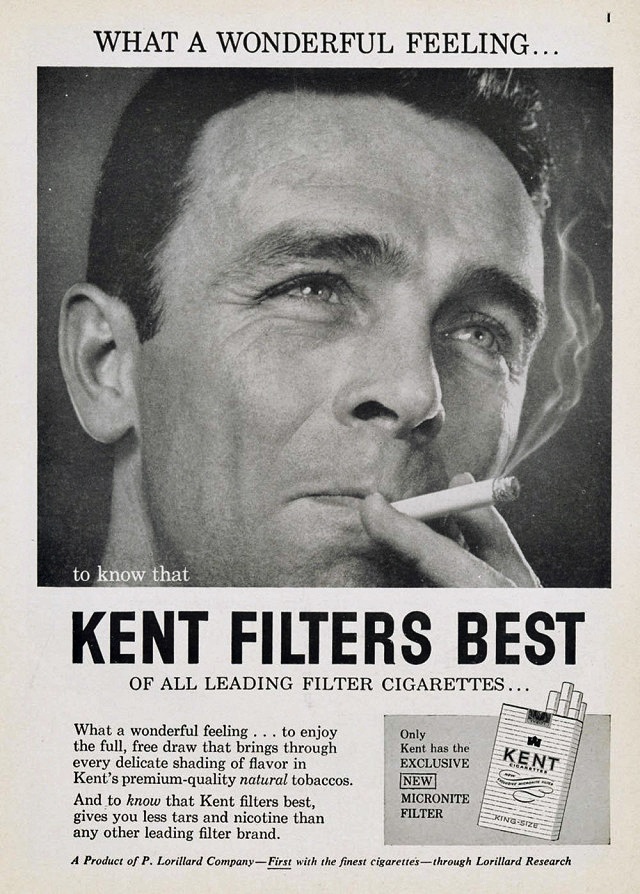

Anything that could be made with asbestos seemingly was – from mattresses to (yikes!) filtered cigarettes! The American cigarette brand, called Kent, was launched in 1952 and claimed to revolutionize the cigarette filter technique. They were produced with asbestos for four years before the company quietly changed the filter material to acetate after internally acknowledging the risk and liability of using asbestos.

Industrial Revolution manufacturers employed men to extract asbestos from the mines while thousands of women and children prepared and spun the raw fibers into cloth. The tragedy lay in its fibers. Asbestos breaks down into microscopic shards that lodge in the lungs. Decades later, wearers and workers alike developed asbestosis, lung cancer, and mesothelioma. The very fabrics meant to shield people from flames condemned them to slow, suffocating deaths.

In 2005, asbestos was banned entirely in the EU. And while its usage has declined significantly, asbestos is still not banned in the US. (The Surprising Ancient Origins of Asbestos)

Wardrobe Two: Flammable Fashions

Now, let’s open another door, for if the first cabinet of our haunted wardrobe was about poisons in clothing, the second is about fire. Across the 19th and early 20th centuries, some of the most fashionable fabrics turned their wearers into human torches.

Ghostly Flames: Tulle Netting

Delicate, airy, and ethereal – tulle became the fabric of dreams in the early 1800s. Invented in 1809 with a machine that could make yards of tulle netting in mere minutes, “the fabric’s simple honeycomb pattern was practically weightless and made dancing look like floating.” (McMahon, David: 42). Brides wore tulle veils down the aisle, not excluding Queen Victoria herself, and ballerinas glided across stages in white, gauzy tutus.

Made from silk, cotton, or later, nylon, beauty came with a cost. Tulle was often stiffened with starch, making it even more flammable than ordinary silk or cotton. And onstage, dancers twirled dangerously close to gas jets and footlights.

In 1862, French ballerina Emma Livry’s tutu caught on a stage light during a rehearsal. Her outfit burst into flames immediately. Less immediate was her death: she lingered for eight months before dying of her burns at just 20 years old. But her fate was far from unique: in 1859 French authorities passed a law requiring all costumes be coated with alum, borax, and boric acid. This prevented fire but made the tulle stiff and dingy. Livry refused to wear treated tutus and she paid dearly for it.

