Author’s Note:

As I once said before, my aim is to stay behind the scenes here and let the history speak. This is a rare exception where I briefly insert my voice because the trail that led to this article is a rabbit hole many Recollections readers have traveled or plan to explore.

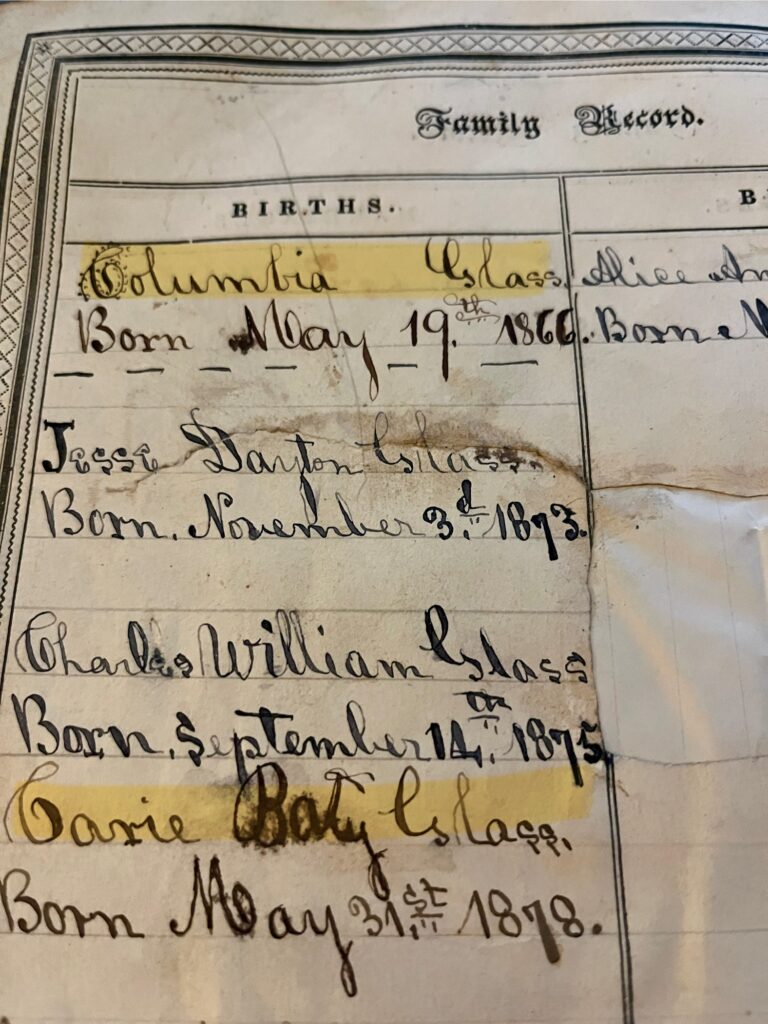

On my maternal side, family records were kept with care. I haven’t joined the DAR yet, but I intend to, out of respect for American history and my family’s part in it. One ancestor in particular lit the fuse: Columbia Glass (left), pictured with her half-sister, Carrie. We know plenty about Carrie (a fascinating woman in her own right), but Columbia remains elusive. Her name, patriotic and a little daring, felt ahead of its time – the sort of bold choice modern parents might make. That curiosity sent me digging into her name, and then into her.

It turned into a detective story: following her footprints from Ohio to Iowa, a marriage in 1884, and, remarkably, a divorce she filed in 1885. Where Columbia’s trail leads me next is unknown, and that’s part of the pull.

Along the way, the broader picture for this article came into focus: Victorians balanced Marys and Williams with Sophronias, Permelias, Octavias, and Ulysseses. They used names shaped by literature, antiquity, family honor, and a dash of nerve. I hope this piece may nudge you to scan your own tree, spot the “out-of-place” name, and, before you know it, it’s midnight and you’re happily lost in the records.

Happy Reading & Researching,

Christine Skirbunt

Victorian names are like lace curtains: familiar at first glance (Mary, John, Elizabeth, William), but peek behind them and there can be a world of surprise. Parents in the 19th century didn’t just recycle family standards; they raided Shakespeare, swooned over poets, revived ancient Rome, honored generals, and occasionally christened a baby with something that sounded like a sermon. Below is a brisk tour of names that ranged from common, quirky, classical, literary, royal, and more. This quick guide covers both America and England from 1837 to 1901, with real people and receipts.

