This year marks the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, which went down on April 14th, 1912. No other maritime disaster has captured the public’s attention like this one. The story of her sinking continues to be the subject of stage, cinema and literature. While this may well be the greatest maritime disaster in our history, we can now look back and see how this terrible tragedy became the catalyst for sweeping changes in maritime laws which have prevented this type of event from ever happening again.

Immediately after the news of the Titanic’s sinking, committees were formed both in the United States and Britain to investigate the causes of the disaster and take steps to ensure that it was never repeated. In America, Senator William Alden Smith organized an inquiry. Senator Smith had already been responsible for a great deal of railroad safety regulations passed by Congress. In Britain, Lord Mersey, who was the Commissioner of Wrecks, headed up the inquiry. While the United States inquiry was focused on how the disaster happened, the British inquiry wanted to understand why it had happened. Both groups spent weeks interviewing ship’s officers and passengers. Both American and British inquiries would finally make several similar recommendations aimed at ensuring greater safety at sea. In addition to general safety recommendations, several specific areas addressed were the conduct of wireless operators, the actions to be taken by ship’s captains in the presence of ice, lifeboat regulations, and shipbuilding codes.

A practical working wireless telegraph had been developed and demonstrated in 1901 by Gugliemo Marconi. His wireless was able to transmit signals across the Atlantic, creating a worldwide sensation. Marconi himself promoted the greatest benefit of his system as, “…the facility which it affords to ships in distress of communicating their plight to neighboring vessels or coast stations.” Shipboard wireless became immensely popular and soon several separate wireless companies were established in major competing countries. With no regulations to guide them, competition for paid radio traffic was fierce, and operators from rival companies would not acknowledge each other, and even went so far as jamming each other’s signals. There was no standard telegraph equipment, two Morse languages in use, no laws concerning when the wireless must be manned, and no place for the wireless operators among the ship’s crew. Titanic was equipped with state-of-the-art wireless equipment – the most powerful in use at the time. While most ships so equipped had only one operator, the Titanic boasted two men. John “Jack” Phillips and Harold Bride were not considered ship’s officers, and even wore different uniforms – that of the British Marconi Marine. They were employed by Marconi, not the White Star Line, and paid primarily to relay messages to and from the passengers; they were not focused on relaying “non-essential” ice messages to the bridge. Indeed, in the four days since leaving port they had sent and received two hundred and fifty telegrams – most to and from passengers. After investigation into the disaster, the Radio Act of 1912 was passed in America, which provided for licensing of wireless operators, and division of certain bandwidths for communication. Amateurs were allowed to listen, but not to transmit on any bandwidths except the very shortest, which were then considered useless. A similar law passed in Britain went even further and stipulated that all ships must have wireless communications, and must also carry trained operators.

Navigation in ice fields was another area that was changed after the Titanic disaster. It was not common for ships to collide with icebergs. Prior to the Titanic, it had been forty years since any ship had suffered severe damage in this way. Even then there had been no loss of life. In 1913 an international conference on safety at sea was held in London. The result was the establishment of a permanent ice patrol in areas deemed the most dangerous to shipping. The United States Coast Guard assumed responsibility of running the International Ice Patrol (IIP). At first cutters were used for this job, then airplanes. In the 100 years since the implementation of the IIP, no ship that has heeded its warnings has been lost or damaged near the Grand Banks. Every year on April 15th the chart transmissions sent out by the IIP mark not only the current positions of icebergs, but also the location of the Titanic’s final resting place.

Both American and British inquiries resulted in several recommendations about lifeboat regulations. Titanic was fully compliant – and even exceeded – the regulations of the day, yet carried only enough lifeboats to accommodate about half the compliment of passengers and crew. The American committee proposed that every ship carry enough lifeboats to carry all passengers and crew – a measure that was already being implemented in the wake of the Titanic’s sinking. British plans were much more detailed and not only involved the number of lifeboats, but also mandated personnel who knew how to operate them and scheduled drills to demonstrate readiness for a disaster. Finally, they mandated that the Board of Trade conduct “strict and searching” inspection of lifeboats.

The need to revise shipbuilding regulations was mandated as well. Both American and British recommendations included new standards for watertight compartments, and bulkheads. Consideration was also given to the creation of watertight decks above the waterline. No ship was to be licensed to carry passengers from American ports until it conformed to the rules and regulations set forth by law. In addition steamships that carried more than 100 passengers were to have two electric searchlights to aid in the detection of ice and other potential obstacles. In the following years American and British recommendations were passed into law by nations around the world.

This year, the cruise ship Balmoral, operated by Fred Olsen Cruise Lines has been chartered by Miles Morgan Travel to follow the original route of Titanic, intending to stop over the point on the sea bed where she rests on 15 April 2012.