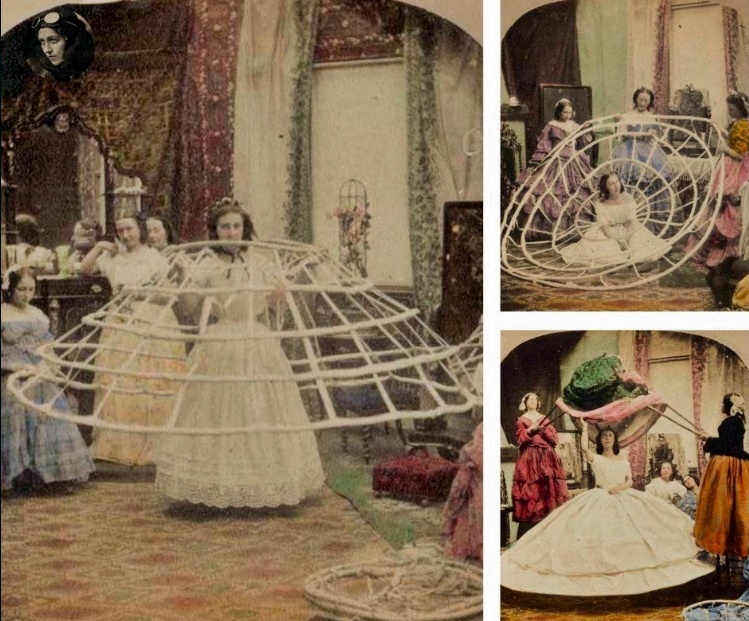

Fire in the Parlor: Crinolines

Few fashions are as visually striking – or as deadly – as the Victorian crinoline. Introduced in the 1850s, early versions used horsehair and linen to achieve the huge bell-shaped skirt. In 1856, the steel-hooped cage crinoline allowed skirts to expand without the weight of layers of petticoats.

The look was extravagant, but it could come at a horrifying price. The unwieldly skirts often brushed against fireplaces, candles, and oil lamps. Once alight, the voluminous fabric burned in seconds, engulfing women from head to toe as the steel frame around them became a cage of fire.

In 1863 alone, The New York Times reported that in a single 12-months span 3,000 women worldwide died from crinoline fires. On average, crinoline fires killed about 300 women a year in England, including author Oscar Wilde’s two half-sisters.

