Author: Christine Skirbunt

When British archaeologist Howard Carter uncovered the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922, little did he know the impact his find would have on the world. Almost overnight, a wave of “Egyptomania” swept across fashion, design, architecture, and even pop culture. From the glitzy beaded gowns of flappers to bold Art Deco skyscrapers, ancient Egyptian motifs found their way into nearly every aspect of daily life. Women lined their eyes with kohl as Cleopatra once did, adorned themselves with scarab jewelry, and filled their homes with sphinx-shaped figurines. Wealthy socialites hosted lavish Egyptian-themed balls, while Hollywood embraced exoticized depictions of pharaohs and goddesses. The 1920s Egyptian Revival was not merely an artistic trend – it was a cultural phenomenon, blending the mystique of ancient Egypt with the modern glamour of the Jazz Age.

The Three Revivals: Napoleon, the Suez Canal, and King Tut

Egyptian Revivalism wasn’t a new phenomenon in the 1920s. Western fascination with ancient Egypt had already surged twice before: first with Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt (1798-1801) and again with the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Napoleon’s scientists and artists thoroughly documented ruins, artifacts, and hieroglyphs in Egypt. This led them to discover the Rosetta Stone and, in doing so, created the field of Egyptology. This sparked a wave of interest in Egyptian motifs in architecture and design throughout Europe and America but, except for the very wealthy, it was not a mainstream fascination available to all. The opening of the Suez Canal brought another flood of Egyptian-inspired art and design, as global travel and trade further exposed Western elites to the grandeur of Egypt’s past.

But it was the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 that sent the world into a full-blown Egyptomania unlike any before.

Why the 1920s Egyptian Revival Was Different

The Egyptian Revival of the 1920s wasn’t just about architecture and high society fascination as the first two Revivals had been. This one permeated everyday life in a way the previous Revivals hadn’t. The 19th-century Revivals had been largely academic and aristocratic, influencing grand buildings (i.e. the Washington Monument – begun in 1848), and a handful of fashion trends among the privileged. The 1920s Revival differed, however, in that it was fueled by mass media, Hollywood, and the excitement of modernity. These things made Egyptian motifs accessible to the middle class through fashion, home decor, and even cosmetics. By looking to ancient Egypt, “Americans sought something permanent to hold onto in an era of rapid change, as well as a place to escape when the present became too overwhelming.” (Hunt, 2003)

Howard Carter and the Discovery of King Tut’s Tomb

Fascination with Ancient Egypt has existed since the days of the ancient Romans, who carted monuments like giant obelisks back to Rome where, even today, there are more Egyptian obelisks in Italy than in Egypt (Egyptian Revival: An Obsession with the Ancient World). So, in November of 1922, with the inadvertent help of his unsung water boy, Hussein Abdel-Rassoul, when British archaeologist Howard Carter uncovered the tomb of Tutankhamun – an 18-year-old pharaoh who had ruled Egypt over 3,000 years earlier – the world was eager for more information. Unlike other tombs that had been discovered only to be found looted, Tut’s resting place was untouched, filled with a golden chariot, jeweled daggers, statues, and the now-iconic golden death mask.

The discovery was sensationalized in newspapers across the world. For months, headlines were filled with details of the treasures, Carter’s findings, and eerie rumors of a “curse” striking down those who entered the tomb. This only heightened the mystique surrounding Egypt, fueling an obsession that spread through popular culture.

Art Deco: What It Is and How Egyptian Revival Fit In

Art Deco, the defining design movement of the 1920s and 1930s, was characterized by bold geometric patterns, symmetry, sleek lines, and luxurious materials like gold, ivory, and lacquer. It emphasized modernity while borrowing from ancient influences, making Egyptian motifs a perfect match.

