Author: Christine Skirbunt

When autumn’s chill tiptoes in, leaves turning russet, morning air sharpening, many of us instinctively reach for a sweater. That cozy ritual feels so natural. But it is worth remembering that there was a time when knitwear was considered purely utilitarian, and women’s autumn wardrobes were dominated by layers of structured fabrics and corsetry. The quiet revolution that brought knitwear into mainstream fashion grew from the patriotic labor of wartime knitting circles in the 1910s to the rise of soft jersey in high fashion during the elegant 1920s. Today’s inviting fall knits are more than seasonal staples: they carry a legacy of rebellion and freedom.

Autumn Fashion Before Knitwear

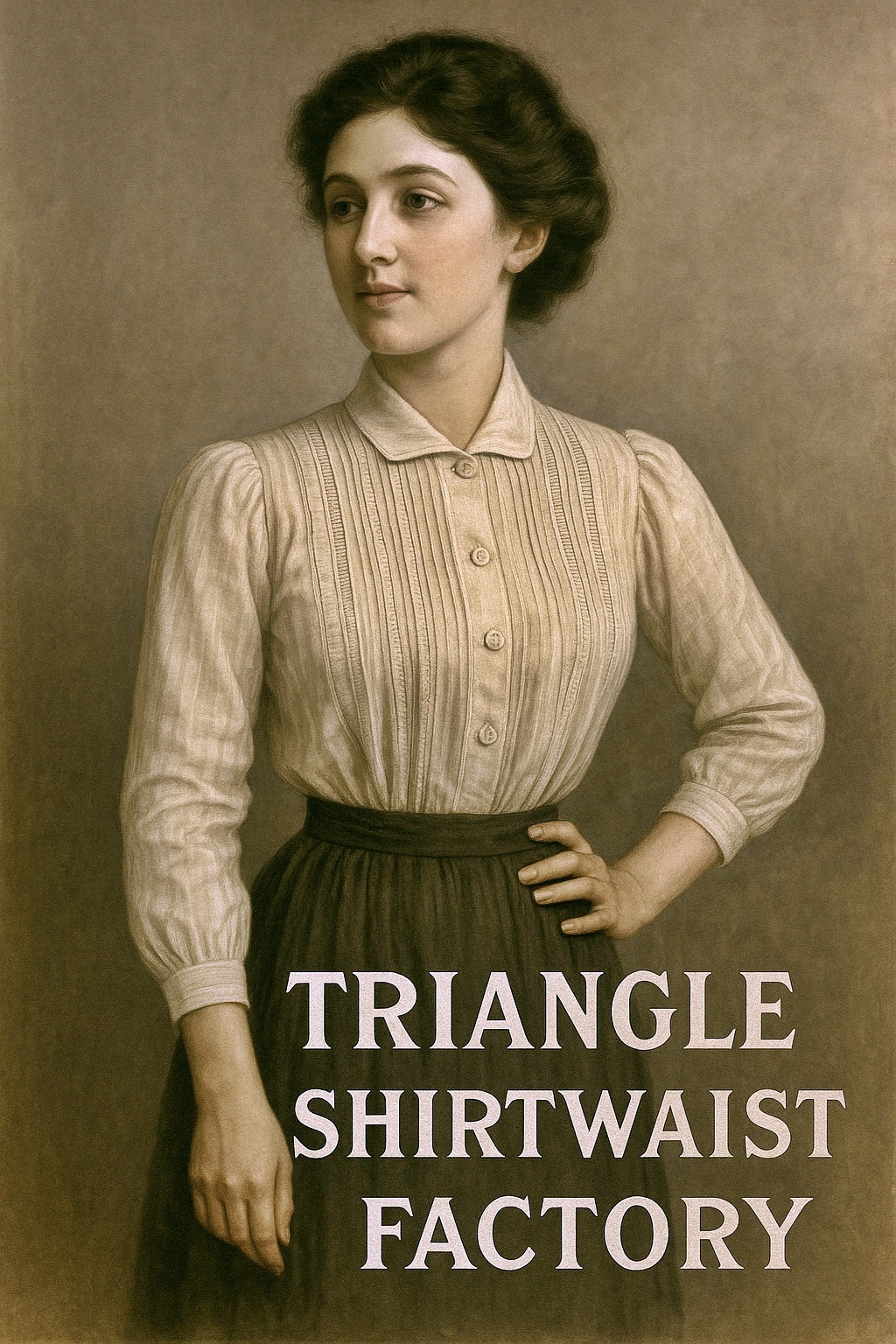

During much of the 19th century, women’s autumn wardrobes were built on structure: corsets, bustles, layered skirts, and outerwear tailored with precision and stiffness. The fabrics were wool, brocade, taffeta, and twill. They were heavy and elegant but lacked stretch or adaptability. To go outdoors in the fall meant cloaking oneself in mantles or fur-lined coats.