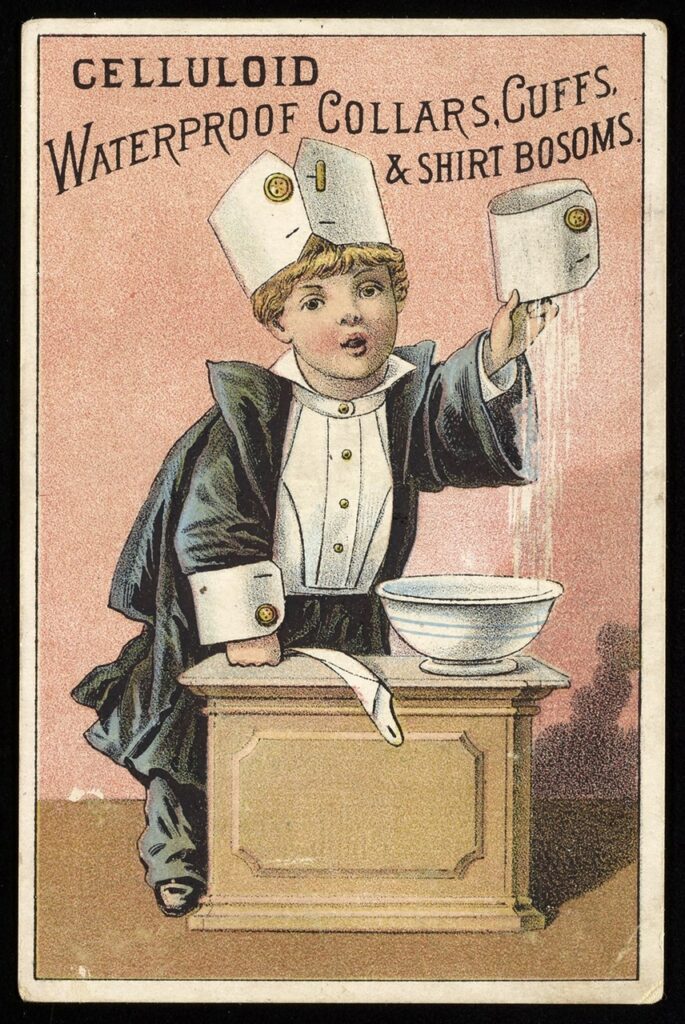

Explosions in the Boudoir: Celluloid Cuffs and Combs

The late 19th century saw the birth of celluloid, the world’s first plastic. Marketed as “The Material of a Thousand Uses” because it was cheap and versatile, able to mimic ivory, tortoiseshell, and horn. Soon, men wore celluloid cuffs and collars, while women adorned their hair with celluloid combs and their wrists with bracelets.

But there was a catch: celluloid was highly explosive. A stray spark from a match, cigarette, or fireplace could ignite it instantly. Sometimes it could self-ignite on a warm day!

Manufacturing was so dangerous because the temperature that makes celluloid soft and moldable is nearly the same as the temperature that could make it burst into flames! The New Jersey Celluloid Manufacturing Company had 39 fires with nine deaths over its 36-year history.

England didn’t fare much better, with England’s largest department store fire in history being the direct result of a festive holiday window display filled with celluloid hair accessories that instantly ignited into a huge fire.

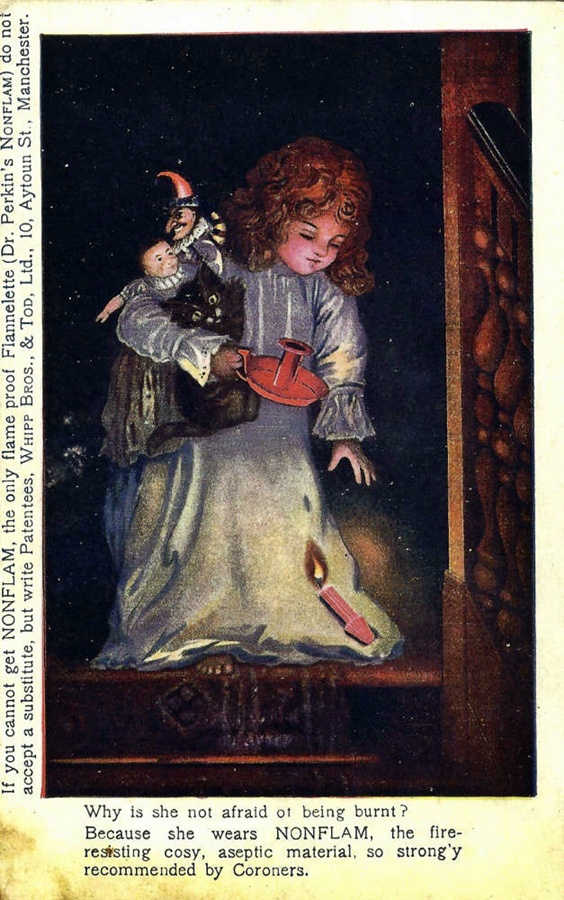

Nightgowns of Fire: Flannelette

Flannel was popular and in demand, but working-class families could not afford it. In 1877, manufacturers discovered if they brushed cotton, it would feel like flannel at a fraction of the cost to make. They dubbed this new creation “Flannelette.”

The problem was that real flannel is tightly woven wool and virtually fireproof, while Flannelette is a soft, fluffy cotton that is highly flammable. In tight living quarters, such as those shared by the working-class, children were often near stoves, candles, or fireplaces. Over a five-year period 1,816 children burned to death while wearing Flannelette in England.