Egyptian symbols – scarabs, pyramids, obelisks, and sphinxes – became prominent in jewelry, furniture, architecture, and fashion. The clean, angular aesthetics of Egyptian hieroglyphs and temple carvings blended effortlessly with Art Deco’s sleek, modern appeal. Art Deco allowed the Egyptian Revival to take place in a very overt manner. Almost anything Egyptian-themed could be combined with Art Deco.

Egyptian Revival Clothing, Jewelry, Make-Up, and Hair

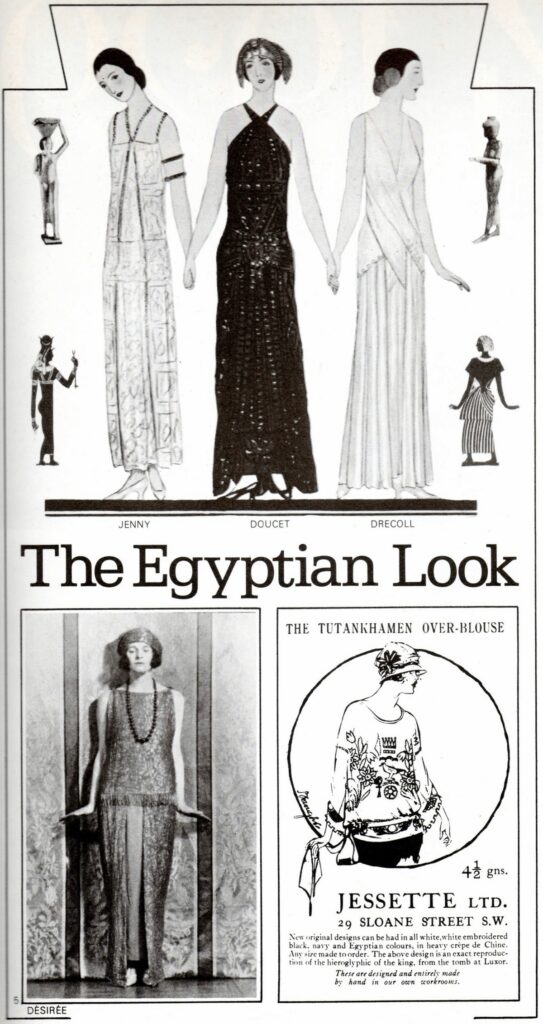

It seems nearly everyone was ready to jump on the Egyptian Revival wave to either make money or be fashionable. As early as January 1923, less than two months after Carter’s discovery, the Avedon Clothing Store in New York City was selling the pleated “Cleopatra” skirt for $19.95 – $352.97 in 2025 prices!

