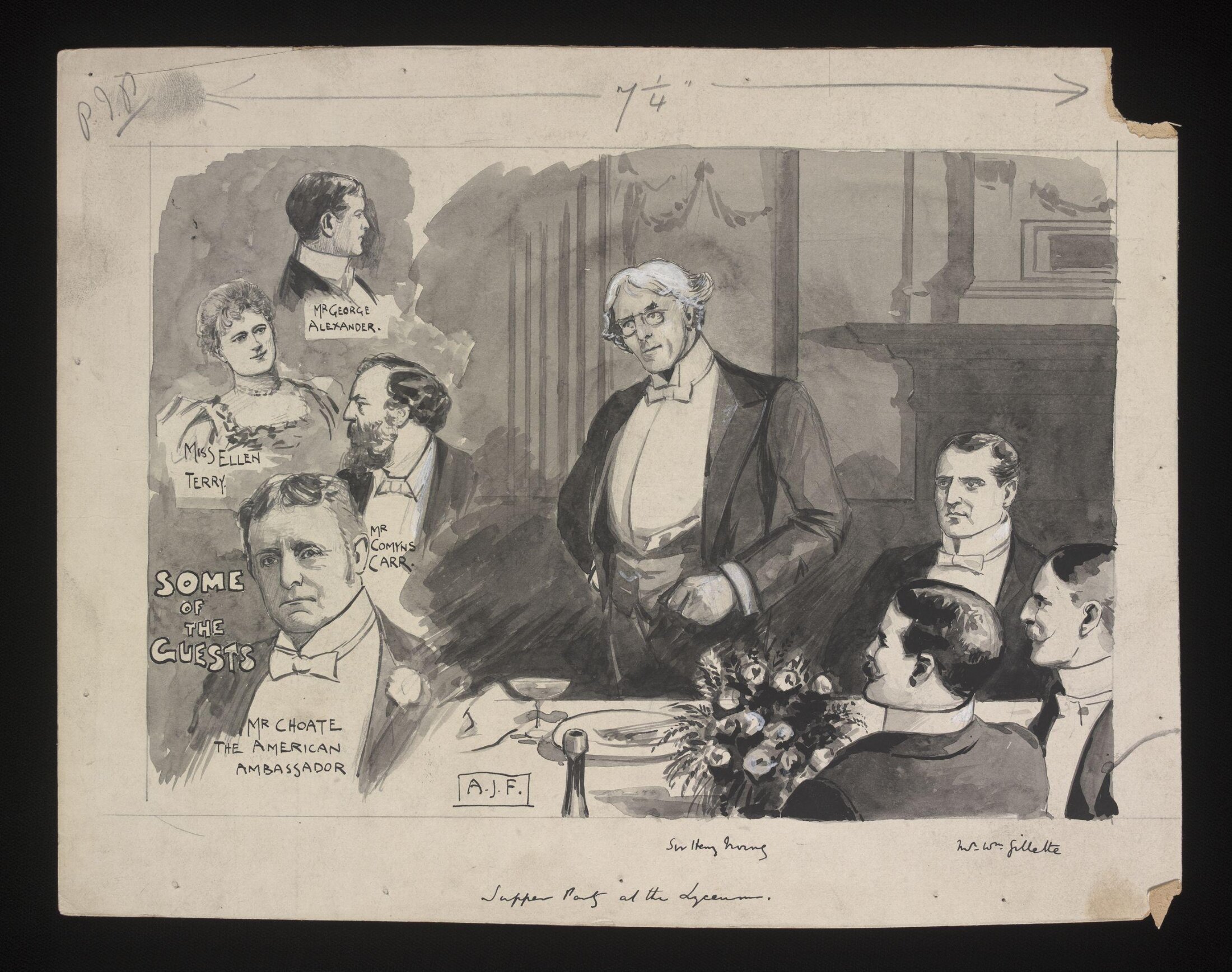

Motions pictures were invented over 130 years ago and remain one of the most popular forms of entertainment. But the concept of a visual experience to transport audiences to a new place wasn’t new, even in the 1880s. In the 18th century artists with remarkable vision created visual delights that would allow huge audiences to escape reality and enjoy magical new surroundings. Let’s take a look at panoramas.

