Author: Christine Skirbunt

Modern men’s fashion is often dismissed as plain or predictable, especially when compared to the kaleidoscopic shifts in women’s clothing every season. But history tells another story – one in which men once used fashion as a form of rebellion, identity, and spectacle. When they entered a room, they were never aiming to “blend in” but to purposely be noticed and seen. They wanted to make a statement that couldn’t be ignored. These men were the Fops, the Macaronis, and the Dandies.

Let’s take a closer look at who these men were, how they differed from each other, and how their fashion legacies still endure today.

Fops, Macaronis, and Dandies

While all three of these terms are tied to fashion-conscious men in history and are often used interchangeably, the distinctions between Fops, Macaronis, and Dandies are important. Each reflects not just a style, but the cultural mood of the time.

| Fop Era (circa 1660s–1720s): Extravagant lace, wigs, and brocade. A love of courtly excess and theatrical self-display.Macaroni Era (circa 1750s–1780s): Outrageous Continental-inspired outfits. Towering wigs, narrow coats, bold makeup.Dandy Era (circa 1790s–1860s): Simplicity reigns thanks to Beau Brummell (more on him later!). Dark wool coats, crisp white linen shirts, immaculate boots, minimal but luxurious details.Late Victorian Dandies (circa 1870s–1890s): Artistic flourishes return with figures like Oscar Wilde – velvet, silk, eccentric accessories, yet still grounded in Brummell’s tailored ideals. |

It is easy to confuse who was who, to which era they belonged, and what separated them. A simple timeline of the key style shifts associated with these figures will help keep things in order:

The Fop

The term “Fop” emerged in the Restoration period of the late 1600s. A Fop was a man excessively concerned with his appearance and manners to the point of absurdity. Foppery was accessible to any man with enough wealth and social ambition, but it was most commonly associated with men of means, whether noble-born or not. His clothing was flamboyant: brocade coats, lace cravats, silk stockings, high-heeled shoes, and elaborately curled wigs. His mannerisms were exaggeratedly effeminate, his speech often flowery.

But Fops were not merely fashion enthusiasts: their existence also reflects a period when courtly manners and flamboyant display were powerful tools of social mobility. However, by many in the lower classes, they were often seen as foolish, vain, and shallow. And while Fops dominated England and Europe, they were rare at this early stage in Colonial America.

The Macaroni

In the mid-1700s, the “Macaronis” arose. The Macaroni was usually an upper-class young man returning from his Grand Tour of Europe, steeped in Continental fashion and culture. He was cosmopolitan to a fault, wearing styles considered outrageously foreign by British standards. And unlike their Fop predecessors, Colonial America did have its fair share of Macaronis.

Macaronis sported high, powdered wigs in shades from white to colors in the pastel spectrum. Their wardrobes were also often in pastel tones like baby pink and powder blue, heightening the visual shock for conservative eyes. They often donned tiny hats atop their coiffures, tight-fitting silk suits, jewel buttons, and had a tendency for excessive use of makeup. Their cane twirling, ornate snuffboxes, mincing walks, and Italian-inspired slang made them ripe targets for satire. The term “Macaroni” itself was used derisively, suggesting these men had overindulged in foreign affectations, much like the then-exotic pasta dish from Italy from which the name originates.

The Macaroni and Their Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was a cultural pilgrimage undertaken by young wealthy British men in the 18th century. Designed to complete their education, it involved months – or years – of travel across France, Italy, and sometimes the broader Continent. Supposedly, it was meant to be about studying classical art, architecture, and the refinement of manners.

In reality, many young men returned as Macaronis: enamored with the extravagance of Italian fashion and European court life. These men adopted a visual language of Continental sophistication which clashed dramatically with the more conservative English sensibility.

Their style was lampooned mercilessly in satirical prints and cartoons. Yet, beneath the ridicule, the Macaroni phenomenon reflected deeper anxieties: fears of foreign influence, changing class dynamics, and the fragility of traditional English masculinity.

American Macaroni Before and After the American Revolution

Across the Atlantic, the influence of British Macaronis trickled into Colonial America. Those wealthy enough sent their sons on the European Grand Tour. For the American colonists who could not afford such a trip, looking to London was their main source for fashion cues. To adopt Macaroni styles was to signify one’s cultural sophistication and connection to England in Colonial America.