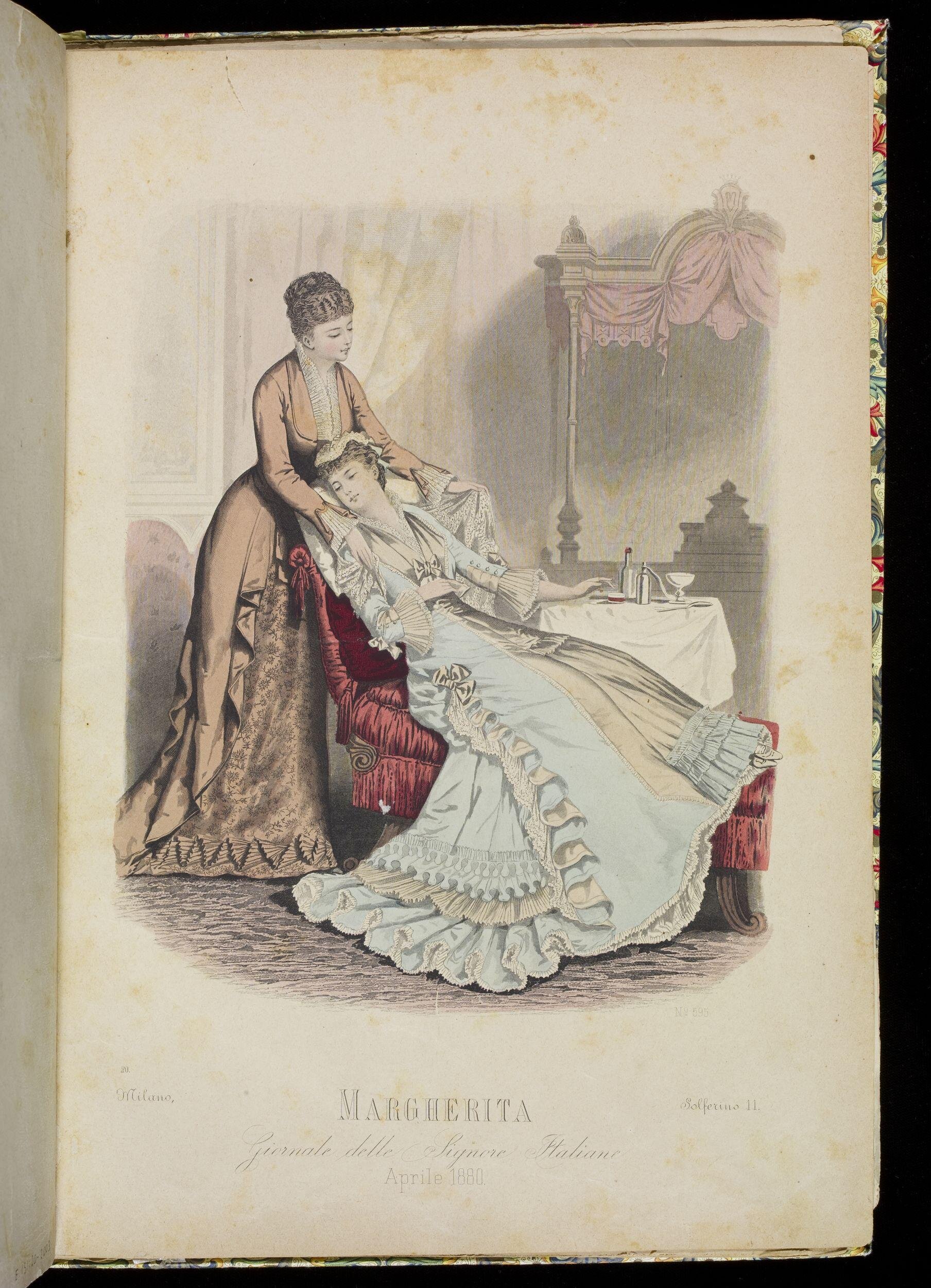

[…] Whether you will be participating in a cruise or attending an event on the shore, Recollections thought you would like to know how to dress for each occasion, so they have written these two informative articles on their blog for your perusal – Dressing for the Titanic and 100 Years after the Sinking of the Titanic. […]

[…] 100 Years after the Sinking of the Titanic […]

Oh yes! I have had the last dinner on the Titanic – at the Durango Heritage Celebration last October – and it is truly an elegant and fabulous meal. (Sigh) Yet one more reason to yearn to spend a weekend at the fabulous Grand Hotel. So let’s all break out our best Edwardian dinner gowns (better yet – check out the newest offerings on the Recollections site) and make a reservation right away!

Anyone who would like to relive an historically-accurate recreation of the Last Dinner on Titanic is welcome to attend “Titanic at the Grand”, May 4-6, 2012, at the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island. Events will include Titanic historians, a showing of the 1953 Titanic movie (in which several passengers were bound for Mackinac), a vintage fashion show, and the dinner served on April 14th, 1912, complete with an interactive theatre presentation – you too can dine with the Unsinkable Molly Brown, the Astors, and others! Edwardian costuming prevails throughout the weekend, so pick up your favorite Recollections dress and join us! For more information and reservations, visit:

http://www.grandhotel.com/specials/packages/may/titanic-at-the-grand

But better reserve soon – last year’s passage sold out in just 3 weeks!