Colosseum panoramas

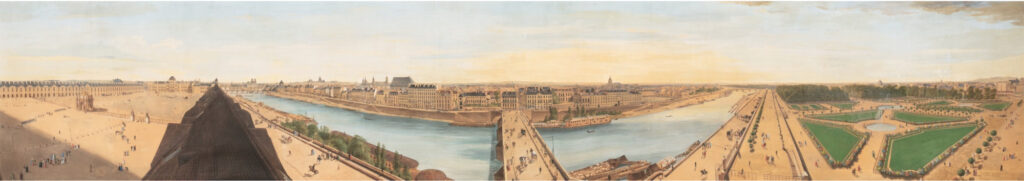

The word “panorama,” though common today, was concocted by the artist who would also hold the first patent for the concept. Scottish painter Robert Baker devised the term when he unveiled what is largely considered to be the panorama that started the century-long trend. Created using the English word “pan,” meaning “view” and the Greek word “horama” meaning “all,” Baker sought to create a visual experience that would transport viewers to a foreign place.

Baker’s first panorama was debuted in Leicester Square in 1791 and depicted the sights of Edinburgh. It was a time of great curiosity about the world, making this type of experience ideal for mass consumption. Says Sotheby’s:

“The times were conducive to this kind of enterprise. The development of tourism, and the curiosity of the inhabitants of London, Paris or Berlin were a driving force for new attractions which greatly benefited the panorama. It rapidly became one of the century’s major sources of entertainment across all of Europe. Its promoters exhibited these fragile and imposing works before sending them off to the great capital cities of Europe. The frequent handling of these delicate pieces exposed them to deterioration which explains why so few remain today. It was only with the advent of cinema that the panorama lost its importance, before disappearing completely at the beginning of the 20th century.”

The attraction was so popular that similar “shows” would begin popping up all around Europe, becoming more and more elaborate. They would sometimes involve ticket holders walking through a tunnel before entering a 360 view of an entirely new scene. It was so disorienting that some people even become sick, similar to what is experienced at the Grand Canyon still today.