Before the American Revolution, American Macaronis appeared in major cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, though on a smaller scale than in Britain. For these colonists, Macaroni fashion was a way to assert elite status in a society still defining its cultural identity.

However, as revolutionary fervor took hold, the image of the Macaroni became a symbol of loyalist elitism to British decadence and rule. Revolutionary patriots mocked Colonial Macaronis as effeminate, frivolous, and out of touch with the rugged, self-reliant ideals of the American frontiersman.

After gaining independence from England, the new American Republic distanced itself from aristocratic displays. Practicality, simplicity, and antiroyalist virtue became fashionable, pushing the flamboyant Macaroni into undesirability. Yet, traces of the Macaroni lived on, most famously in the song “Yankee Doodle.”

The History Behind “Yankee Doodle Dandy”

“Yankee Doodle” began as a British taunt aimed at the Colonial American militia in the Revolutionary War. The British used the term “doodle” to mean simpleton or bumpkin. The infamous line – “stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni” – mocked the Colonials’ supposed ignorance of fashion. The implication was that these Colonial Americans believed merely adding a feather was enough to be fashionable by Macaroni standards.

However, the Colonials embraced the insult, turning “Yankee Doodle” into a song of defiance. By the end of the Revolutionary War, it had been transformed into a patriotic anthem. This act of claiming an insult mirrors how Macaronis and Dandies used fashion to challenge societal expectations. After the American Revolution, Macaronis quickly became relics. They were symbols of a colonial identity that Americans could not shed fast enough. But the Macaroni was soon to be replaced by a more aloof and refined figure: the Dandy.

The Dandy

The Dandy represented a shift from flamboyant showiness to refined elegance. Where Fops and Macaronis were gaudy and conspicuous, Dandies prized simplicity, immaculate tailoring, and an aura of detached superiority.

A true Dandy would never overdress or wear makeup. Instead, he mastered understated perfection – flawlessly starched cravats, precisely cut dark coats, gleaming boots, and an attitude of dry wit. Dandyism was not mere vanity; it was both an artistic philosophy and a social performance, exalting elegance and intelligence as a form of personal rebellion.

