Author: Christine Skirbunt

“What greater gift than the love of a cat.”

–Charles Dickens

Old maid. Spinster. Crazy Cat Lady. All words used to describe single women through the centuries who dared to be unwed and have a cat as a companion. The stereotype of the “cat lady” conjures vivid imagery: a solitary woman surrounded by furry companions, “sad and lonely…who uses felines as a substitute for both lovers and children.” (How the ‘Crazy’ Cat Lady Became One of Pop Culture’s Most Enduring Sexist Tropes) Yet, this continuing cultural archetype has roots far deeper, and far more nuanced, than modern pigeon-holes suggest. Indeed, tracing the “cat lady” trope’s history reveals a rich tapestry stretching from ancient reverence, to ridicule, and now to today’s reclamation and empowerment of the title.

Ancient Veneration

Long before the “crazy cat lady” became a humorous or derogatory label, cats held revered status, particularly within ancient cultures where femininity and felines were intertwined in sacred association.

In Ancient Egypt, cats were worshiped as divine beings and strongly associated with the cat goddess Bastet. Bastet symbolized domesticity, fertility, and feminine grace while cats in general were highly venerated for their protective qualities. They were the guardians of the human household who safeguarded families from rodents and snakes. Women especially formed deep connections with these sacred animals, seeing them as companions in both spiritual and everyday life. Cats were treated with religious reverence and emotional affection.

Norse mythology presented Freya, the goddess of love and fertility, traveling in a chariot pulled by two majestic cats. This rendition of her reinforces the feline-female connection and is echoed in other ancient cultures.

Yet, this reverent relationship between women and cats faced dramatic transformation with the rise of European Christianity.

The Middle Ages

As Medieval Europe became increasingly governed by Christian belief, the church viewed cats as a threat because cats had firmly held connections to old pagan religions and were still respected by many people. The church wanted to stamp that out. Cats, once sacred, were now depicted as evil, particularly black ones. The cat came to symbolize malevolence and witchcraft, becoming victims (along with women) of suspicion and superstition. Women who lived alone and kept cats faced especially harsh scrutiny.

In 1486 the infamous witch-hunting guide, the Malleus Maleficarum, was written by the German Dominican friar Heinrich Kramer – a man who was considered so extreme concerning his views of women, witches, and how to eradicate them that he was once forced by a local bishop to leave the region after the bishop condemned Kramer’s practices against women and declared him mentally unfit.

But the damage was done, and Kramer’s book became the go-to source for hunting witches. The association of single women with cats was solidified into sinister folklore. Women living independently – especially widows and spinsters – who owned or cared for cats were often accused of witchcraft and their feline companions were labeled as familiars who aided in their unholy deeds. This created a lasting and destructive stigma for both women and cats. And it was a legacy that would linger in cultural memory, fueling suspicion and fear for generations.