Everyday Victorians

Call “Mary!” or “John!” down a Victorian street and half the block might turn around. These names anchored both the U.S. and England for most of the century. Britain’s first official name list in 1904 still shows loyalists at the top (Boys: William, John, George, Thomas, James; Girls: Mary, Anne, Elizabeth, Sarah, Margaret). In the U.S., the earliest national rolls go back to 1880 and echo the British pattern (John, William, James, George, Charles; Mary, Anna, Emma, Elizabeth, Margaret).

But the Victorians began to branch out in the naming of their children. Beyond the “common” names, some required serious thought or literacy.

Shakespeare’s Children

The Victorians adored the Bard, and his heroines became fashionable first names:

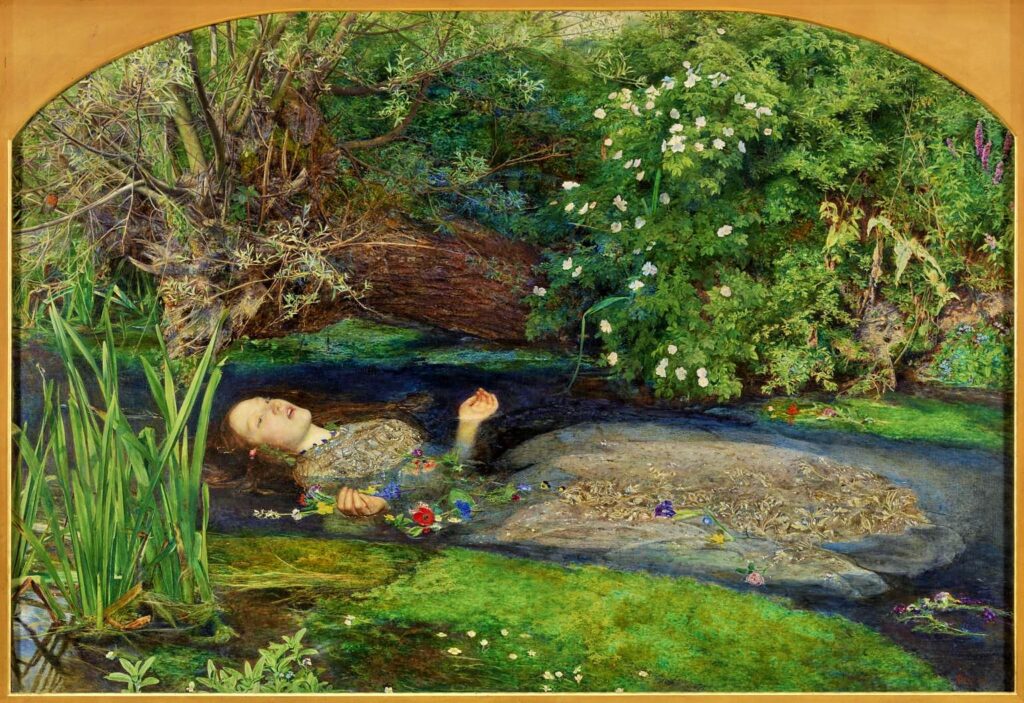

- Ophelia (“Helper”): tragic, lavish, and irresistibly Victorian thanks to John Everett Millais’s famous painting “Ophelia” (1851–52). It became an icon of the era’s Shakespeare revival.

- Beatrice (“Blessed”): from the quick-witted heroine in Much Ado About Nothing, a tasteful signal of bookishness.

- Cordelia (Unknown, but often “Heart/Daughter of the Sea” is the given meaning): loyalty and dignity from King Lear and his only daughter that truly cared for him.

- Rosalind (“Gentle Horse”) from As You Like It and Viola (“Violet Flower”) from Twelfth Night: both gentle, musical, and genteel.

- Imogen (“Maiden”): probably a printer’s error for “Innogen” in Cymbeline, but Victorians embraced the misspelling.