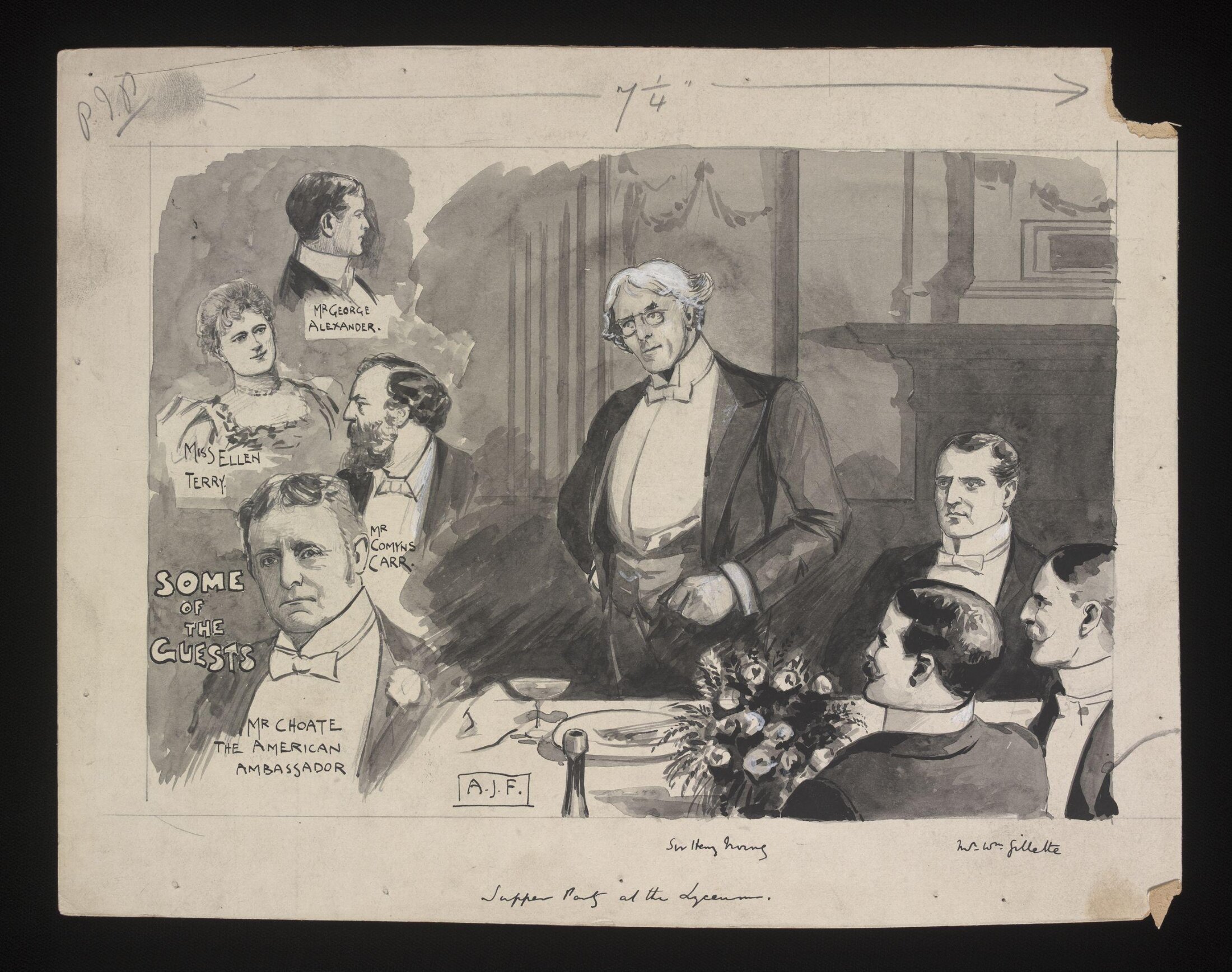

The Dandy Who Defined Modern Menswear

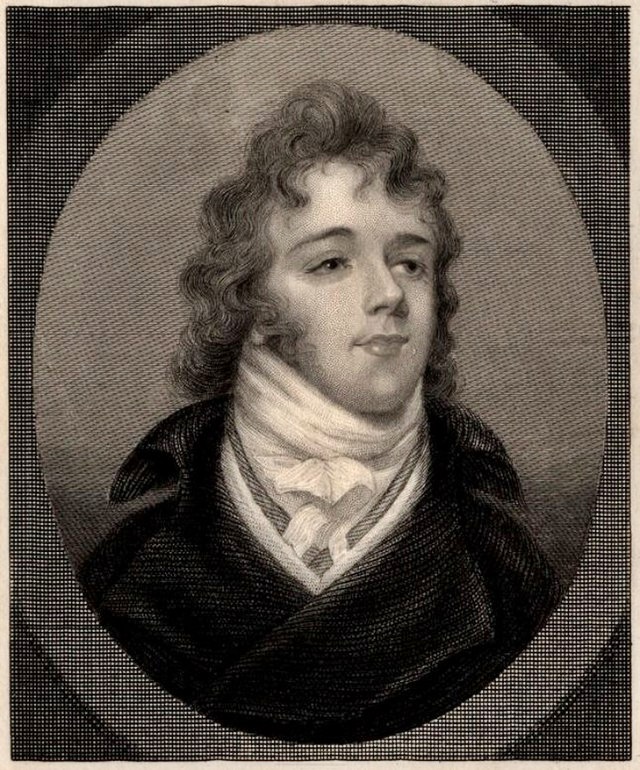

No discussion on Dandies is complete without mention of George Bryan “Beau” Brummell (1778–1840). Considered the original Dandy, Brummel was born to a middle-class family in London. Lacking money, titles, and land, he still ascended to the upper ranks of London society through sheer charm, wit, and his revolutionary style.

Educated at Eton and briefly attending Oxford, Brummell eventually gained favor with the Prince Regent (later King George IV), which catapulted him into the most elite circles. Unlike the Macaroni, Brummell rejected flamboyance in favor of tailored simplicity. He introduced:

- Dark, impeccably fitted coats.