Flannelette factories were one of the few places “where workers were more protected than wearers: the room where the nap was raised was fireproof, and, as an additional precaution, beside each machine is a hose-pipe.” (Cheap flannelette, gender, and the death of children)

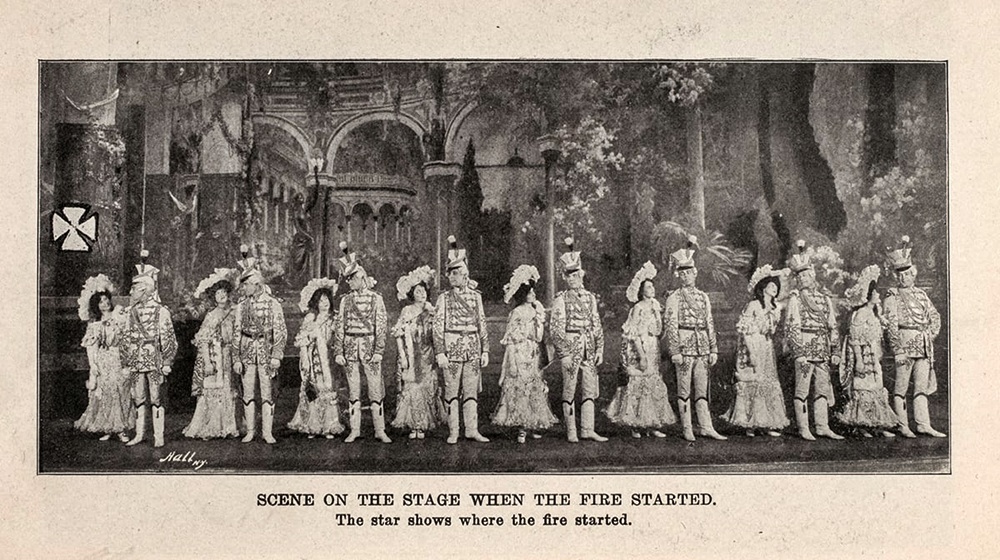

The Inferno of 1903: The Iroquois Theatre Fire

Many of the hazards mentioned in this article reached a nightmarish climax in Chicago on December 30, 1903.

The Iroquois Theatre, proudly advertised as “absolutely fireproof,” and opened for less than a month, was packed that afternoon with almost 1,900 women and children for a holiday matinee. Onstage, dancers twirled in gauzy tulle and muslin costumes beneath blazing gaslights.

During the second act, a stage lamp sparked, and the scenery ignited. Within moments, flames raced across the stage and onto the costumes of chorus girls. Eyewitnesses described ballerinas running in panic, their tulle tutus burning like torches.

The fire curtain, supposedly made with asbestos fibers, failed to drop and then turned out to be flammable! The audience panicked but found most exit doors were locked or unmarked, and iron gates blocked stairways out. The panic turned the crowd into a stampede. By the time it was over, 602 people were dead. It was the worst single-building fire in U.S. history.

The Iroquois Theatre Fire forced reforms: clearly marked and outward-swinging exit doors, mandatory fireproof curtains, and restrictions on flammable fabrics in costumes and scenery. But its legacy remains a chilling reminder of how fragile beauty and safety once were.

Wardrobe Three: Closing the Wardrobe

Today, many of these fabrics and processes are gone – banned, replaced, or better regulated. But the ghosts of fashion past still linger. Every crinoline fire, every poisoned hatter, every factory worker driven to madness is a reminder that clothing has never been a neutral part of history. It has shaped lives…and ended them.

As we dress up for Halloween, it’s worth remembering that some of the most terrifying costumes ever worn weren’t in haunted houses or on a stage, but in the very wardrobes of everyday life.

Fashion, after all, has always been about transformation. But in the haunted wardrobe, the transformation was all too often from life to death.

More on Sinister Fabrics by Recollections: Green with Envy

References:

McMahon, Serah-Marie. (2019). Killer Style. Owlkids Books Inc.

