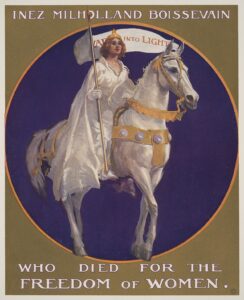

Inez Milholland was born on August 6, 1886, and died less than four months following her 30th birthday. Her life was short but she packed a lot of living into it. Although she didn’t live to see her native New York approve suffrage in 1917 or ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, her contribution to the fight for women’s rights is forever entwined in the women’s suffrage movement in America.

You may recognize her best from the iconic images of her leading a 1913 suffrage parade; majestic in all white riding atop a white horse. This is more about her passionate life.

Early life

Inez was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. Her father, John, was a reporter and editorial writer for the New York Tribune before moving into the pneumatic mail tube business. Pneumatic tubing proved to be a very popular way to move mail around the business center of New York City in the 19th century. This business move afforded the family a life of privilege.

Inez’s parents were socially progressive. John supported many reforms including world peace, civil rights, and women’s suffrage. Her mother, Jean, took Inez and her brother and sister to museums and the theater. She ensured their lives were filled with culture and intellectual stimulation. Regular exercise was also a part of the family’s activities.

Higher Education

Inez’s teen years were spent attending Kensington High School for Girls in London. The graduation certificate was not recognized by Vassar, the college in Poughkeepsie, New York where Inez wanted to attend. She then attended the Willard School for Girls in Berlin so she could earn an acceptable diploma.

Her years at Vassar were full and active. She excelled academically and as an athlete. She participated in a variety of extracurricular activities, too. She was described as an “active and unconventional student, she was always looking for a new or alternative way of going about things.”