- Crisp, white shirts with high collars.

- Perfectly tied cravats (which reportedly sometimes took Brummell hours to get “just right”).

- Breeches and polished Hessian boot (gone were the high heels of the Fops and Macaronis).

His daily routine of bathing and meticulous grooming was radical in an era when hygiene was lax. Brummell’s understated elegance set a new standard.

Brummell’s Legacy

Though he eventually fell from royal favor in the 1810s – a victim of his own sardonic wit at the Prince Regent’s expense – and died in exile and poverty in France, Brummell’s influence on men’s fashion was, and still is, profound. He is often credited as the father of the modern three-piece suit of today and the prototype for the contemporary gentleman. His name remains synonymous with tailored excellence. He influenced society not by birthright but by style and personality.

Lord Byron, Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde

And while Brummell set the template for men’s fashion and humor, others would elevate Dandyism into intellectual and artistic realms. Men such as:

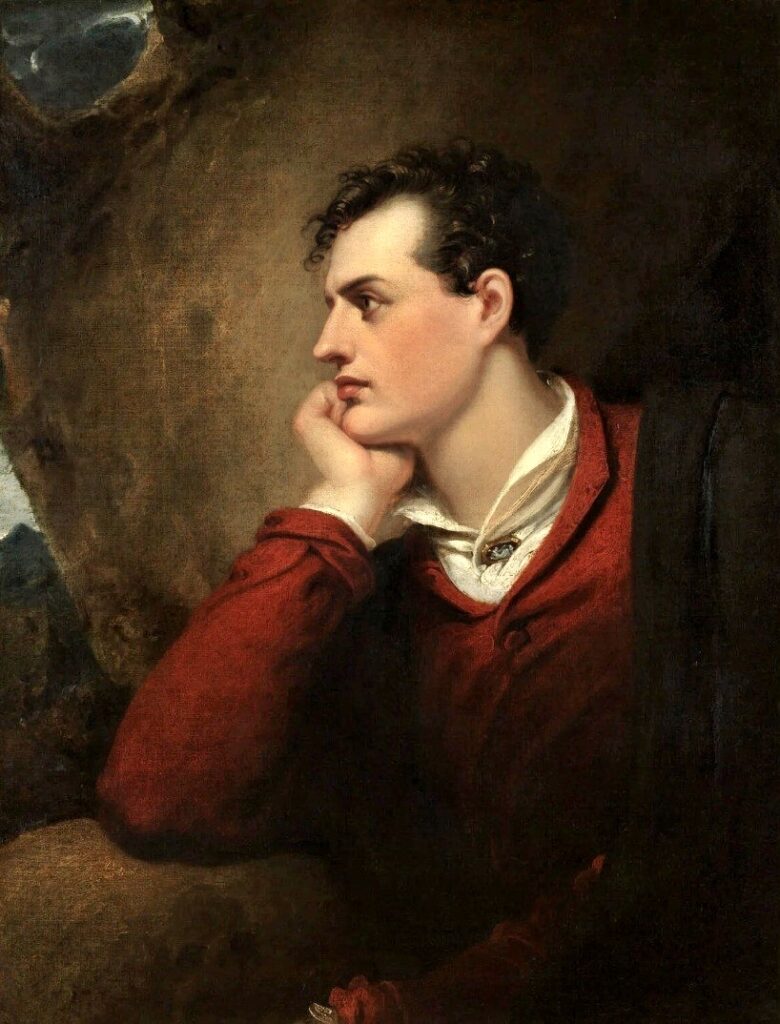

- Lord Byron (1788–1824): Though not always classified as a Dandy, Byron’s carefully cultivated image of the tormented, romantic antihero fits squarely within Dandyism’s tradition. His scandalous personal life and hero persona reflected an early form of celebrity culture.