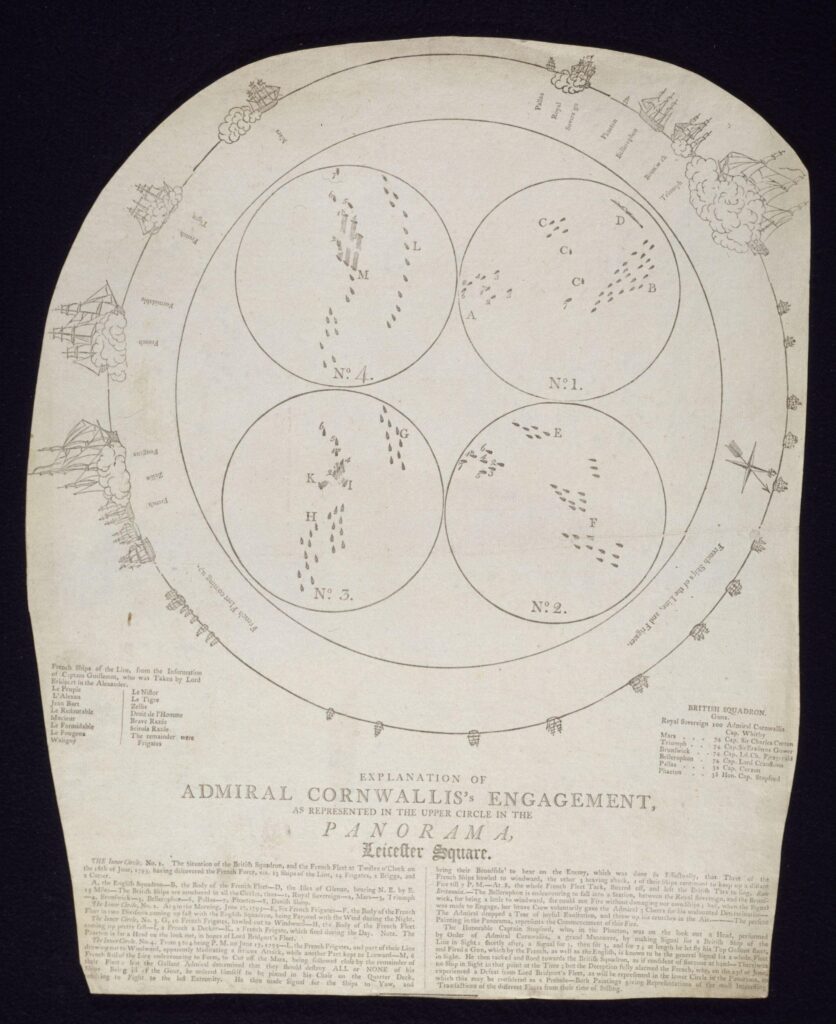

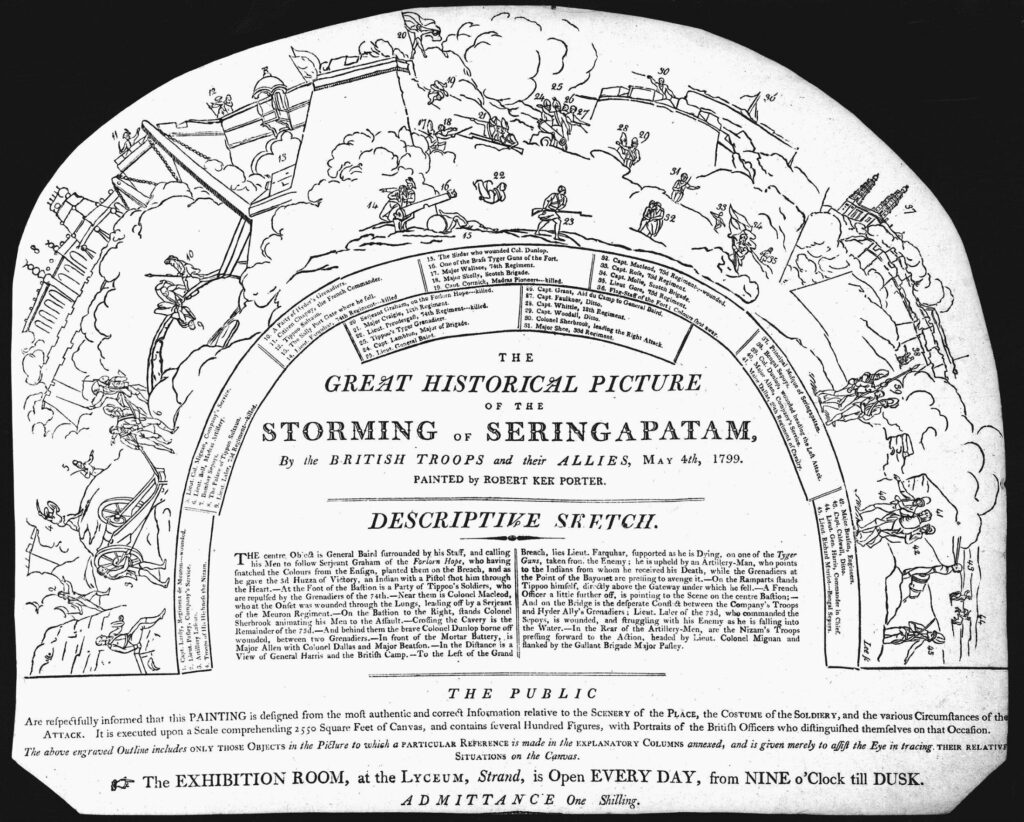

The coliseum panoramas were so massive and detailed that maps were often given to the audience. Two examples are below, followed by some photographs of surviving panoramas.