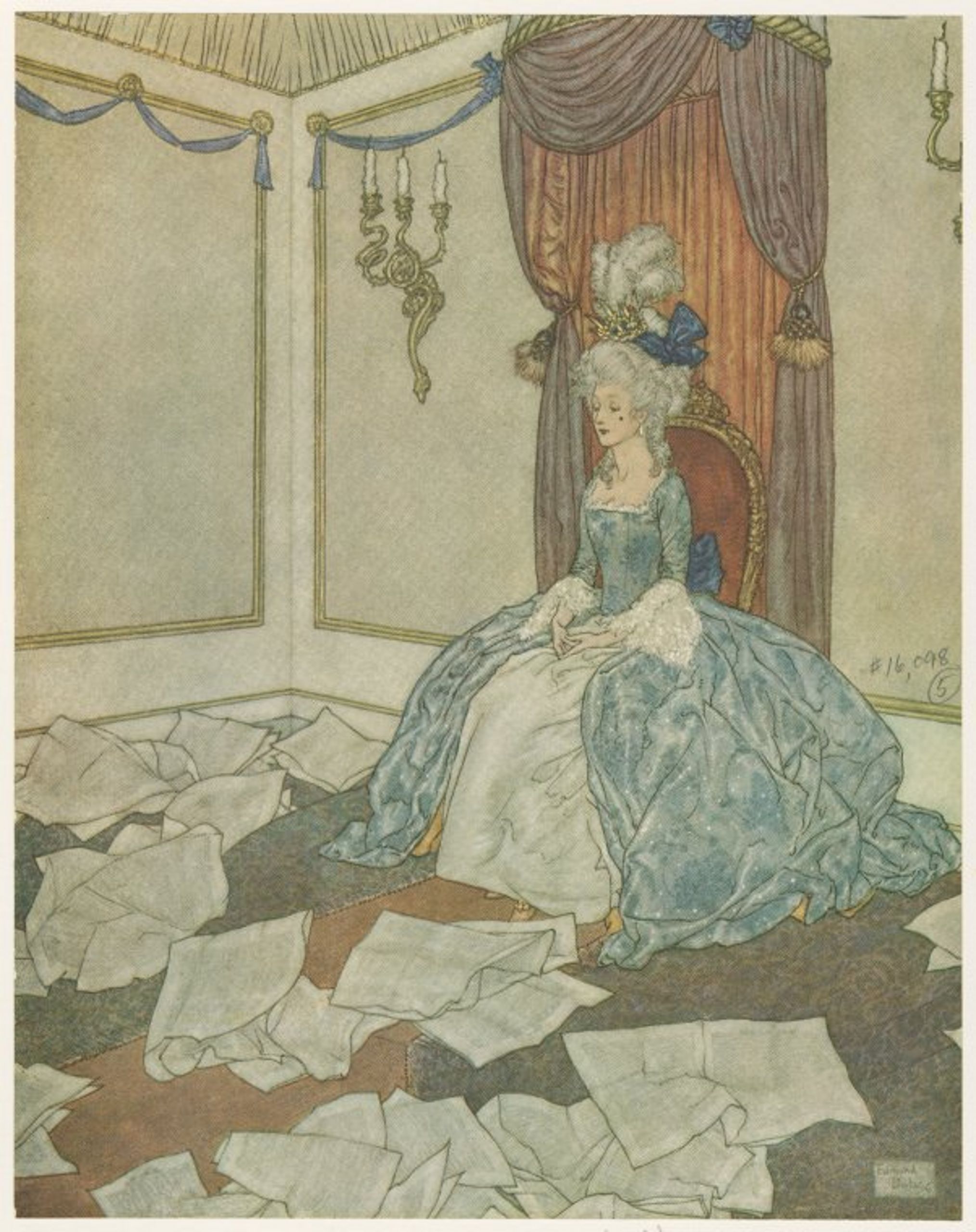

The Age of Enlightenment

By the 18th century, the label of “witch” had faded. Yet stigma around single, independent women and their cats persisted despite it being an “enlightened age.” But instead of fearing these women, they were now to be pitied. Unmarried women without children often had to rely on their family for support. This frequently built a level of resentment both towards the woman and any innocent cat she may have shared her days with. Both were seen as a burden.

The 1789 satirical print Old Maids at a Cat’s Funeral was a perfect example for the attitudes of the time. The image is of a cat funeral depicted with mock-seriousness, poking fun at the idea that the women portrayed cared more for cats than people. It circulated for years and helped shape the enduring stereotype of “crazy cat ladies” – women considered too old, too single, and too emotionally invested in their cats.

The Victorian Era

However, in the 19th century, cats began to receive much more respect and recognition as valid pets as the atmosphere around them changed. England’s increasing wealth in the 19th century made for an environment of an “expanding middle class with money to spare and aspirations for living like the upper classes.” This included the keeping of pets which before had been seen as a “wasteful extravagance” that only the rich could afford. (The Rise of Cats and Madness: III. The Nineteenth Century) This leant to the attitude that pet ownership was a sign of moral virtue rather than that of corruption or scorn.