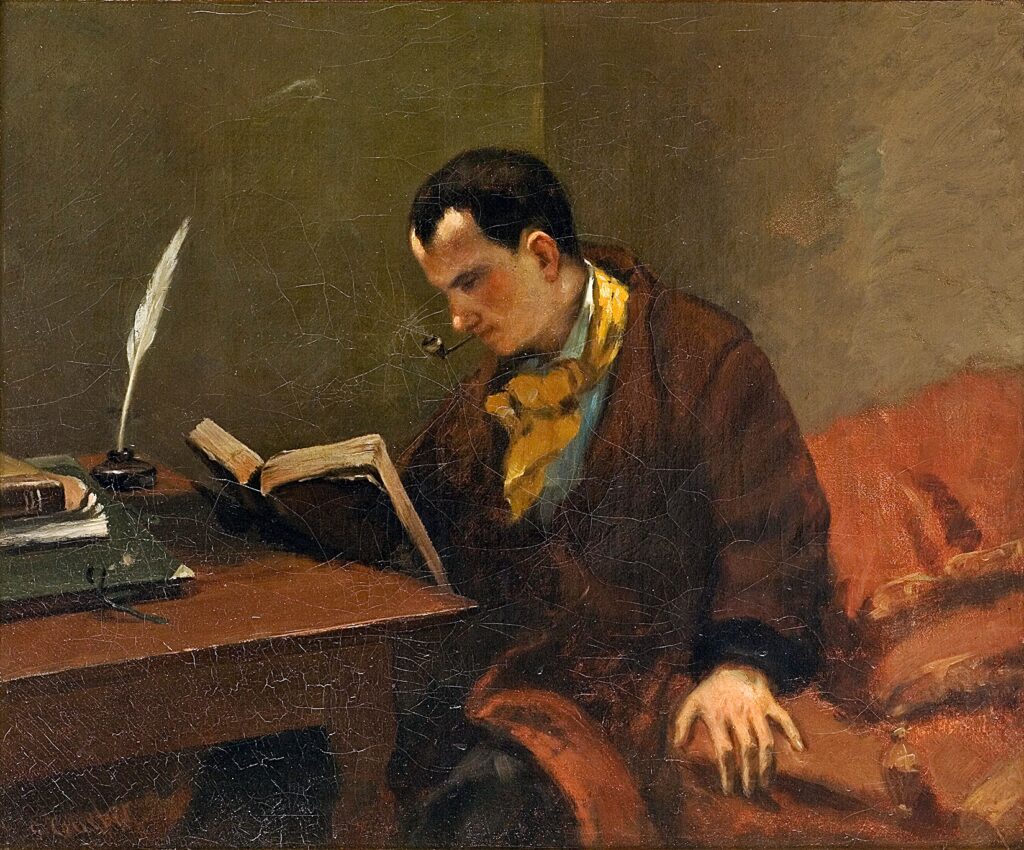

- Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867): The French poet and critic gave Dandyism a philosophical dimension. For Baudelaire, the Dandy was an artist of life itself, opposing the offensiveness of conformist existence through cultivated beauty and detachment.