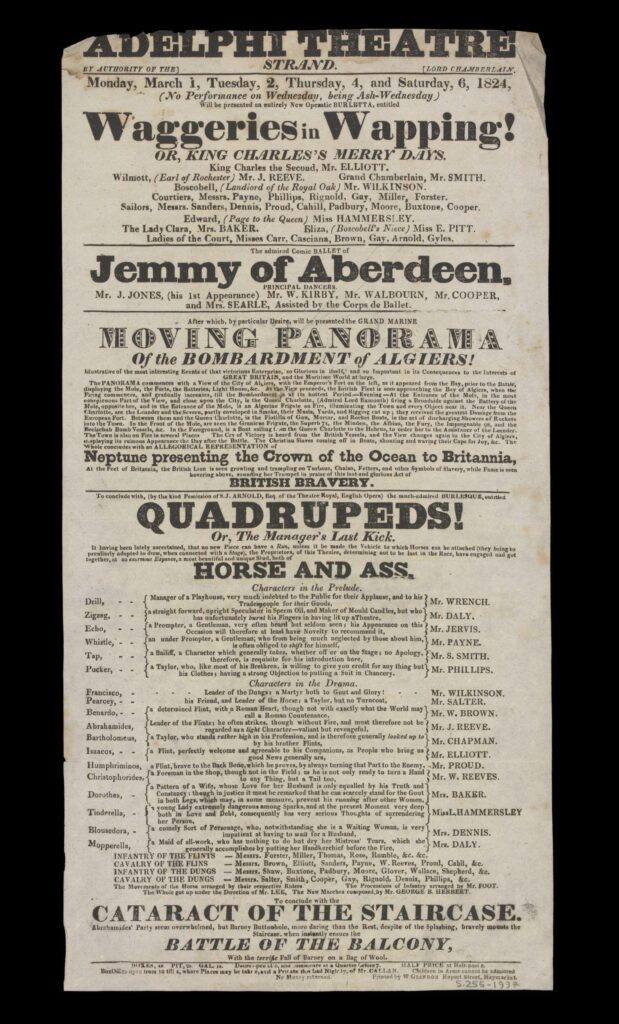

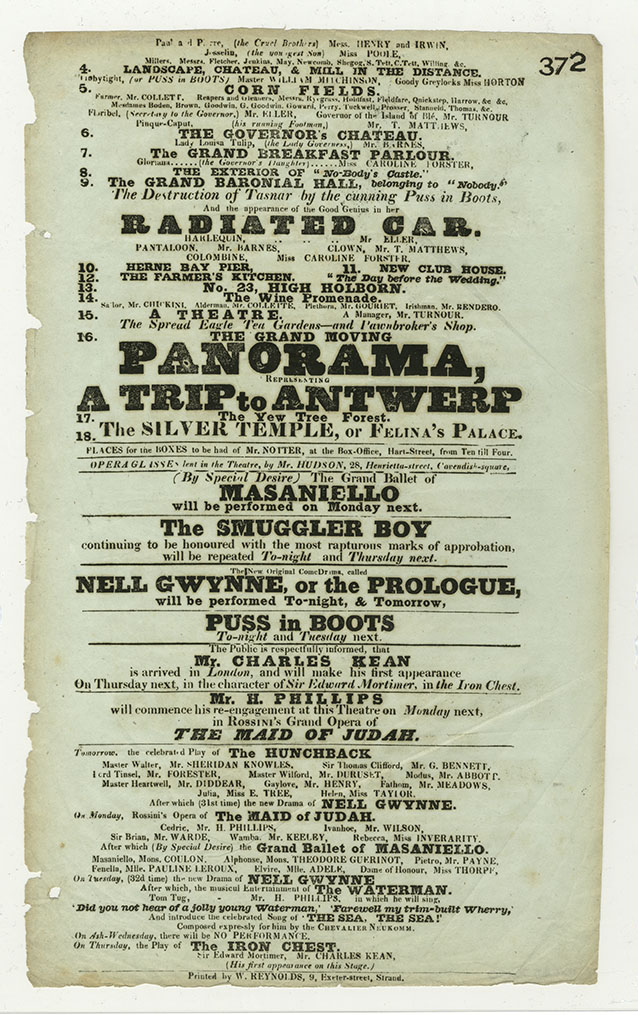

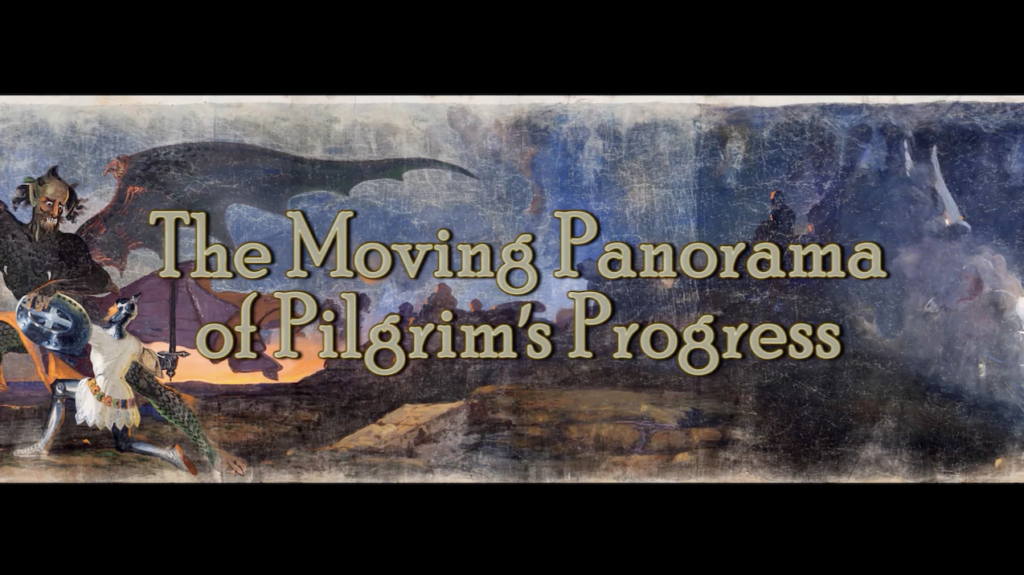

Moving panoramas

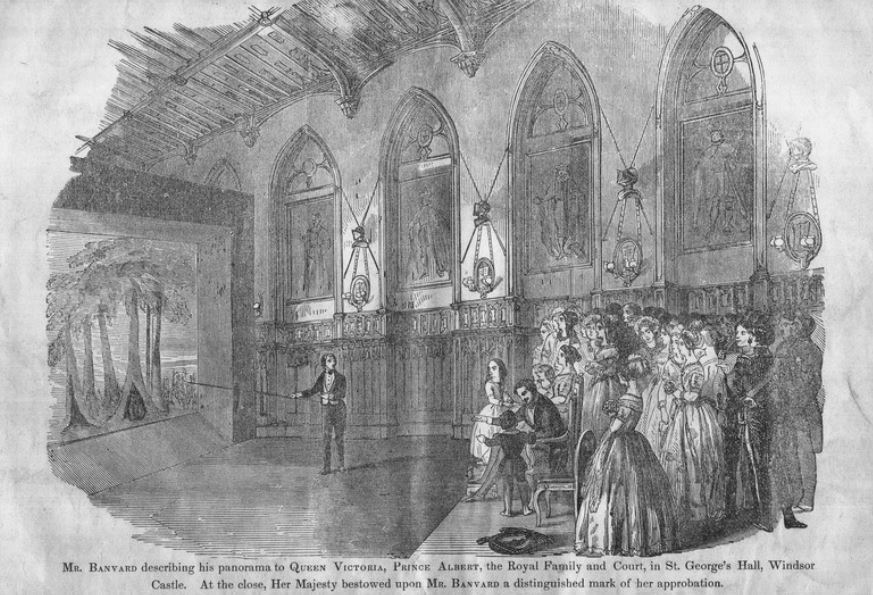

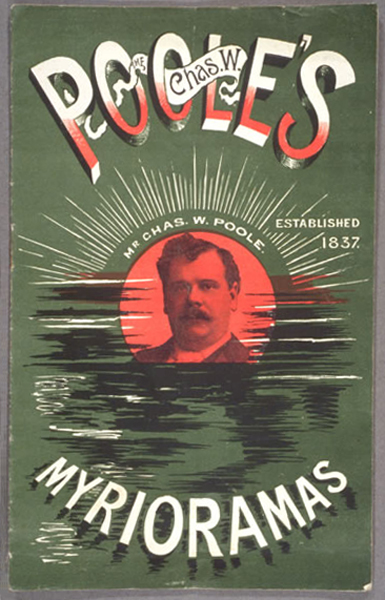

The popularity of the large-scale panorama experience led to the reemergence of the moving panorama, often considered to be the inspiration for the eventual invention of the motion picture. The moving panorama took the concept of using large-scale imagery to transport viewers to a new place, only by sitting in front of a moving image, this time accompanied by lighting, music, and narration. In The Moving Panorama, a Forgotten Mass Medium of the 19th Century Erkki Huhtamo gives a great history of this theater experience and explains the device:

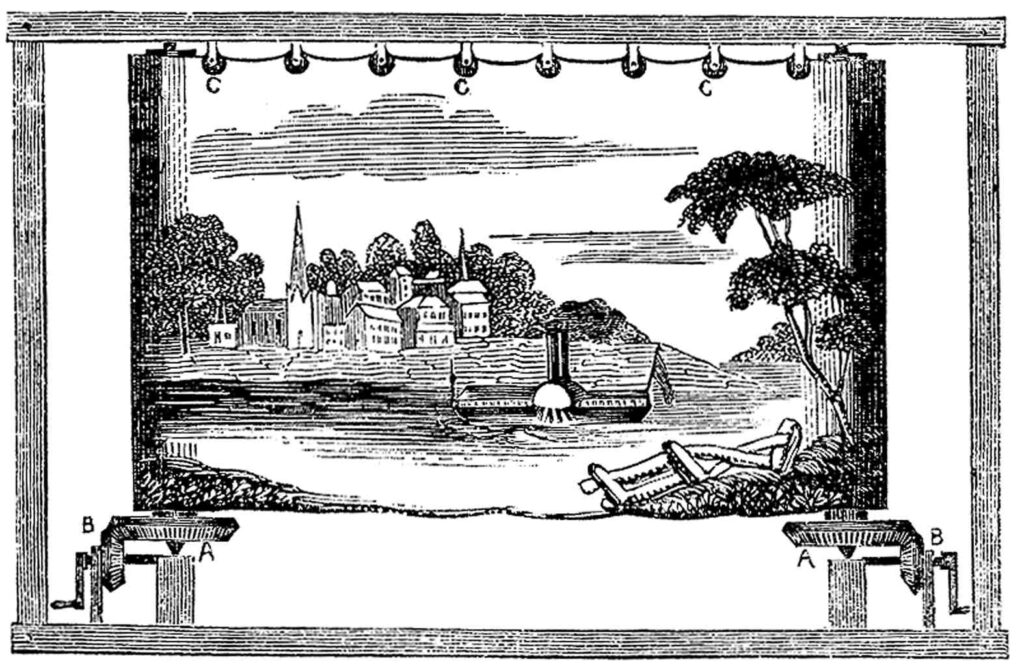

“Although the constitution of the moving panorama as an apparatus was never uniform, evolving with time, its basic elements could tentatively be described as follows. The audience members, instead of being surrounded by the image, were seated in front of it as in a theater or a lecture hall (or, anachronistically, a cinema). Facing them was a “window”, a square opening visible through a proscenium arch. A long strip of canvas with painted images was moved horizontally across this stage opening from one vertical roller to another by means of a mechanical cranking mechanism. The images often formed more or less continuous “panoramic” scenes, but the roll could also consist of distinct “views”. The rollers, as well as the cranking mechanism and the instruments for creating sound effects and music, were hidden from the audience’s view. A lecturer usually stood next to the canvas, explaining it to the audience as it moved along. Instead of offering a static spatial illusion, such shows presented changing scenery and combinations of images, speech and sounds.”

Image source: BDCMuseum.org

The moving panorama was particularly popular in America, with one of the earliest being an elaborate portrayal of Pilgrim’s Progress debuting in 1850. It is remarkably one of the only surviving moving panoramas in existence today and is housed at the Saco Museum. Learn more in the video below.