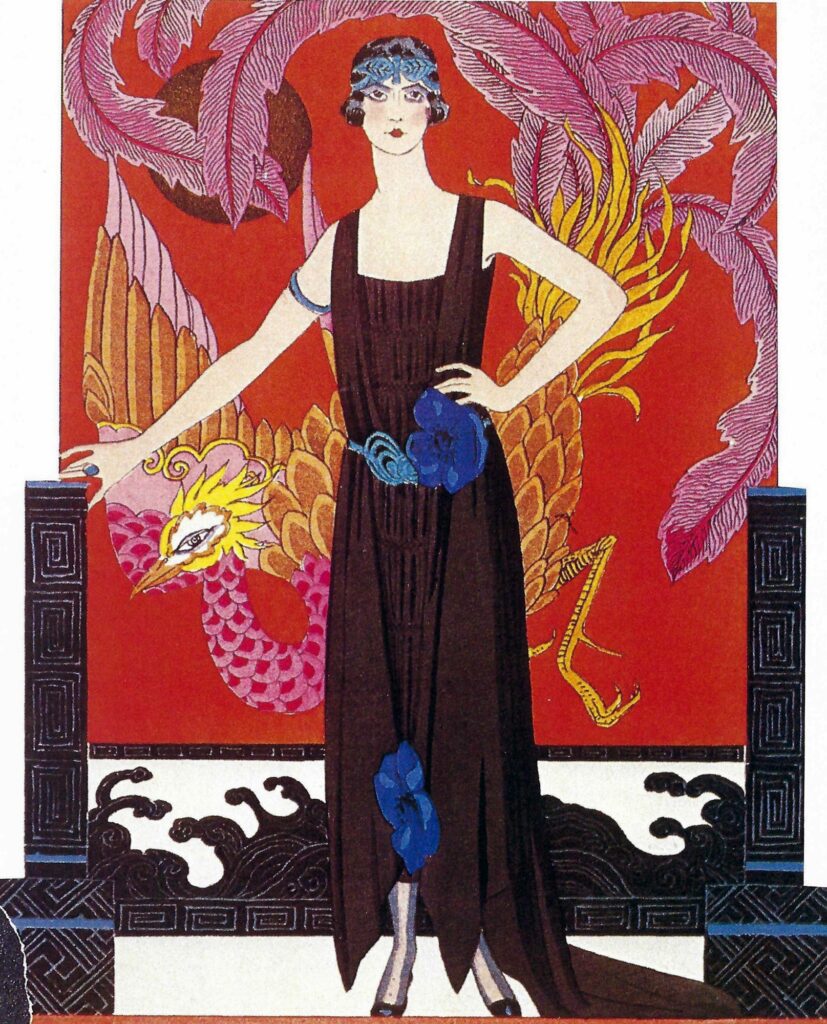

While flappers of the 1920s embraced drop-waist dresses, knee-length skirts, and beaded embellishments, Egyptian Revival fashion took this a step further, incorporating exotic details inspired by ancient wall paintings and tomb artifacts.

- Dresses: Egyptian Revival gowns featured columnar silhouettes, mimicking the tunics and draped garments seen in Egyptian art. Unlike standard 1920s dresses, these had bold gold embroidery, intricate beadwork, and printed hieroglyphic motifs. Many were sleeveless or had beaded capes, imitating the regal look of Egyptian royalty. The most popular fabric was crepe de chine, often in silk.

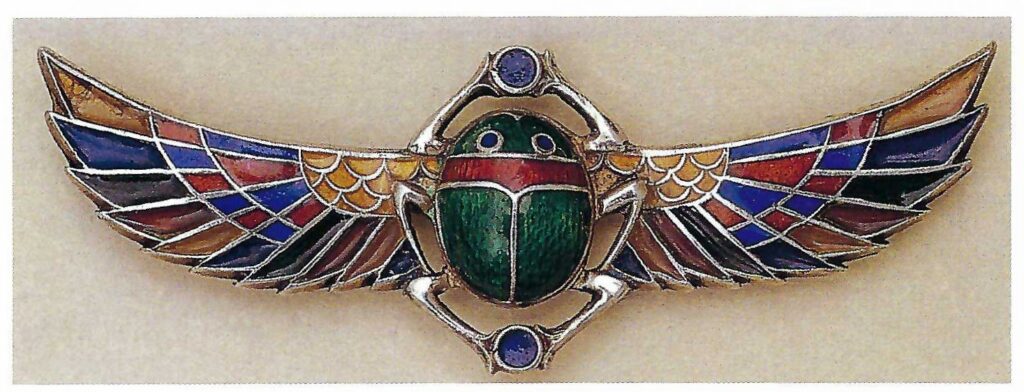

- Jewelry: Statement pieces were necessary. Women wore wide gold cuffs, snake armbands, beaded collars, pendants shaped like scarabs, Ankhs, and the Eye of Horus. From bracelets, necklaces, earrings, brooches to hat pins – all could, and were, made Egypt-themed. For the wealthy, favorite materials were onyx, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, lapis lazuli, and enamels set in silver, platinum, and gold. Cheaper imitations were readily available for the women who couldn’t afford the high-end price tags.