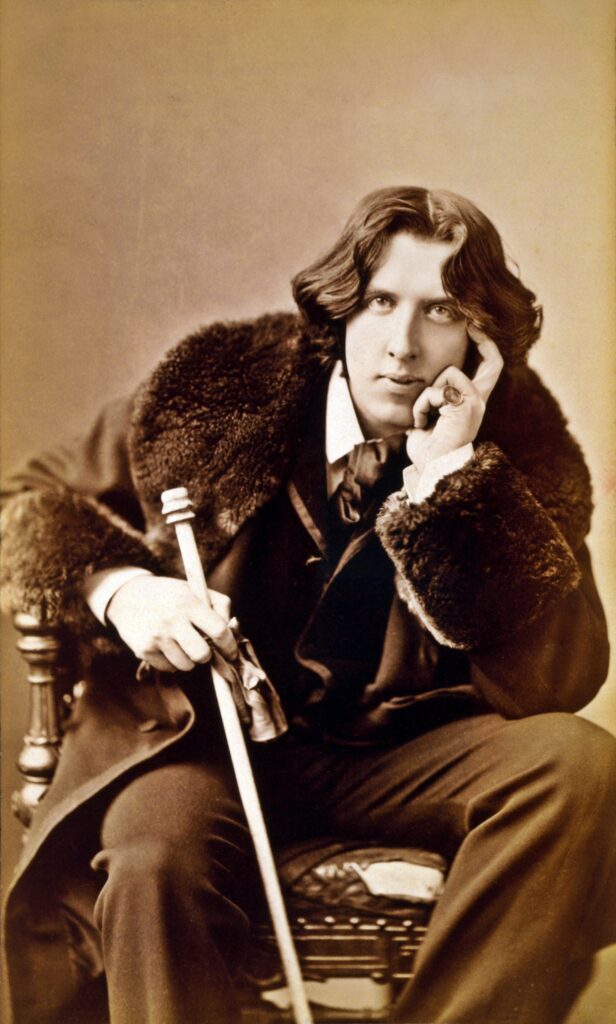

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900): The Irish playwright and aesthete brought Dandyism into the realm of social critique. With his velvet jackets, elaborate boutonnières, and razor-sharp wit, Wilde used fashion as both armor and commentary on Victorian hypocrisy.

Each of these men used Dandyism not as a frivolous pursuit but as a deliberate act of self-definition.

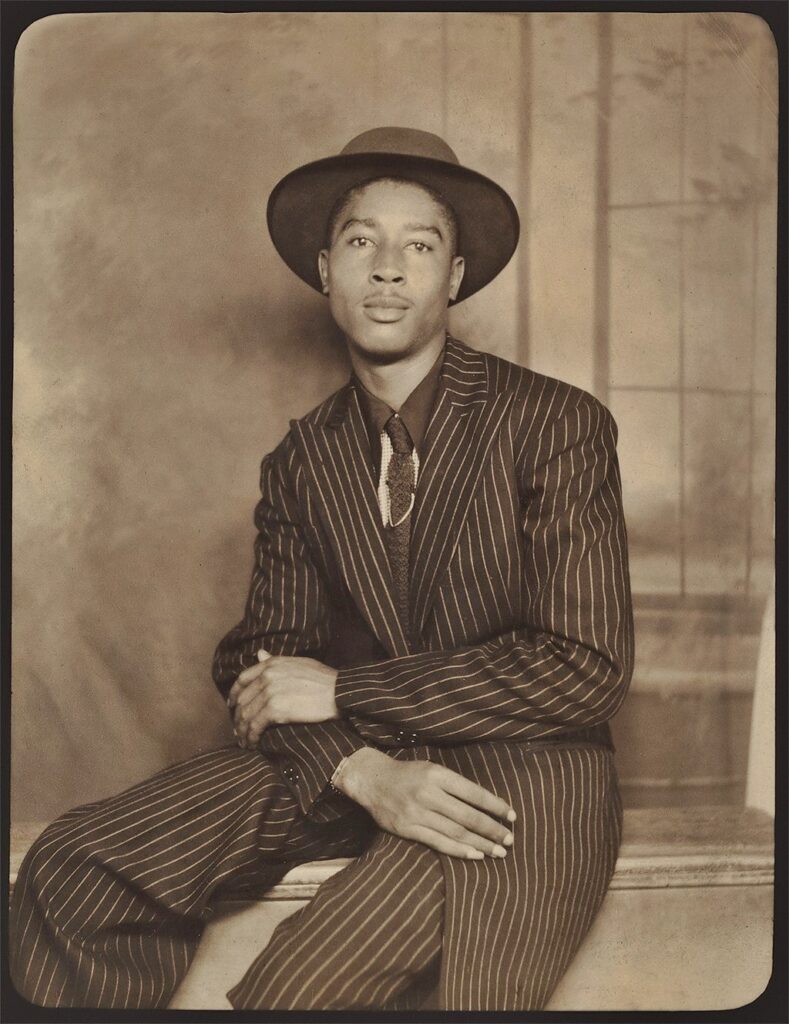

The Black American Dandy

And while Dandyism spread to America and was embraced, it is the tradition of Dandyism in African American culture that has its roots entwined with both survival and self-expression. From the era of slavery through the Harlem Renaissance and into the present day, Black Dandyism has been a powerful means of asserting dignity, challenging stereotypes, and reclaiming the right of beauty and individuality for Black men. This historically rich niche of history could be a blog entry all on its own!

Resistance Through Dress

During the antebellum period, enslaved Africans in America were often denied personal agency, including over their appearance. Yet, when possible, free Black men and even some enslaved individuals used clothing as a subtle but potent form of resistance. Donning fine attire – whether secondhand frock coats, silk cravats, or well-brushed top hats – became a way to assert humanity in a society that sought to deny them it.