Even boys were given the Shakespeare treatment: Lysander (“Liberator”) from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Orlando (“Famous Throughout the Land”) via As You Like It turned up in the more literate households.

Real Life Cameo: American abolitionist and legal theorist Lysander Spooner (1808–1887) wore his Shakespeare/Greek hero name boldly in newspapers and pamphlets for decades.

When Poets Named the Nursery

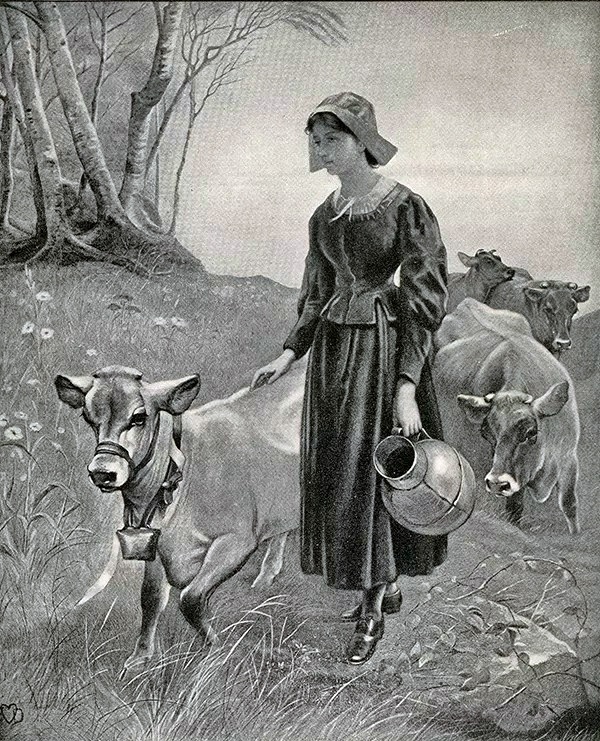

The print boom pushed fresh names into parlors. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1847 bestselling poem Evangeline helped turn Evangeline (“Bearer of Good News”) into a name with serious 19th-century overtures. Museums and the National Park Service still frame it as a Victorian cultural touchstone – both for the name and for putting the U.S. on the map for respectable poetry.

Arthurian revivalism from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King added Elaine (“Bright One”) and Enid (“Soul, Life”), while Gothic and Romantic tastes flirted with Edgar Allan Poe’s Lenore (Uncertain meaning, but usually “Light” is the accepted one), and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ianthe (“Violet Flower”) from Queen Mab rounded it out. These choices announced poetic tastes even if the baby’s world wasn’t all poetry.

Greco-Roman, But Make It Victorian

If a name sounded like it could be carved into marble, the Victorians were tempted to use it:

- Octavia/Octavius (“Eighth”): used whether or not the number fit.

- Aurelia (“Golden”): polished and elegant.

- Theodosia (“Gift of God”): used in Late Antiquity/Byzantium; in English it carries an elegant, old-world feel.

- Isadora (“Gift of Isis”).

- Cassius (Ancient Roman family name, the meaning today is unknown, but it is often paired with “Empty”). Victorians, however, only heard Rome.