Knitwear at the time was nearly invisible in women’s fashion. It existed mainly in the domestic sphere such as socks, shawls, and baby clothes. It was handmade, humble, and practical, certainly not a fashion statement. The idea of wearing knitted garments as outerwear was unthinkable in most social circles.

The exception to this rule was that while fashionable women in elite and urban circles were expected to conform to rigid, structured silhouettes, there were pockets of exception in rural communities where working-class women, domestic servants, and fisherwomen were more likely to wear practical knitted items for warmth and durability. For example, women in coastal regions wore hand-knitted shawls, mitts, and gansey-style sweaters while mending nets or tending boats. These garments were made from dense wool that repelled water and offered mobility. But these women were not seen as fashionable. They wore “necessity wear,” that was confined to labor or home use. In polite society, a woman wearing a sweater to town would risk being seen as underdressed, even indecent.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that the functionality and comfort of such garments began to infiltrate respectable, visible fashion for middle- and upper-class women. This made the demand of the 1910s and the innovations of the 1920s even more liberating.

World War I Sets the Stage for the Knitted Revolution

The First World War did more than alter global geopolitics: it transformed domestic life and reshaped the cultural meaning of “women’s work.”

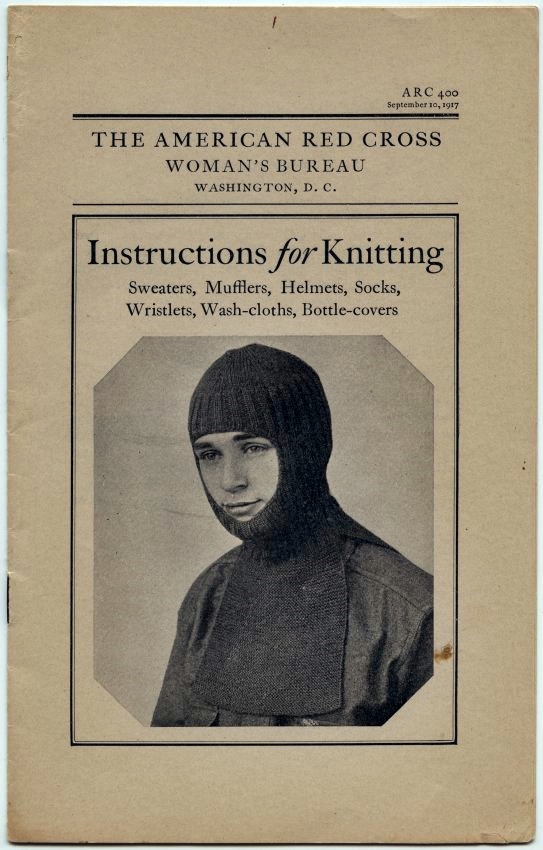

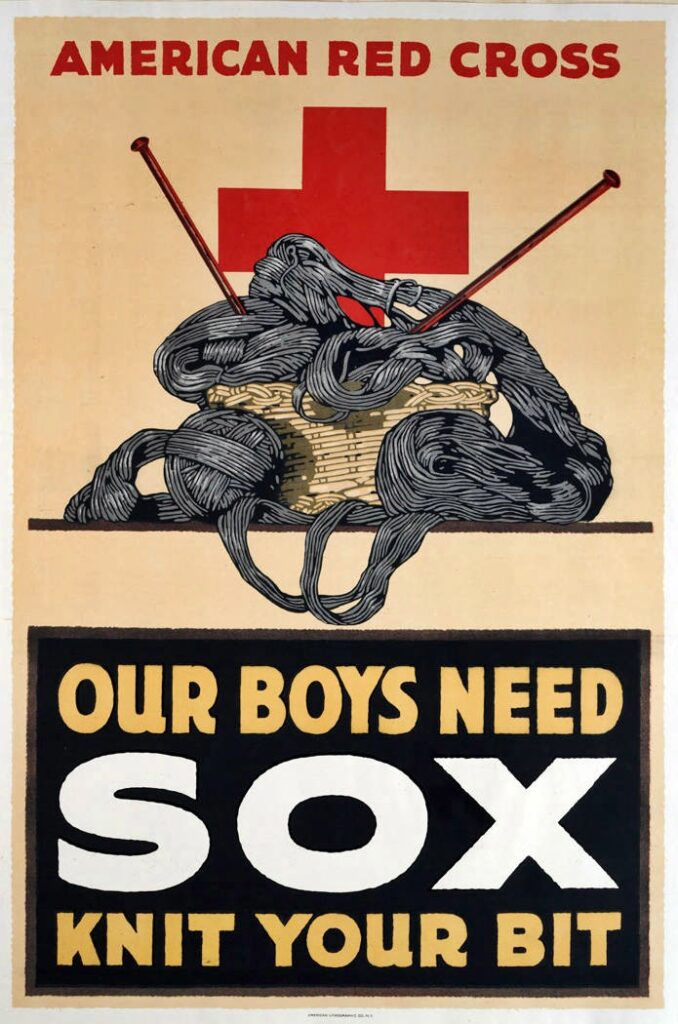

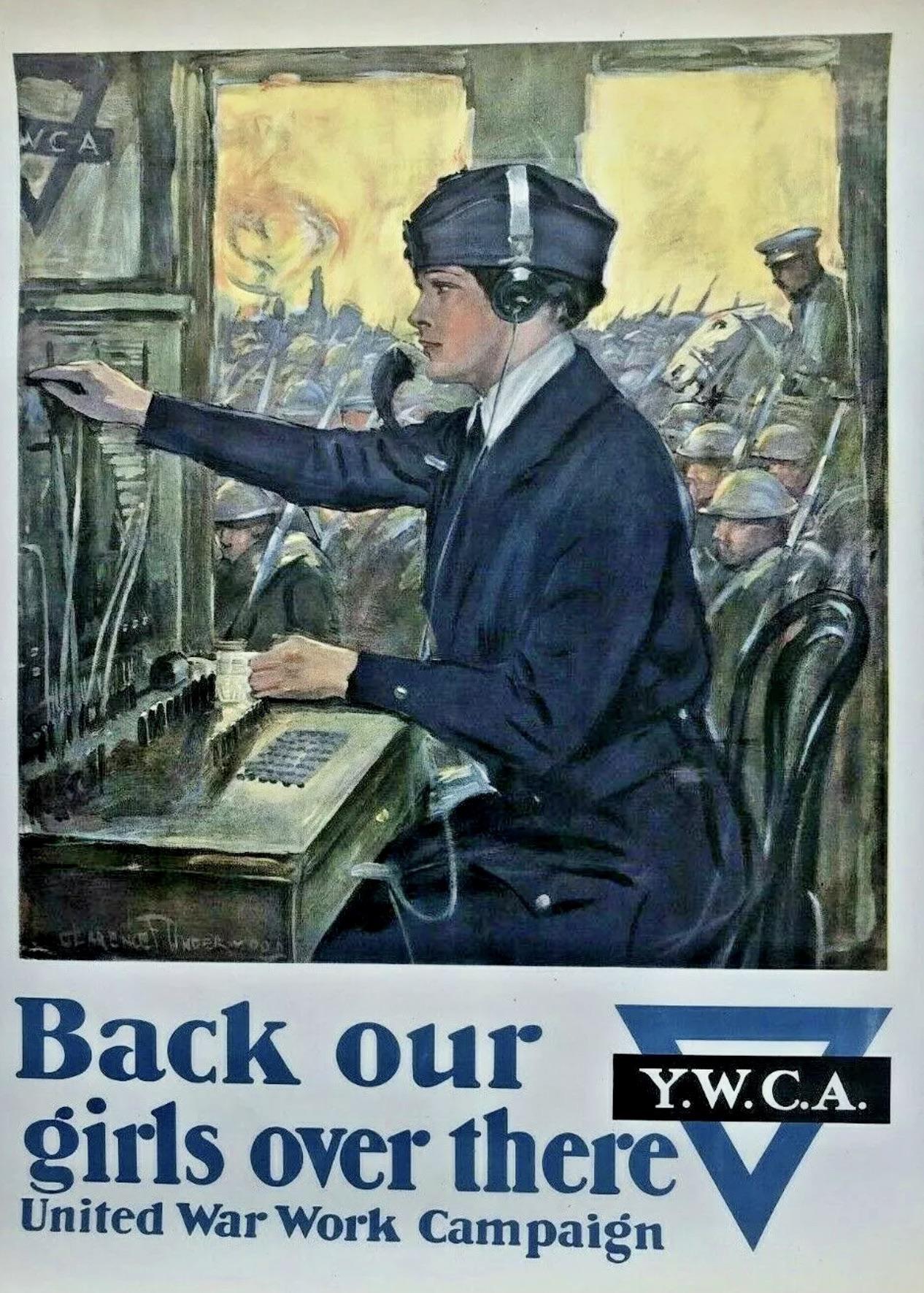

As early as 1914 in Europe, and by 1917 in the United States, knitting became one of the most visible ways women could contribute to the war effort from home. Soldiers in trenches needed wool socks, scarves, gloves, vests, and balaclavas to survive cold, wet conditions. In response, the American Red Cross and its European counterparts issued a resounding call: women must pick up their needles and knit for the troops!

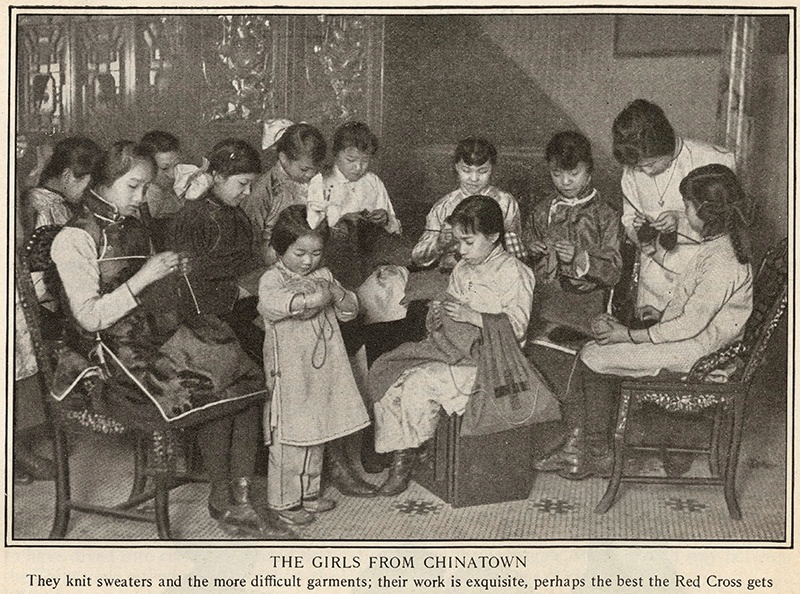

These appeals were highly organized and widespread. The American Red Cross, for example, distributed millions of free patterns and provided standardized materials when possible. Government agencies and private charities also joined in, creating knitting circles in homes, churches, and schools. Some cities held “knit-ins” or public knitting demonstrations to recruit more women and encourage patriotism. This created a generation of skilled women knitters. But knitting was no longer a mere hobby but now a major contribution to a national cause. The knitting needles became a symbol of patriotic labor, and the soft, stretchy garments they produced began to be seen in a new light: meaningful, versatile, and deeply connected to female agency.

It wasn’t just women, either. Men were also encouraged to knit, schoolchildren were taught how the skill in classrooms, and many elderly or disabled individuals contributed. Though knitting was traditionally framed as “women’s work,” many others took it up during wartime as a sign of support. Even injured soldiers began knitting to pass the time and help make garments for their comrades.

This push for knitted goods came in large part from male-dominated institutions. Military supply officers and medical personnel on the frontlines reported high rates of trench foot, frostbite, and illness caused by damp conditions and lack of dry socks. These reports made their way back to civilian leadership, and knitting quickly became a national concern.