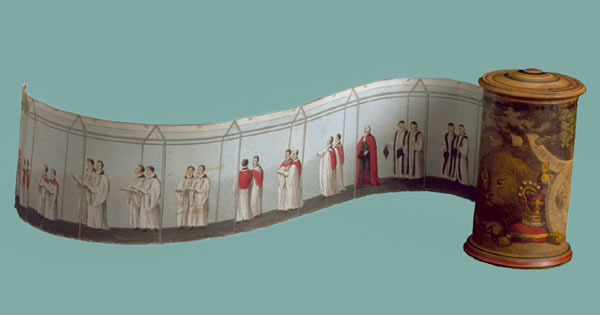

Toy panoramas

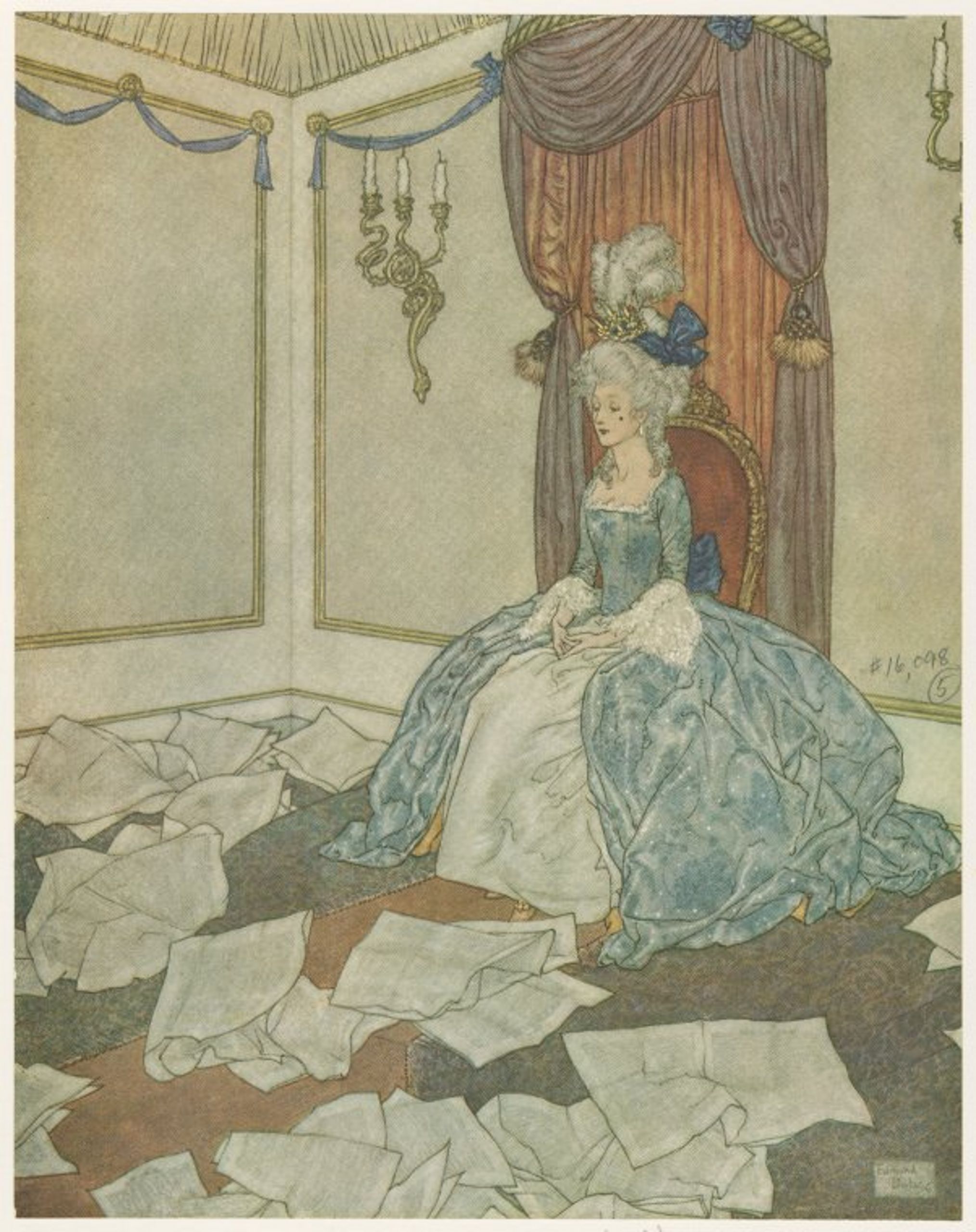

My favorite! Reminding me of Fisher Price televisions and radios of my 1980s youth, the craze around this form of entertainment was quickly adapted for children in the form of toy panoramas. Their mass production was short lived, being primarily a Regency item. This surprises me given the popularity of various visuals in the Victorian era. Perhaps it was a matter of rapid industrialization and new products emerging so often.