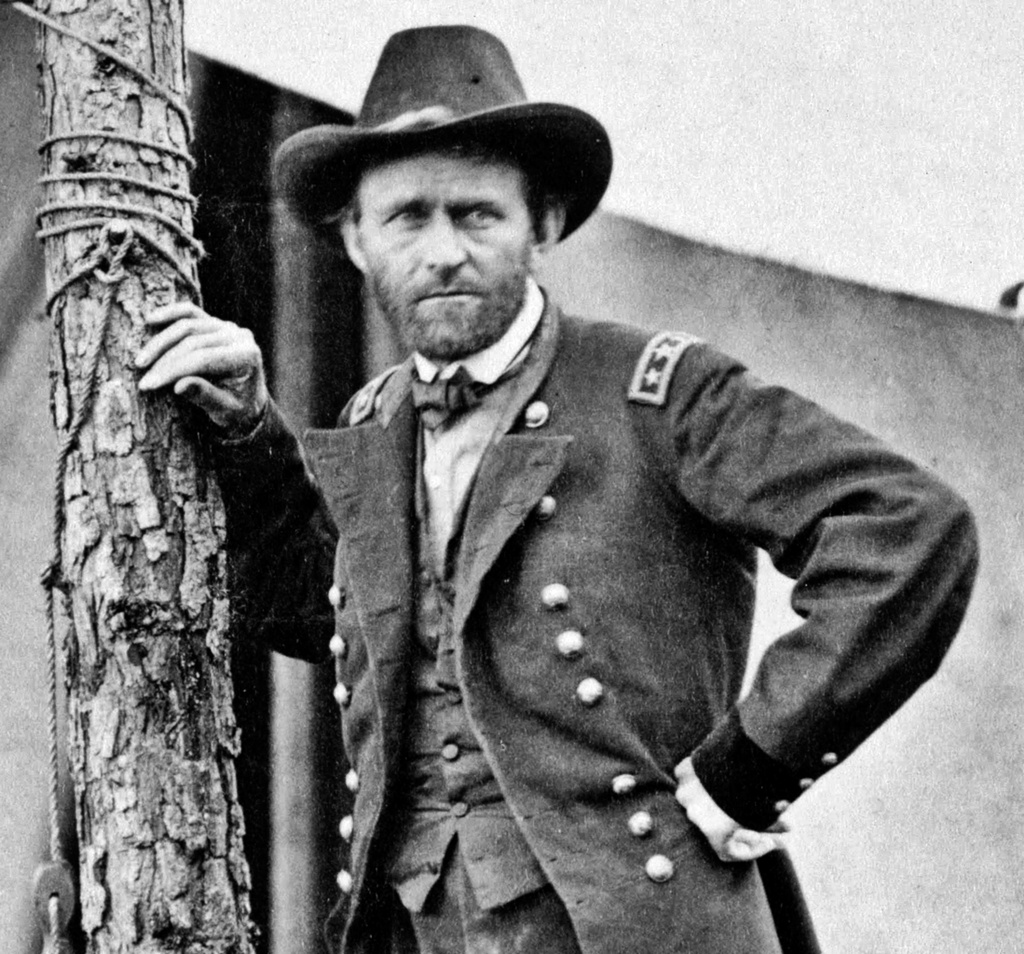

- Ulysses (Latin form of Odysseus, the exact meaning is uncertain but is often linked to “Wrathful”): permanently tied to U.S. general and president Ulysses S. Grant.

Real Life Cameos:

• Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) real name was changed in a West Point clerical mix-up from “Hiram Ulysses” to the “Ulysses S.” now known to history, thus enshrining the classical name into American headlines and history.

• Kentucky’s firebrand abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay (1810–1903) made a full Roman duo fashionable.

• Social reformer Octavia Hill (1838–1912), co-founder of the National Trust, wore a very classical first name that became quintessentially Victorian. Ideal for illustrating how “old Rome” met modern reform.

Birth Certificate Virtue

Victorian virtue-naming mellowed from earlier Puritan extremes, but the pews still echoed with Grace, Faith, Hope, Charity, Patience for girls and noble and meaning-adjacent Ernest/Ernest (“Serious, Steadfast”) for boys. Remnants of this older style lingered in New England family lines: Hopestill, Thankful, Experience, but they were curiosities by mid-century rather than trends.

Overly Royal and Wildly Popular

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s nursery became a baby name trendsetter, especially in Britain:

- Albert (“Nobly Bright”): seemingly everywhere to honor the Prince Consort.

- Victoria (“Victory”): patriotic and queenly to honor the Queen.

- Alice (“Noble Type”): very popular after Princess Alice’s birth (1843).

- Beatrice (“Blessed/Bringer of Joy”): the queen’s youngest daughter (1857).

- Arthur (meaning debated but often interpreted as “Bear”): boosted by Prince Arthur (1850) and the ongoing broader Arthurian revival theme.

By the 1870s, parish registers brimmed with Alberts, Alices, Arthurs, Beatrices. British Victorians simply could not get enough of royal names!

Nature, Flowers, and Jewels

As the century progressed, girls’ names blossomed, quite literally: Lily, Daisy, Violet, Ivy, and Rose became a sensation, while jewels like Pearl and Ruby joined the bouquet. U.S. decade lists confirm the late-century presence of these sweet florals and gems.