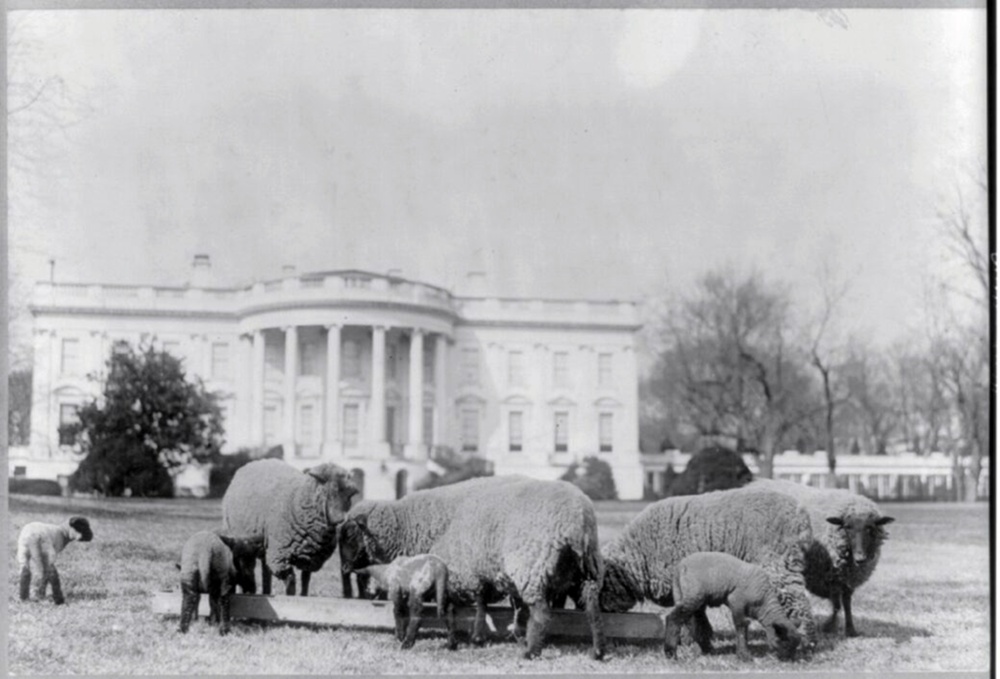

It became so important that First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson supported the knitting campaign during the presidency of her husband, Woodrow Wilson. An unexpected chapter of American wartime history is that the White House managed a flock of up to forty-eight sheep on its grounds to maintain the lawn and produce wool for auction. Over $50,000 was fundraised by the selling of the White House Wool and donated to the American Red Cross. By 2025 standards, that is the equivalent of over one million dollars!

With the President and First Lady behind the cause, posters urged women to “Knit Your Bit” and men’s wartime needs lent knitting an air of civic importance. American volunteers used forty-five million pounds of wool and the American Red Cross reported that over fifteen million knitted items had been produced. Volunteers dedicated two million hours, or approximately 230 years’ worth of labor, in the 18 months the U.S. was at war.

Knitting Becomes Empowerment

Through war-knitting, women experienced a profound sense of purpose, unity, and public involvement. It was a rare moment where domestic labor was recast as civic engagement, and women were praised not just for keeping the home but for helping to win a war.

This gave knitting cultural staying power even after the war. Women who had learned new techniques or joined communal circles kept knitting, experimenting with colorwork, cables, and fashionable silhouettes. They had touched something powerful and they didn’t let it go when peace returned.

As a result, by the time the 1920s brought about looser fashion norms, a ready-made faculty of skilled, confident knitters already existed. What was once a duty became a fashion revolution.

Chanel, Jersey, and the Birth of the Modern Sweater

Few names loom larger in the history of knitwear than Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel. In 1916, she shocked the fashion world by using jersey – a fabric traditionally reserved, up until then, for men’s underwear and workwear – for stylish women’s dresses and suits.

Jersey’s properties were revolutionary: it was soft, it stretched, it draped naturally, and it didn’t require boning or corsets underneath. Chanel used these qualities to create garments that followed the body without restricting it. She helped usher in a new silhouette: slim, androgynous, often drop-waisted, and entirely comfortable.