“Poisons Part I: The Mercurial World of Felt.” https://www.famsf.org/stories/poisons-part-i-the-mercurial-world-of-felt

“Why rayon is killing industry workers: author Paul Blanc.” https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-february-9-2017-1.3972476/why-rayon-is-killing-industry-workers-author-paul-blanc-1.3972480

“The Surprising Ancient Origins of Asbestos.” https://www.historyhit.com/inextinguishable-the-history-of-asbestos/

“The Right Chemistry: The incendiary history of flammable fabrics.” https://www.montrealgazette.com/opinion/columnists/article94783.html

“The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever.” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-theater-blaze-killed-hundreds-forever-changed-way-we-approach-fire-safety-180969315/

Images:

- Woman’s hat, ca. 1892 France, Paris Rabbit felt; ostrich feathers; silk satin ribbon; faceted jet buckles: https://www.famsf.org/stories/poisons-part-i-the-mercurial-world-of-felt

- Hat-Makers Dip felt hats into nitrate of mercury solution, 1914: https://unframed.lacma.org/2011/03/07/how-the-hatter-went-mad

- 1947 American Viscose Corporation Ad – Grandpa grew to hate this dress!: https://www.ebay.com/itm/284534060158

- 1933 Telegram to Dr. Hamilton regarding rayon mental cases: https://undark.org/2017/06/09/viscose-rayon-occupational-health/

- Women working at an asbestos mattress factory in the early 1900s: https://www.armco.org.uk/asbestos-survey-news/the-history-of-asbestos/

- Asbestos cigarette filters: https://www.e4ltd.co.uk/blog/2021-08-24-weird-historical-uses-of-asbestos-that-may-shock-you

- Portrait painting of Queen Victoria with her tulle wedding veil: https://tulleboxcorner.wordpress.com/2013/08/11/history-of-tulle/

- Carlotta Brianza in Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theater in 1890: https://pointemagazine.com/tutus/#gsc.tab=0

- Crinoline on fire: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1091391266368573&id=100064931286917&set=a.411648947676145

- Early 20th century evening gown embellished with celluloid sequins: https://talkdeath.com/if-looks-could-kill-the-history-of-death-and-fashion/#jp-carousel-13656

- Celluloid waterproof collars, cuffs, and shirt bosoms advert, circa 1890: https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/6t053h17b/viewer/4m90dw763

- Flannelette No-Flam Advert: https://victorianweb.org/art/costume/david2.html

- Iroquois Theater Performers: https://www.wttw.com/chicago-stories/downtown-disasters/the-tragedy-of-the-iroquois-theater-fire

- The lamp that caused the notorious Iroquois Theater fire: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-theater-blaze-killed-hundreds-forever-changed-way-we-approach-fire-safety-180969315/

- Wardrobe Toxic Trades: https://chatgpt.com/

- Wardrobe Flammable Fashions: https://chatgpt.com/

- Wardrobe Fin?: https://chatgpt.com/

Further Reading:

Wright, Jennifer (2017). Killer Fashion. Andrews McMeel Publishing.

“How the Hatter Went Mad.” https://unframed.lacma.org/2011/03/07/how-the-hatter-went-mad

“Rayon, an Epidemic of Insanity, and the Woman Who Fought to Expose It.” https://undark.org/2017/06/09/viscose-rayon-occupational-health/

“Weird historical uses of asbestos that may shock you.” https://www.e4ltd.co.uk/blog/2021-08-24-weird-historical-uses-of-asbestos-that-may-shock-you

“Fashion History Lesson: The Subversive Power of Tulle.” https://fashionista.com/2018/07/tulle-material-fabric-fashion-history

“If Looks Could Kill: The History of Death and Fashion.” https://talkdeath.com/if-looks-could-kill-the-history-of-death-and-fashion/

“The Tragedy of the Iroquois Theater Fire.” https://www.wttw.com/chicago-stories/downtown-disasters/the-tragedy-of-the-iroquois-theater-fire

Leave A Comment