Boy’s names didn’t take on many florals, but Basil (“Royal and Kingly”) and Forrest (“Keeper of the Forest”) fit the era’s nature mood.

Surnames As First Names

A 19th-century habit that has never really ended was turning notable surnames into first names. In Britain, think Sidney, Howard, Stanley, Clifford, Spencer; and in the U.S., add the patriotic roll: Grant, Cleveland, Lafayette, Washington, Franklin. Family surnames as first names crop up in both countries in probate, parish, and census entries throughout the era.

The Quirky Side

Beyond court fashions, classics, and sermons, some Victorians reached for names that were uncommon local, or just delightfully odd.

- Columbia (“U.S. Personification”): used as a given name, it references America as the Land of Columbus. Not to be confused with Colombia, the country in South America.

- Sophronia (“Self-Controlled”): Most notably, Sophronia Bucklin (1828–1902), was a Civil War nurse and author of In Hospital and Camp (1869).

- Permelia (Of obscure origin, possibly a version of “Amelia”): Permelia Redmon Wheeler’s mid-19th-century portrait resides at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

- Tryphena (New Testament “Dainty and Delicate”): Tryphena Sparks (1851–1890), a headteacher and noted as being her poet-cousin, Thomas Hardy’s lover.

- Zillah (“Shade or Shadow”): Hebrew and from Genesis in the Bible.

- America, Missouri, Virginia (Place-Proud Names): Especially popular in America, with different place names cropping up regularly in registers and newspapers in the 19th century.

Real Life Cameos:

• Sophronia Bucklin was a Civil War nurse and author. She gave a face (and memoir) to a name many modern readers have never met.

•If Permelia Redmon Wheeler’s name may look straight out of a Victorian novel, it’s because she very nearly is: she was the famous sitter for an 1840s portrait by her sister, the folk and travelling painter, Lucinda Redmon Orear.

These quirky names aren’t inventions for fiction: they’re on real certificates, in museum collections, and in biographies. Sophronia wrote from battlefield wards and Permelia stares right back at us from a gilt frame.

Closing Chord

From the devotional calm of Mary and John, to the old-book-scented love and loss of Ophelia and Evangeline, to the marble-bright classicism of Octavia and Cassius, Victorian naming was far from monochrome – it was a spectrum. Whether the goal was virtue, culture, heritage, or a bit of drama, Victorian parents found ways to be traditional and original. Their choices still ring with story and usage today.

References:

“Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie.” https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/evangeline.htm

“SSA: Top Names of the 1880s.” https://www.ssa.gov/oact/babynames/decades/names1880s.html

“Top 100 baby names in England and Wales: 1904-2024.” https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/datasets/babynamesenglandandwalestop100babynameshistoricaldata

“Ulysses S. Grant.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulysses_S._Grant

“Virtue Names.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtue_name

Images:

- Columbia (L) and Carrie (R) Glass: Author’s Collection

- Family Bible Births of Columbia Glass (1866) and Carrie Glass (1878): Author’s Collection

- Evangeline; Poem by Longfellow: https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/evangeline.htm

- John Everett Millais’s “Ophelia” (1851–52)

- Octavia Hill, 1882: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Octavia_hill.jpg

- Permelia Redmon Wheeler, 1845: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lucinda_Redmon_Orear_-_Permelia_Redmon_Wheeler_(1816-1881)_-_190-1951_-_Saint_Louis_Art_Museum.jpg

- Overused Royal Names: https://chatgpt.com/

- Tryphena Sparks: https://www.amazon.com/Thomas-Hardy-Andrew-Norman-author/dp/0857043013

- Ulysses S. Grant at Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grant_crop_of_Cold_Harbor_photo.png

Further Reading:

“Lysander Spooner.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lysander_Spooner

“Octavia Hill.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octavia_Hill

“SSA: Top Names of the 1880s.” https://www.ssa.gov/oact/babynames/decades/names1880s.html

“Top 100 baby names in England and Wales: 1904-2024.” https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/datasets/babynamesenglandandwalestop100babynameshistoricaldata

“Tryphena Sparks.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tryphena_Sparks

Leave A Comment