The “Cult of Pet-Keeping” was firmly established by the mid-19th century and was due in large part to Queen Victoria, who ascended the throne in 1837. Under her rule, she set new standards for keeping royal pets. She is known to have had 88 different pets during her long reign and each and everyone of them had a name. And while many of her pets were dogs, she also kept cats, the most famous being a Persian cat she named “White Heather.” By publicly embracing cats, Victoria helped legitimize them as pets, especially for women, and encouraged their presence in middle- and upper-class homes. The rational was simple: if the Queen of England kept cats as pets, then surely their Medieval stigma and Enlightenment disdain were outdated modes of thinking. In fact, the cat soon became identified as part of the ideal Victorian home and an embodiment of domestic virtue!

Famous Victorian Cat Owners

Truly, the Victorian Era was a much happier age for cats than it had been for hundreds of years. Many famous writers, poets, painters, and philosophers owned cats. The famous nurse and reformer, Florence Nightingale, owned more than 60 in her lifetime (all strays she took in from the streets) and claimed, “they possessed much more sympathy and feeling than human beings.” (The Rise of Cats and Madness: III. The Nineteenth Century)

Other famous Victorian cat owners included John Keats (who wrote Sonnet To A Cat), Percy Bysshe Shelley (whose first known poem at age ten was Verses on a Cat), and Lord Byron, who owned at least five cats at one time. The list goes on as poet William Blake was noted to prefer cats to dogs. And Charles Dickens had the comical experience of a favorite cat, William, later giving birth to kittens and was thus promptly renamed Williamina. The Bronte sisters were also well-known cat-lovers. Emily Bronte authored an essay titled The Cat in which she noted, “I can say with sincerity that I like cats, also I can give you very good reasons why those who despise them are wrong.” (The Rise of Cats and Madness: III. The Nineteenth Century)

Robert Southey, Poet Laureate of England from 1813-1843, kept many cats. When one of his favorite cats died, Southey wrote a friend, “I believe we are each and all, servants included, more sorry for his loss, or rather affected by it, than any one of us would like to confess.”

Even on the other side of the Atlantic in America, cats were entering into the human love affair of having a cat for companionship rather than just for pest control. Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain) was a devoted lover of cats. He shared this love with his mother and then carried it over into his own life when he had his own family. It was well-known that Clemens indulged his passion for cats freely and once wrote to his wife while she was away visiting family that the cats had “the run of the house. I wouldn’t take thousands of dollars for them. Next to a wife I idolize, give me cat.” (Grier 2006)

The Ultimate Cat Lady Tribute

One notable historical piece of evidence that cats were becoming beloved by more than just “cat ladies” was the rise in paintings featuring cats. And while some of the best-known cat paintings of the 19th century were those of Pierre-Auguste Renoir (think Woman with a Cat, Sleeping Girl with a Cat, and Julie Manet with a Cat), it was Austrian artist Carl Kahler’s famed painting, “My Wife’s Lovers” (1891-93) that is the undisputed winner of cat paintings.

Kate Birdsall Johnson, a wealthy California philanthropist and avid cat enthusiast, commissioned the artwork by Kahler to immortalize her cherished pets. The painting took three years to complete and is 6’x8.5’ with a canvas that weighs 227lbs. The painting features an astounding 42 of Johnson’s Turkish Angora and Persian cats in grandiose and affectionate detail.

Rather than portraying Johnson herself, Kahler’s painting celebrates her passion directly, capturing the personalities of each cat vividly. The artwork was a milestone in honoring the loving bond women shared with their feline companions, reframing the narrative as it being something to be admired rather than mocked.