- Make-up & Hair: Egyptian Revival make-up popularized kohl-rimmed eyes, inspired by depictions of Cleopatra and goddesses. Women used deep blue, green, and gold eye shadows, darkened their brows, and often wore heavily stylized bob cuts reminiscent of ancient Egyptian wigs. Lips were painted deep red or plum, with a sharp cupid’s bow. The 1920s Egyptian Revival was not concerned with respectfully or even truthfully depicting foreign culture but was very keen on borrowing motifs loosely. (Egyptian Revival: An Obsession with the Ancient World)

The Expansion of the Egyptian Revival into Everything

This obsession wasn’t limited to fashion—it expanded into nearly every aspect of daily life, including:

- Furniture & Interior Design: Homes featured sphinx-shaped bookends, scarab-themed wallpaper, and pyramid-inspired lamps.

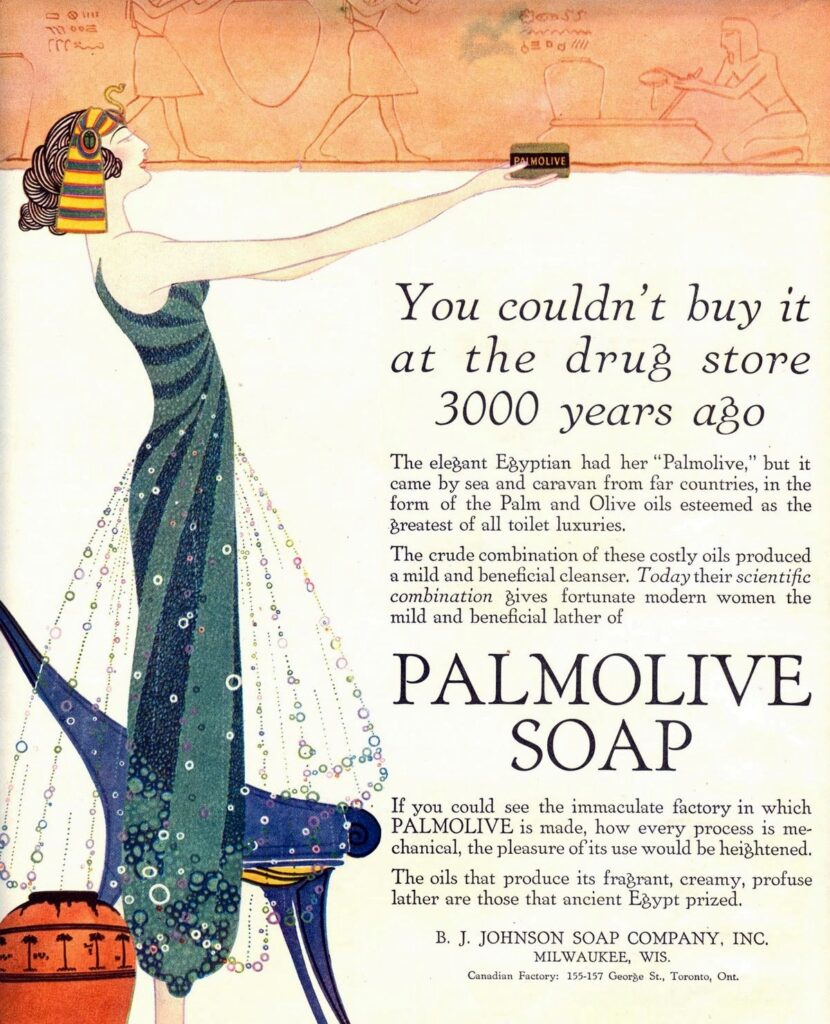

- Perfumes & Soaps: Luxurious beauty products sprang up, as well as more common products, such as Palm Olive Soap, which first came out in 1898, saw a marketing opportunity, and took it.

- Movies & Theatre: Hollywood capitalized on the Egyptian trend with films. Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Ten Commandments” (1923), showcased elaborate Egyptian-inspired costumes and sets.