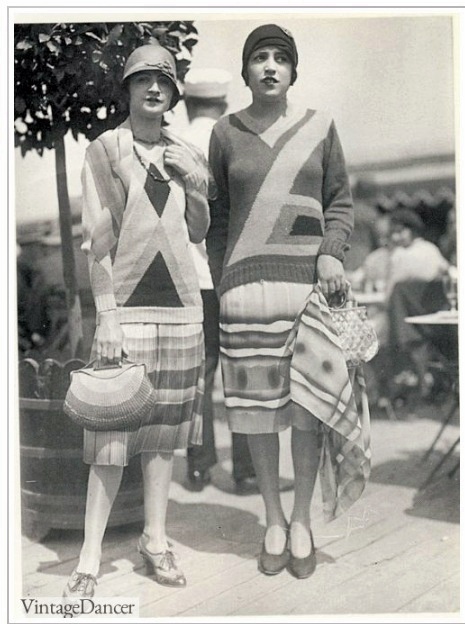

Sweaters followed close behind. No longer confined to fisherwomen or men’s rowing clubs, the pullover, cardigan, and sweater-coat were suddenly chic among all classes of women and seen everywhere.

The popularity of the “college girl” look only added fuel to the fire. Young women at universities wore oversized cardigans, V-neck pullovers, and letterman sweaters. These were previously symbols of masculine academia but now with a woman’s flair. Some of these articles of clothing were nearly indistinguishable from men’s styles and only simply adjusted for fit and color.

The New Look of Autumn

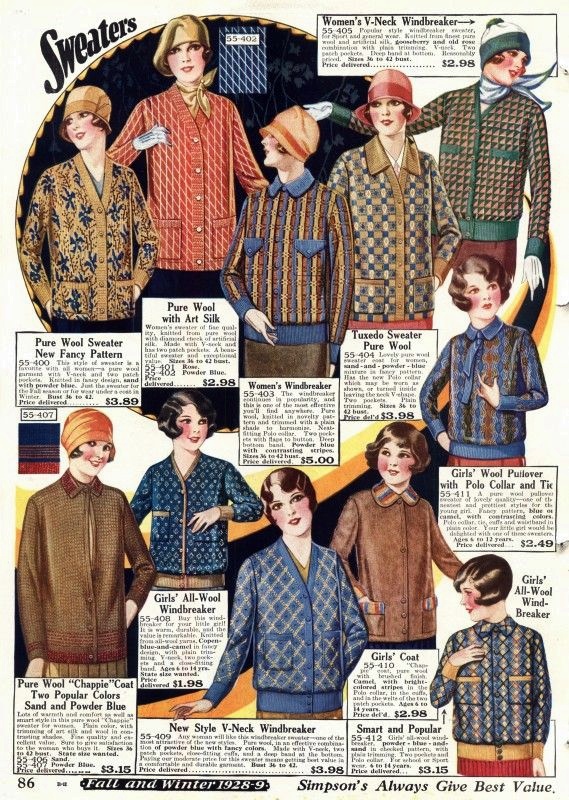

1920s knitwear was perfectly suited for the changing seasons. Sweaters were layered over crisp cotton blouses or silk chemises, often paired with knee-length skirts, thick hosiery, and low-heeled shoes or oxfords.

Fall colors were everywhere: deep maroons, hunter greens, mustard yellows, and rust oranges. Sweaters might feature stripes or contrasting trim or be so bold as to add Art Deco or Native American patterns. It was also about texture – ribbing, cable, and soft drape – that gave sweaters visual interest.

Accessories followed suit: the ever-popular knitted cloche hat, scarves, mittens, and even handbags added seasonal warmth. Knitting had become more than a cozy sweater: it was now fashionable, versatile, and adaptable to almost any setting, especially in autumn’s unpredictable weather. Sweaters, especially, became symbolic of ease. They were democratic, affordable, and accessible, whether made by hand or purchased ready-to-wear. They democratized fashion with fewer layers, fewer class distinctions, and, finally, fewer rules. In a world where women had just earned the vote and gained traction in universities and workspaces, sweaters were almost a symbolic soft armor for modern life.

Wearing knitwear in the 1920s meant more than embracing comfort. It was a visual rebellion against previous generations’ expectations.

The Enduring Legacy of the 1920s Knitwear Revolution

Today, the sweater is one of the most universally loved autumn garments, but we owe much of its popularity and symbolism to the demand of the battle-scarred 1910s and the novel innovations of the 1920s.

Knitwear continued to evolve through the 1930s–50s, from form-fitting sweater sets to WWII-era utility knits. Designers like Goldworm in America and Olga di Grésy in Europe elevated knitwear into the realm of luxury fashion, pushing its techniques and prestige even further. These women and brands helped transform knitwear from simple function to high art, ensuring its place on runways, in ready-to-wear shops, and in households around the world.