“My Wife’s Lovers” survived the devastating San Francisco earthquake of 1906 while the gallery it was in at the time was almost completely destroyed. The painting, which fetched Kahler $5,000 in 1891, sold at Sotheby’s for an astounding $826,000 in November 2015 to a private collector. (Wikipedia)

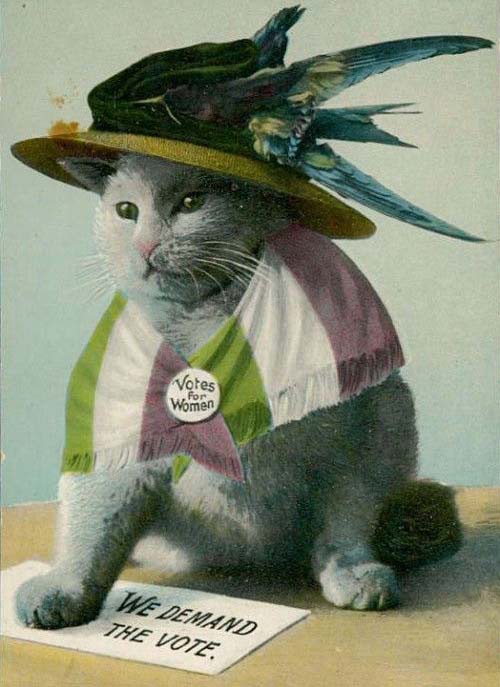

Cats and Women’s Suffrage

Amid the evolving perceptions of the 19th century, cats played a surprising and symbolic role during the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century. Sadly, anti-suffrage propaganda fell back on old “cat lady” tropes and often depicted suffragists as women who were man-haters and eccentric – frequently accompanied by cats. These portrayals attempted to diminish the seriousness of women fighting for their rights and suggested that the desire for independence equated to loneliness or abnormality. It was a blatant nod to associate women’s rights activists with cats and to act as a warning to the public about what “type” of woman really wanted the vote: a spinster man-hater with too many cats and no husband to help “guide” her into voting the “correct way” (i.e.: how her husband voted).

Yet suffragists cleverly reclaimed the cat image and used cats to their advantage. Cats became symbols of independence, self-sufficiency, and dignity. Women began proudly posing for photographs with their feline companions in celebration of the cats and themselves. The campaign worked and effectively subverted a negative stereotype into a powerful symbol of self-sufficiency and solidarity. Cats thus transitioned from stigmatized companions to iconic allies in the fight for gender equality.

Mid-20th Century Representations

As the 20th century progressed, the media sadly became an influential vehicle in shaping and reinforcing the “cat lady” stereotype. Sitcoms and cartoons further simplified this archetype. Popular shows such as The Simpsons introduced the iconic Crazy Cat Lady character – a mumbling incoherently woman with a panache for throwing cats at bystanders. This image and others like it helped reestablish the sad, single woman living alone with only cats for company back into popular consciousness. But not for long.

The Modern Reclamation

Fortunately, the 21st century has witnessed a vibrant reclamation and reframing of the “cat lady” typecast. Today, for many, the image of a woman proudly living independently and lovingly caring for cats has become not only normalized but celebrated.

Cats are important muses for today’s fashion designers and often end up in advertisements or editorials alongside human models more frequently than dogs. This is because cats are now associated with grace, independence, sensuality, and mystery – all qualities designers and stylists often aim to evoke in women’s fashion. Cats also bring whimsy and unpredictability, as is seen in the coveted 2005 September issue of Vogue by famous photographer Tim Walker’s editorial “Fuzzy Logic” alongside red-headed beauty and cat-lover herself, supermodel Karen Elson. In it she is surrounded by dozens of cats and beautifully dressed. The editorial almost asks, “are the cats the accessories or is Elson?”