- Advertising & Branding: Everything from cigarette tins to hotel logos adopted Egyptian symbols to appear fashionable and exotic.

The Wealthy Cosplay and LARP in the 1920s

One of the most extravagant aspects of the Egyptian Revival was the lavish costume balls held by high society. Wealthy elites hosted “Egyptian Balls” and “Nile Soirées”, where attendees dressed as Cleopatra, pharaohs, or gods like Anubis and Isis:

- Guests were expected to stay in character, addressing each other with royal titles.

- Ballrooms were transformed into mini-Egyptian temples, with palm trees, sphinx statues, and golden thrones.

- Some parties even staged mock ceremonies, complete with ritualistic dancing and elaborate theatrical performances.

These balls were set apart from the everyday Egyptian Revival by the participants’ adherence to archaeologically correct fashions and mannerisms. This was, in essence, a form of early cosplay and LARP (Live Action Role-Playing), where wealthy attendees immersed themselves in the fantasy of ancient Egypt for a night of luxury, spectacle, and pretend.

What Replaced Art Deco and the Egyptian Revival?

By the mid-1930s, Art Deco and the Egyptian Revival began to fade, replaced by more streamlined, functional styles like Art Moderne and Bauhaus. The Great Depression and looming war years further shifted the focus from ornate, exotic aesthetics to simpler, more practical designs.

References:

Azzarito, Amy. “Egyptian Revival: An Obsession with the Ancient World.” Erica Weiner. https://www.ericaweiner.com/history-lessons/egyptian%20revival

Herald, Jacqueline. (2007). Fashions of a Decade: The 1920s. Chelsea House Publishers.

Hunt, Katherine A. (2003). “Beauty that endures”: Egyptian revival in the 1920s. Master’s Theses. University of Delaware.

Images:

- · “1923 The Egyptian Look.” https://ar.pinterest.com/pin/154248355978506525/

- “Ladies Home Journal, Palm Olive Soap.” https://de.pinterest.com/pin/343188434102237101/

- “1920s fully sequined dress on tulle in an Egyptian Revival design of gold, blue, and iridescent.” https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/175147873002062907/

- “1923 Bradley’s Egyptian influenced beaded lame evening dress.” https://www.pinterest.com/pin/259871840975074800/

- “1924 Norman Hartnell Evening Gown with Ostrich Plumes.” Herald, Jacqueline. (2007). Fashions of a Decade: The 1920s. Chelsea House Publishers.

- “Augusta Auctions by Edith Hyde.” https://augusta-auction.com/auction?view=lot&id=121114333&auction_file_id=139

- “1920, Nazli Sabri, Queen of Egypt.” https://www.pinterest.com/pin/363173157448249254/

- “1926, National Geographic: How King Tut Conquered Pop Culture.” https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/how-king-tut-conquered-pop-culture

- “1923, Doucet, photo by Henri Manuel.” https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/524387950347357068/

- · “1920s German silver and enamel scarab brooch.” Herald, Jacqueline. (2007). Fashions of a Decade: The 1920s. Chelsea House Publishers.

- “1920s Art Deco Egyptian Revival Enamel Carved Earrings.”

- “Scarab belt buckle, 1926, Cartier.” https://www.hodinkee.com/articles/unique-mystery-clock-cartier-cooper-hewitt-museum

Further Reading:

Higgs, Levi. “The Eternal Appeal of Egyptian Revival Jewelry.” The Adventurine. https://theadventurine.com/culture/jewelry-history/the-eternal-appeal-of-egyptian-revival-jewelry/

Ickow, Sara. (July 1, 2012). “Egyptian Revival.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/erev/hd_erev.htm

Thank you, Elizabeth! We are glad that you enjoyed it!

This is my favorite writing of yours yet. I had NO idea about this wild spread of influence, all from Egyptian ancient history. Absolutely incredible! So well written and referenced. Please keep writing!