Whatever the case, they were advanced and charming. I have seen two types: one that mimicked a moving panorama with a long scroll wrapped around two small polls like the one below.

The other type was meant to replicate the experience of watching a moving panorama from the audience, with smaller sections being wound through a small box that framed the moving image. Two examples are below.

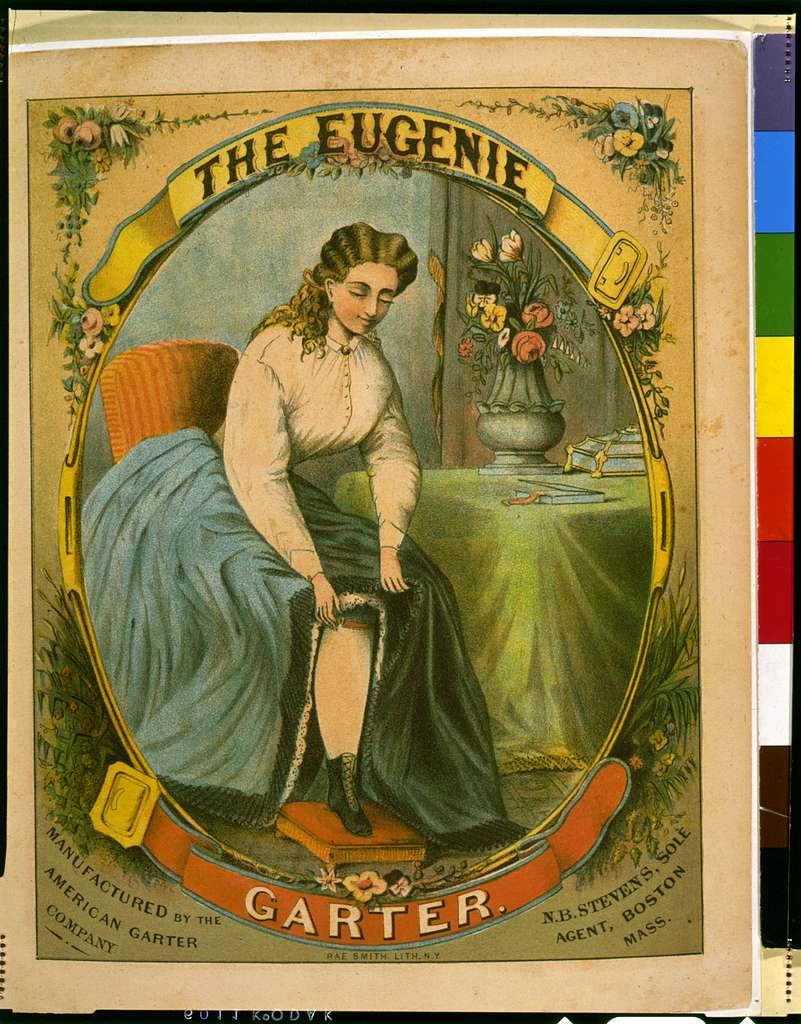

Readers will be interested to know that toy panoramas were briefly used as perks for both men and women renewing fashion magazine subscriptions. I am currently researching these artifacts and hope to write a future post on these specifically.

Interest in panoramas would naturally decline in the 1880s with the emergence of photography and then the motion picture. I think that they were ingenious enough and that enough time has passed, however, for a comeback. I could see there being a strong interest in the artisanship and in honoring the various forms of entertainment that paved the way for what we enjoy today.

What do you think? Would you enjoy a panoramic experience similar to those of the 1800s?

More entertainment from the past:

Before selfies, there were friendship books

Leave A Comment