Entrance into the suffrage movement

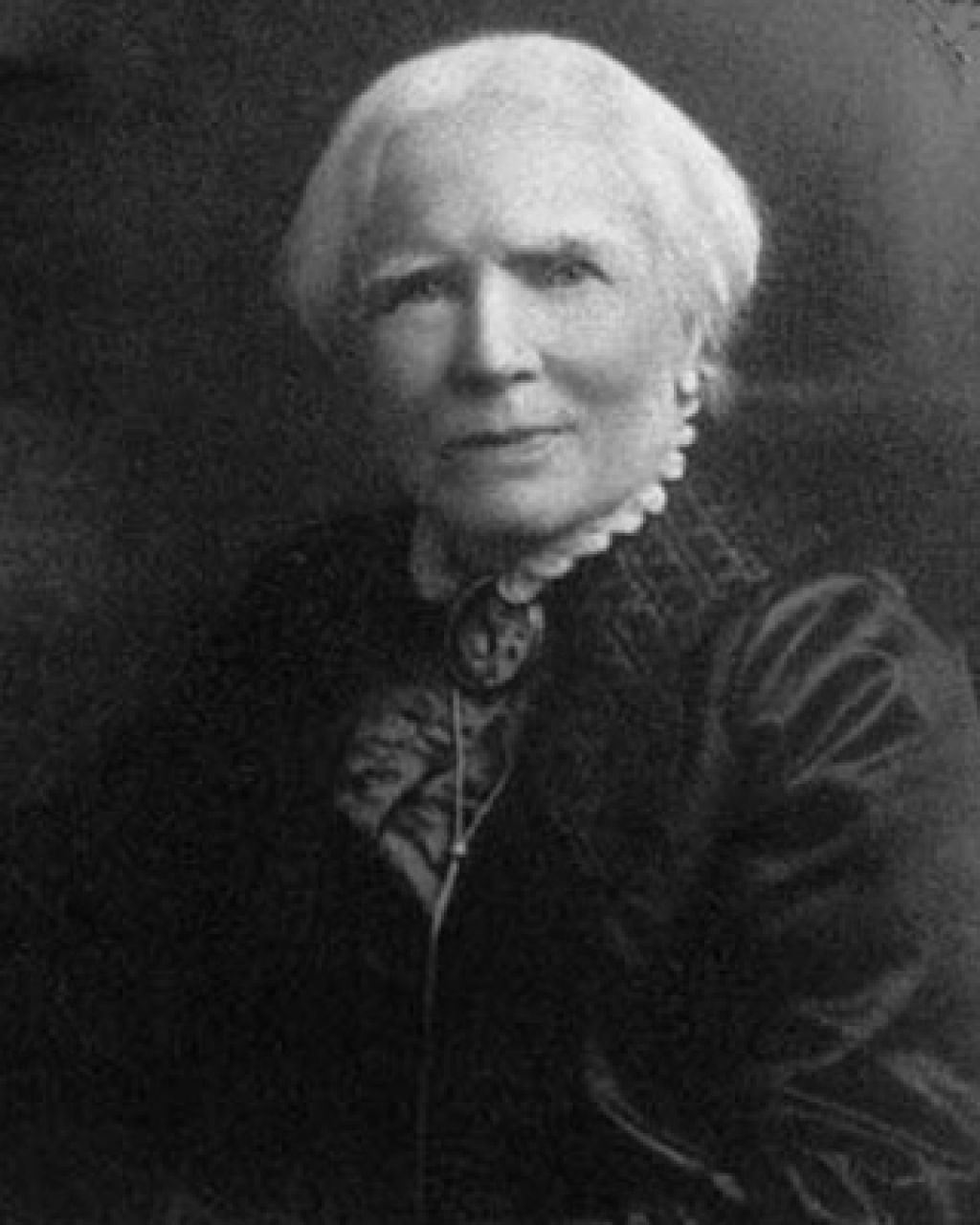

The summer following her sophomore year at Vassar was spent in London. That summer changed Inez’s life was forever. She met and became associated with Emmeline Pankhurst, a leading member of the Women’s Social and Political Union in England. Pankhurst was considered a radical and the WSPU a militant organization. Inez participated in WSPU demonstrations that summer and returned to Vassar with a new perspective that was not welcome by the administration of the college.

The summer following her sophomore year at Vassar was spent in London. That summer changed Inez’s life was forever. She met and became associated with Emmeline Pankhurst, a leading member of the Women’s Social and Political Union in England. Pankhurst was considered a radical and the WSPU a militant organization. Inez participated in WSPU demonstrations that summer and returned to Vassar with a new perspective that was not welcome by the administration of the college.

Inez participated in WSPU demonstrations that summer and returned to Vassar with a new perspective that was not welcome by the administration of the college. She challenged the college’s president who opposed any suffrage activism on campus. Suffrage activities were not allowed on school grounds so Inez invited Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch, to the first meeting of the Vassar Votes for Women club. The meeting took place in a cemetery just off campus.

Inez made her first speaking appearance in support of women’s suffrage following her graduation from Vassar in 1909. With only the aid of a megaphone, she stopped a New York campaign parade for President Taft by speaking from a building window.

She was rejected by Yale, Harvard, and Columbia because she was a woman. But, Inez gained acceptance into the New York University School of Law. She graduated in 1912. Throughout her studies at NYUSL, she continued her work as a suffragist and social activist. She was arrested while participating in the laundry worker strikes in New York City.

Create a suffrage look of your own:

Other progressive activism

After earning her LL.B. degree in 1912 and admittance to the bar, Milholland joined the New York Law firm of Osborne, Lamb, and Garvan. She handled criminal and divorce cases. One of her first assignments was an investigation into the conditions at Sing Sing prison. In addition to prison reform, Inez worked on behalf of word peace and equality for African-Americans. She was also involved with issues surrounding the labor struggles of the Women’s Garment Workers and the Triangle Shirtwaist factory.