Events like CatCon – a lively convention that gathers tens of thousands of feline fans annually since it first debuted in 2015 – has also significantly reshaped the public perception of the “cat lady”. Attendees proudly embrace their feline affinities, showcasing that cat companionship is modern, joyful, and socially embraced. In fact, among Millennial cat-owners, at least, more men own cats than women (48% of men vs 35% of women). (How the ‘Crazy’ Cat Lady Became One of Pop Culture’s Most Enduring Sexist Tropes)

Embracing the “Cat Lady” Identity Today

Ultimately, the evolution of the “cat lady” stereotype: from sacred reverence to Medieval suspicion, Enlightenment pity to Victorian fascination to today’s contemporary positive reclamation, speaks volumes about cultural attitudes toward women, independence, and companionship. But what truly connects every period mentioned above is that the stigma really has less to do with the animals but more about a deep-rooted fear of powerful female goddesses, evil witches, and worry over single women voting how they wanted. Today’s “cat ladies” assertively redefine their image: confident, independent, emotionally intelligent, and compassionate. The cultural narrative has moved from derision to empowerment, proving that independence and affection – whether towards humans or beloved pets – are strengths to be embraced.

The future, indeed, belongs proudly to the cat ladies.

References:

Grier, C. Katherine. (2006). Pets in America: A History. Harcourt Publishing.

Rae Alexandra. (February 8, 2021). “How the ‘Crazy’ Cat Lady Became One of Pop Culture’s Most Enduring Sexist Tropes.” KQED. https://www.kqed.org/arts/13891913/how-the-crazy-cat-lady-became-one-of-pop-cultures-most-enduring-sexist-tropes

Madison Arnold-Scerbo. (July 26, 2017). “Cats & Women: Why the Connection?” Biodiversity Heritage Library. https://dfordreadful.wordpress.com/history/

E. Fuller Torrey. (November 30, 2021). “The Rise of Cats and Madness: III. The Nineteenth Century.” Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-86811-6_5

N/A. (n.d.). “The History of the Domestic Cat.” Alley Cat Allies. https://www.alleycat.org/resources/the-natural-history-of-the-cat/

N/A. (n.d.). “My Wife’s Lovers.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Wife%27s_Lovers

Images:

- · “20th Century Votes For Women Cat.” KQED. https://www.kqed.org/arts/13891913/how-the-crazy-cat-lady-became-one-of-pop-cultures-most-enduring-sexist-tropes

- “1789 Old Maid’s At Cat’s Funeral.” KQED. https://www.kqed.org/arts/13891913/how-the-crazy-cat-lady-became-one-of-pop-cultures-most-enduring-sexist-tropes

- “1874 Renoir Woman with a Cat.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman_with_a_Cat_%28Renoir%29

- “1893 Kahler My Wife’s Lovers.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Kahler_-_My_Wife%27s_Lovers.jpg

- “2021 Thomas Hopes You Like Cats.” Author’s Collection.

- “June 2016 Harpers Bazaar UK Kittens With Kitten Heels.” Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/266908715394862729/

- “Karen Elson Photographed by Tim Walker September 2005 Vogue US 01.” Pleasure Photo. https://pleasurephoto.wordpress.com/2013/09/09/karen-elson-photo-tim-walker-vogue-september-2005/

- “Karen Elson Photographed by Tim Walker September 2005 Vogue US 02.” LiveJournal. https://katia-lexx.livejournal.com/1627580.html

- “The Simpson’s Crazy Cat Lady.” Fine Art America. https://fineartamerica.com/featured/simpsons-crazy-cat-lady-01-chung-in-lam.html?product=greeting-card

Further Reading:

“Photos: From the Archives: Cats in Vogue.” Vogue Magazine. https://www.vogue.com/slideshow/from-the-archives-cats-in-vogue-photos

“CatCon.” THE Cat Convention. https://www.catconworldwide.com/

“Cats and the Salem Witch Trials.” Cunning Folk. https://www.cunning-folk.com/read-posts/the-cats-of-old-salem

The title of this piece truly does not do justice to this majestic writing. Who knew that cats played such powerful roles in politics, perceptions, and power? (Besides the cats, of course.) Meow!

A comprehensive, fresh, well-researched article, Ms. Skirbunt. A thoroughly enjoyable read.