For free Black communities in cities like Philadelphia and New York, tailored excellence was a declaration of self-respect and social mobility. Their style mirrored – and sometimes outshone – that of white elites, disrupting racial hierarchies by demonstrating refinement and sophistication. The Black Dandy was not rooted in vanity but was more of a means of asserting self-worth and proclaiming, “I exist. I matter.”

The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond

The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ‘30s marked a golden age for Black Dandyism. Black identity, style, and intellectual life flourished. The “New Negro” movement emphasized pride in African heritage while also embracing the Dandy’s ethos of self-definition through elegance and artistry.

Later, the Civil Rights Movement saw a strategic embrace of dignified dress. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and the Freedom Riders dressed in suits and ties, understanding that presentation could powerfully counter racist narratives of inferiority. Here, the Dandy’s philosophy intersected with activism – style was no longer seen as superficial, but as part of the battle for civil rights.

Contemporary Black Dandyism

Today, the Black Dandy tradition still thrives, blending history with modern sensibility. Contemporary Black Dandies embrace bold patterns, rich colors, sharp tailoring, and a global fusion of influences to continue this legacy. Black Dandyism is not just a nod to the past – it is a living tradition of resistance, creativity, and self-empowerment.

Men’s Fashion Today

The legacy of Dandyism continues into the fashions of the 21st century. Today’s Dandy need not be male or even concerned with traditional menswear. Yet the essence remains: a defiant commitment to personal style, elegance, and self-awareness. The philosophy of the Dandy – that style is a form of individual rebellion against conformity – remains timeless.

In a world where fast fashion reigns and traditionalism often dominates men’s style, the legacy of the Fop, the Macaroni, and the Dandy reminds us that fashion is more than fabric – it is also identity, rebellion, and art.

References:

Janes, Dominic. (2022). British Dandies. Bodleian Library.

Images:

- · “18th Century Fop & Lady.” https://www.paullettgolden.com/post/gentlemen-fashion

- “18th Century Macaroni.” Emily Parrish. https://www.deviantart.com/emilyparrishcostume/art/18th-Century-Macaroni-2-315456478

- “1760 Fop Snuff Box.” https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O156476/snuffbox-ducrollay-jean/

- “1940’s Black Dandy.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/superfine-tailoring-black-style

- “Etching of Beau Brummell.” John Cook. https://www.parisiangentleman.com/blog/dandyism-a-modern-illusion

- “Louis XIV Fop High Heels.” https://imgur.com/high-heels-once-belonged-to-french-king-louis-xiv-S8od52J

- “Macaroni Cartoon.” https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Macaroni-Fashion-Craze/

- “Photograph of Oscar Wilde.” Napoleon Sarony. https://writersinspire.org/content/photograph-oscar-wilde

- “Pink Macaroni Waist Coat.” https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O98553/waistcoat-unknown/

- “Portrait of Charles Baudelaire.” Gustave Courbet. https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Gustave-Courbet/972545/Portrait-of-the-Poet-Charles-Baudelaire.html

- “Portrait of Lord Byron.” Richard Westhall. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw00989/Lord-Byron

- “Young Dandy.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Young Fop.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

- “Young Macaroni.” DALL·E https://chatgpt.com/

Further Reading:

“Black Dandyism Is Back, and It’s Both Oppositional Fashion and Therapy at Once.” Shantrelle P. Lewis. https://matadornetwork.com/life/black-dandyism-back-oppositional-fashion-therapy/

“Dandyism.” Dandyism.net https://www.dandyism.net/

“Dandyism, a modern illusion?” Léon Luchart. https://www.parisiangentleman.com/blog/dandyism-a-modern-illusion

AMAZING writing! Men’s fashion is not a common topic for essays in any arena, so I was thrilled to find it here. Wild to imagine these men of the past dressed up just like the wealthy in Hunger Games. Now I know those visual references were very intentional and far more clever than I was at the time of watching the movie. Brilliant work!

Such a well- written article! Very informative. Now I understand the reference in “Yankee Doodle “.

Thank you for sharing!