Even today, runway designers revisit 1920s styles: drop-waisted dresses, knit vests, oversized collegiate cardigans, and sporty sweater sets all return with cyclical charm. Designers like Chanel, Chloé, and Miu Miu (to name just a few), regularly feature richly textured knits in their fall collections. At the same time, department store brands like H&M, Banana Republic, and The Gap fill their shelves each autumn with cozy cardigans, soft pullovers, and sweater dresses that carry unmistakable echoes of their 1920s foremothers.

This dual presence on the catwalk and the clearance rack is the ultimate testament to knitwear’s staying power. It remains both luxurious and accessible, tailored, and oversized, elegant and every day. Whether it’s a Union Jack sweater worn by supermodel Kate Moss or a $25 cardigan from the mall, each knit carries the history of the 1920s revolution: comfort, ease, movement, and the audacity to redefine what women could wear.

So, when fall comes around and you reach for your favorite sweater, remember that you’re not just dressing for the weather: you’re honoring a century of bold women who redefined fashion, one stitch at a time.

References:

“Goldworm.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldworm

“Knitting the Nation.” https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/knitting-nation

“Olga di Grésy.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olga_di_Gresy

“The Unlikely Knitters of World War I.” https://pieceworkmagazine.com/the-unlikely-knitters-of-world-war-i

“The White House Lawn Was Once Covered With Grazing Sheep.” https://dcist.com/story/20/03/06/the-white-house-lawn-was-once-covered-with-grazing-sheep

Images:

- 1928 Sweater Advert: https://retrorover-vintagedogs.blogspot.com/2014/09/college-fashions-of-1920s.html

- Coco Chanel: https://www.vogue.com/article/1920s-fashion-history-lesson

- Coco Chanel’s Jersey Twinsets: https://fashiontextilemuseumblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/11/exhibition-archives-knitwear-chanel-to-westwood

- Collegiate Sweaters Basketball Team: https://retrorover-vintagedogs.blogspot.com/2014/09/college-fashions-of-1920s.html

- Collegiate Sweaters On Campus: https://chatgpt.com/

- Knit Dresses & Handbags: https://vintagedancer.com/1920s/ladies-1920s-sweaters

- Guide to Knitting: https://collections.theworldwar.org/argus/final/Portal/Default.aspx?component=AAAS&record=6eec2929-de90-427f-91aa-6911f1d1a1da

- Knitting Circle Chinatown: https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/knitting-nation

- Knitting Circle Home: https://chatgpt.com/

- Knitting Circle Whittier School, Hampton, VA: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/when-knitting-was-a-patriotic-duty-wwi-homefront-wool-brigades

- Red Cross Poster 1: https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p16057coll34/id/8

- Red Cross Poster 2: https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/showing-support-great-war-knitting-needles

- Supermodel Kate Moss Wearing A Knitted Union Jack Sweater (Designer Clements Riberio, London Fashion Week, 1997): https://www.pinterest.com/pin/296815431682763800/

- White House Sheep 1: https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/sheep-graze-on-the-white-house-lawn

- White House Sheep 2: https://dcist.com/story/20/03/06/the-white-house-lawn-was-once-covered-with-grazing-sheep

- Wounded American WWI Soldiers Knitting: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/when-knitting-was-a-patriotic-duty-wwi-homefront-wool-brigades

Further Reading:

“A 1920s Fashion History Lesson: Flappers, the Bob, and More Trends That Made the Roaring Twenties Roar.” https://www.vogue.com/article/1920s-fashion-history-lesson

“The best knitwear looks from the 90s.” https://gracielahuam.com/en/diary/the-best-knitwear-looks-from-the-90s

“Exhibition Archives: Knitwear – Chanel to Westwood.” https://fashiontextilemuseumblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/11/exhibition-archives-knitwear-chanel-to-westwood

“Showing support for the Great War with knitting needles.” https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/showing-support-great-war-knitting-needles

“The White House Lawn Was Once Covered With Grazing Sheep.” https://dcist.com/story/20/03/06/the-white-house-lawn-was-once-covered-with-grazing-sheep

“The Wool Brigades of World War I, When Knitting Was a Patriotic Duty.” https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/when-knitting-was-a-patriotic-duty-wwi-homefront-wool-brigades

Leave A Comment