Fight for the vote

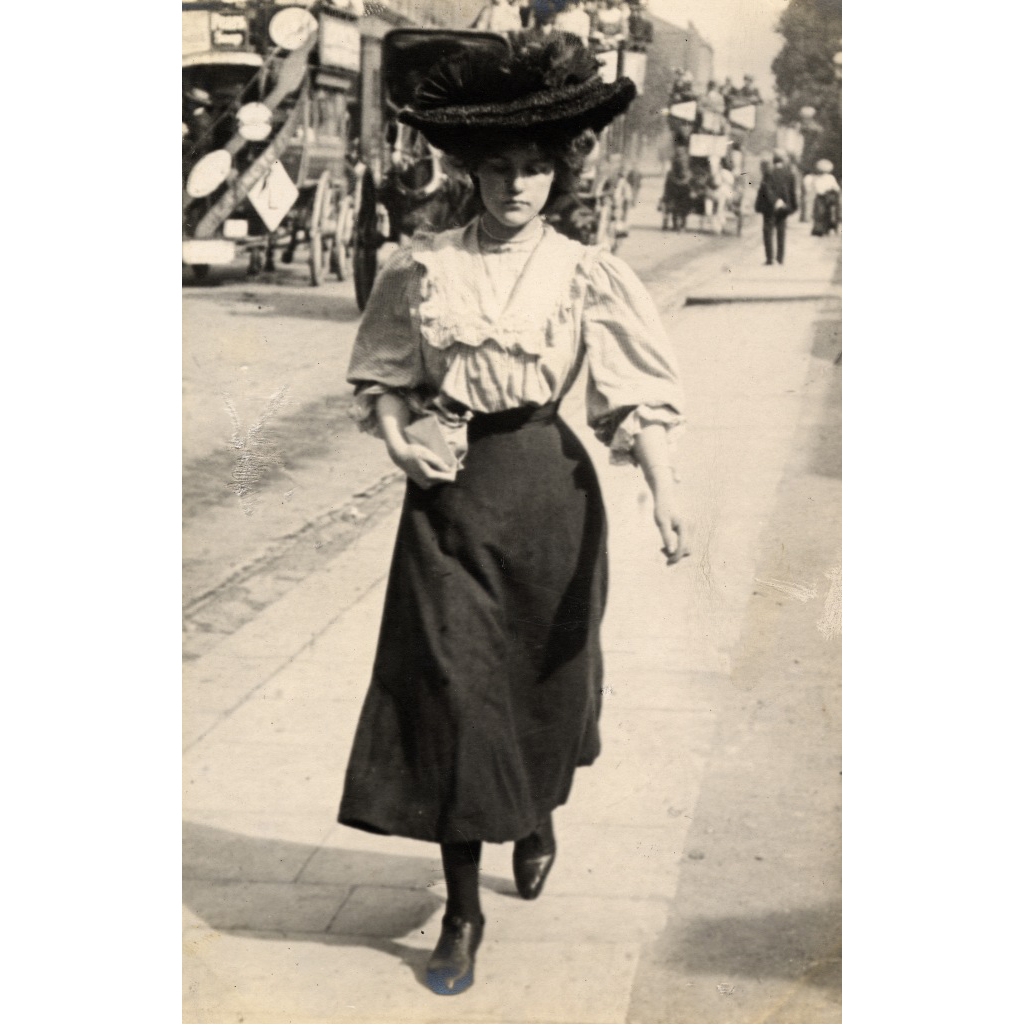

Inez participated in her first suffrage parade in the United States on May 4, 1911. She held a sign that read, “Forward, out of error, / Leave behind the night. / Forward through the darkness, / Forward into light!”

Inez participated in her first suffrage parade in the United States on May 4, 1911. She held a sign that read, “Forward, out of error, / Leave behind the night. / Forward through the darkness, / Forward into light!”

Her most notable public appearance came on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in as President of the United States in 1913. She helped organize the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, DC and led it riding on a white stallion (Gray Dawn) and wearing all white, including a long white cape, and a crown. When drunken men tried to disrupt the parade, she rode her horse into the crowd to subdue them. She made a lasting impression that day!

Milholland believed that women deserved the right to vote because they would metaphorically become the ‘house-cleaners of the nation.’ She believed that women could remove many of the county’s social ills because they were given a voice through their vote.

Fighting to the end

The year 1913 was memorable in more ways than one for Inez. That year, she met and married Eugen Jan Boissevain, a Dutch coffee importer. Their courtship was brief and intense. She is the one who proposed, too! Their marriage was non-traditional, even by today’s standards. They believed in free love. They considered their relationship a “fusion between mind, souls, and bodies.”

The year 1913 was memorable in more ways than one for Inez. That year, she met and married Eugen Jan Boissevain, a Dutch coffee importer. Their courtship was brief and intense. She is the one who proposed, too! Their marriage was non-traditional, even by today’s standards. They believed in free love. They considered their relationship a “fusion between mind, souls, and bodies.”

At the beginning of World War I, Inez worked as a war correspondent for the Tribune in Italy. This allowed her access to the front lines. As a pacifist like her father, she wrote anti-war articles which prompted the Italian government to kick her out.

Inez was beautiful, intelligent, and charismatic. She drew crowds wherever she went. In 1916, she joined a national suffrage tour led by activists from the National Women’s Party. Her health was suffering but she ignored her symptoms until it was too late. An untreated tonsil infection was poisoning her and she finally collapsed at an event in Los Angeles. She never recovered and died on November 25, 1916.

– Donna Klein

More about the women’s suffrage movement

The Colors of Women’s Suffrage

Femininity in Question: Edwardian Depictions of the New Woman

Thanks for finally writing about >Inez Milholland (Boissevain) – Champion of Suffrage – Recollections Blog <Loved it!